News and social media were filled to the brim with talks of mental health sparked by the death of actor Sushant Singh Rajput. Overnight people’s social media handles had analysis, suggestions, self-care tips, and pleas to be reached out when one needs to reach out to others. Many people pointed out for more frequent discussions on the matter and slowly the conversation shifted to other discourses like nepotism and the Bollywood industry. However, when one talks of mental health it is important to remember it is an everyday aspect of our lives.

WHO’s definition of health includes physical, mental and social well being. Mental health is defined as “a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.” Mental health can depend on multiple biological, psychological and social factors and its quality can depend on stressors related to discrimination, exclusion, lifestyles, human right violations, crises and social change. The following will discuss some things we should include in our conversations about mental health like gender, caste, disability, conflict and more.

Gender and Sexuality

June as the Pride Month saw plenty of discussions on gender and sexuality along with the reality of domestic violence and further marginalisation of women and LGBTQ+ folx. Gender and sexuality which play an important role in determining the power dynamics that play out in society result in different possibilities of mental health conditions for people affected by them.

For women, balancing private and public spheres, workplace harassment, violence in the public sphere, responsibilities of childbearing and rearing are just a few issues to name, while in addition to these, trans women struggle with gender dysphoria, lack of rights, hypersexualisation, constant harassment. Men are expected not to express emotions and feelings and are hence less likely to seek help for their struggles with mental health; trans men more so struggle with being identified and included in narratives and discourses of their gender identity. A trans man who is a student in Delhi says, “The gendered checkpoints and washrooms become difficult to navigate as in some instances people feel the need to do a thorough checking and pass comments about my appearance.”

The discussion about gender and sexuality excludes various other gender identities like non-binary, agender, genderqueer and others as most understandings primarily remain within the binary. Same goes for sexuality as stigma outside and inside the community affects people’s comfort to talk about the issues they face and to seek help for it.

Rukmini, a student and activist says, “The discourse around mental health needs to be more inclusive, intersectional, and accessible. When we talk about gender and mental health, we need to understand that historically womxn (referring specifically to white cis heterosexual womxn here who did not even have to deal with the added layers of non-conforming gender, sexuality, or race oppression) were labelled “hysterical” for being depressed, and being visibly trans was (and still is) in itself considered a mental illness, if not criminal. Now we are at an era where the Trans Act’19 in India takes away an individual’s right to self-determination, while conversion therapy continues to take lives. Very few upper caste, upper class, English speaking cis queer folks are able to access affirmative therapy, if at all.”

Ambedkar University Delhi Queer Collective has been a part of promoting fundraises by various individuals such as Grace Banu and Arvind for vulnerable transgender communities in different parts of the country who have been facing the worst of the lockdown’s socio-economic crisis.

For women, balancing private and public spheres, workplace harassment, violence in the public sphere, responsibilities of childbearing and rearing are just a few issues to name, while in addition to these, trans women struggle with gender dysphoria, lack of rights, hypersexualisation, constant harassment. Men are expected not to express emotions and feelings and are hence less likely to seek help for their struggles with mental health; trans men more so struggle with being identified and included in narratives and discourses of their gender identity.

Caste and Casteism

For most upper caste people, caste is the same as reservations. The internet has plenty of jokes and memes underestimating the capabilities of their own batch mates. In addition to their existence in classrooms being debated, most schools and college spaces become alienating to people belonging to historically marginalised castes. The discourse around “merit” invisibilises caste privileges and disadvantages.

For the privileged castes, it is their own hard work and capability, while for the discriminated castes, it is their own personal fallacies. Cultures and opportunities all become defined by caste networks. All the while the casteist slurs are fairly common in daily use. The curriculum created and taught by upper castes generation after generation does not help the cause.

Alaka, talks about generational trauma. “Generation after generation of trauma can lead to someone being predisposed to conditions such as anxiety and depression. Then further experiences with casteism lead to people feeling anxious and depressed and they might seek help for. However, it is not necessary that they might seek help just to cope with the effects of casteism. This could be a contributing reason. Along with this, people also seek help for body image and eating disorders.”

When asked about how accessible help is, she says, “A lot of my friends who have sought help often do not receive the acknowledgement for their issues related to casteism, this makes them feel quite frustrated. Often the therapists are either likely to say that they do not agree with their stances or do not like to talk about this aspect at all.”

Race and Racism

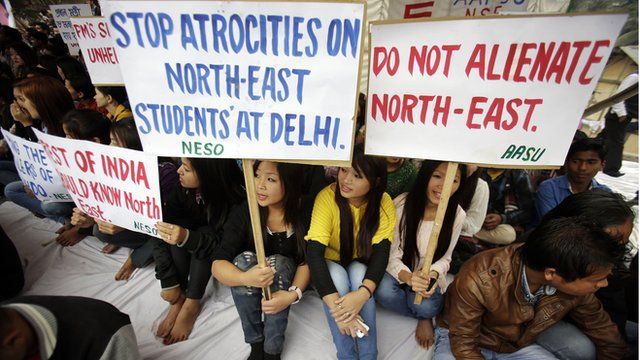

Recently, racism has become an important topic for discussion for two reasons, Black Lives Matter and the coronavirus pandemic. Many have sought attention to be drawn to structural injustices and violence that exist in India when talking about racism in America. Racism in India figures prominently not only with the obsession with fair skin but also othering anyone who look a certain way. The latter is an issue faced often by students from North-Eastern states who become targets of harassment, bullying and violence. With the coronavirus being called the “Chinese virus”, violence has ensued towards people, so racially charged that it does not see them as people of the same country.

Also read: A Racist India & How Its Racism Is Different For North-Eastern Women

However, this is not a new issue. Lalrin Sangi shares her experience of being only nine years old when she had to adapt to a new school environment in Kolkata from her hometown in Mizoram. Not being completely familiar with the basics of Hindi, she recalls the humiliation of being punished for failing her first Hindi exam by being called by her Hindi teacher and being asked to kneel down.

This would happen often until the point where it took her time to not blame the education system back home and her father spoke to the authorities to study Mizo as her second language. She hinted at some institutional discrimination as well. Except for this, she says, “It is quite frustrating to have our accents mocked. Also, stereotypes are a big problem, people think that girls from NE will all indulge in sex work and hence act disrespectfully.”

Economic Status and Inaccessibility

While stigma might make it hard to access help for mental health, money itself a big issue. An hour-long appointment with a therapist might cost you anywhere from Rs. 750 to Rs. 3000, add on to this consultation with psychiatrists, medication, any testing and reports and they cost they might incur. Hence, it is not cheap to have bad mental health. However, mental health might just be the first thing that is affected by one’s economic status. Losing one’s job or not getting one, is the prevalent trend in pandemic which is a huge concern for people’s anxiety and hopelessness.

Despite this, few have talked about the mental health of the daily wage workers, most of them migrants who mapped thousands of kilometres to get back home with few possessions and their families. With no secure source of income for the present and future, no source of the next meal, it is the poor who suffer from anxiety and depression often but lacks the resources for diagnosis and treatment. Add on to this, the fact that poor people are deemed lazy and dependent, and not to forget that lower-class often intersects with caste, gender, sexuality and disability to add layers of oppression.

Conflict and Mental Health Crisis

It is clear to us now, that uncertainty can cause stress and anxiety; this holds true for areas with conflicts and wars as well. Muda, a Kashmiri student discussed how years of trauma and continued violence can lead to anxiety, depression and psychosis. When schools are often shut down, children not only lose out on education but also on memories and experiences they might have otherwise.

It is clear to us now, that uncertainty can cause stress and anxiety; this holds true for areas with conflicts and wars as well. Muda, a Kashmiri student discussed how years of trauma and continued violence can lead to anxiety, depression and psychosis. When schools are often shut down, children not only lose out on education but also on memories and experiences they might have otherwise.

Losing friends and family, gendered violence, death are bound to create a strain on mental health, she says. “I think it wouldn’t be fair to say people here don’t have PTSD because that’s implying that trauma happened in the past while it has been quite continuous for us. It’s things like checkpoints, your family and friends getting injured or killed, losing friends who may be supporting your annihilation. It’s everything contributing to your mental health. I believe over time it gets normalised, you learn to live with it in ways others won’t understand.“

Good mental health must go beyond just the need for survival and hence, this issue becomes important to address. Muda talks about how losing out on experiences and opportunities become routine.

Almost 9 out of 10 people in areas with conflict have the possibility of suffering from conflict-related traumas. Pandemics and conflicts can only further worsen the situation and the mental health of the people in those areas. Radif, a Kashmiri student explains that people not from Kashmir talking about the mental health conditions often do so with no substance and empathy that it often seems demeaning. He further says, “It’s a crisis. There’s one mental health hospital in the entirety of the region. Barely anyone gets help.”

Disability and Ableism

Mudita talks about the importance of language—she recalls how someone once said that her wheelchair is her legs. Years later she says that such notions can be quite alienating and make a person feel they are not fit for the society. “Being different is not a bad thing. People are always different in their capabilities and the things they are good at. What’s bad is feeling that you don’t belong to this world, the world where ableism in the norm. That’s wrong. That begins with the way we use our words.” She says that her friends now say let’s go, we can walk and you can roll (the wheels of her wheelchair).

She talks about instances that come from ableist perspectives which are often exclusionary that have stayed with her for a long time. Public spaces are not often accessible and the onus of the accessibility is on those who feel excluded, she discusses. She questions, “Why should I always adjust? Just because I’m the disabled person?”

In terms of accessibility for mental health, while some hospitals and clinics are wheelchair accessible, it can’t be said the same for all people with disabilities; Mudita says and believes therapy should be more accessible in terms of literature in braille and sign language interpreters. “At the same time, people should not assume people with disabilities go to therapy just for solely disability-related issues, they could be going to therapy for any reason at all. We should not reduce people to their disabilities and at the same time, we should make their lives into inspiration porn. You should look at them as any other human being and treat them the same.”

Religion and Discrimination

Mental health is related to everyday things like changing one’s vocabulary and carrying vegetarian food for lunch to be included. Afreen talks about the lack of real representation of her community, which was often just an idealistic chapter on Eid. Such everyday things become quite alienating because either you become a subject of interest or are not cared for at all.

However, this is just from her childhood; she discusses now her niece and nephew are called out indirectly being terrorists and are highly disturbed by this. Things get normalised, Afreen discusses. Islamophobia shows itself in questions like, “Pakistan lost the match, why are you so happy?” Now that she’s become more politically aware and speaks out, people often infantilise her for overreacting, saying that she’s too sensitive.

Also read: The War At Muslim Doorsteps: Voices That Were Left Unheard

What to Keep in Mind

To understand how these things operate and come into effect, Dr. Shivani Nag, Assistant Professor in School of Education Studies, Ambedkar University, Delhi was asked for her expertise as her research focuses on socio-cultural inclusion, experience and participation of the marginalised in education. She discusses that when we talk about mental health, we need to consider both personal and institutional reasons.

On a personal level, suppressing aspects of oneself that get backlash from one’s community and society can cause anxiety. Often things work at both levels. Structurally and institutionally, one could feel powerless due to the power dynamic and feel so hopeless that they give up fighting against the system. In environments which are ridden by conflicts and uncertainty, it could again cause an intense amount of stress. The prolonged experiences of stressors could turn into various kinds of mental health conditions. She suggests that it is important to be informed and considerate about mental health. Empathy must be inculcated from the very start rather than waiting for someone to reach a breaking point.

References

Featured Image Source: UNC Health Talk

About the author(s)

A spoken word poet, writer and a graphic design enthusiast, studying education. Passionate about a wide range of things, anywhere from political theory to queer representation to artificial intelligence.