Historian Nicolaus Mills coined the term “a culture of humiliation”, perhaps the most comprehensive one to describe Bollywood’s much layered existence, where caste and class intersect to influence how a subcontinent of over 1.3 billion people consumes art and fuels an entire affiliate industry of news and infotainment.

As with life outside the golden gates of Bollywood, individuals within are reduced to their commercial selves caught between the binaries of profit and loss, risk and crisis management, mergers and acquisitions. Where the biggest annual releases are earmarked for the Khans, Christmas for Aamir, Diwali for Shah Rukh and Salman for Eid. The fear of being drowned out by them so palpable that no filmmaker in their right mind would consider releasing their films on these red letter dates.

The Bollywood box office then is the single biggest factor to make or break lesser mortals like Sushant Singh Rajput. This is an ecosystem where one is only as good as their last film and where the only acceptable zero comes in a clothing size.

The Bollywood box office then is the single biggest factor to make or break lesser mortals like Sushant Singh Rajput. This is an ecosystem where one is only as good as their last film and where the only acceptable zero comes in a clothing size.

Also read: Sushant Singh Rajput And The ‘Justice’ That The Media-Court Promises

Within this culture of humiliation, exist Bollywood’s gatekeepers; the male heads of feudal families who come from the heteronormative north Indian patriarchal culture of musket and moustache. Bollywood’s power brokers, are not unlike mob families–in that Godfathers have their turfs and rely on omerta to protect its stakeholders. To retire as head of a family run production house like Yashraj Films, Balaji Telefilms, Rajshri Films and Dharma Productions is every actors’ ultimate goal. This is where only a privileged few can afford the luxury of failure.

In fact, the very definition of the hero in Bollywood is in keeping with literary definition. That he be high born enough so his misfortune and death be suitably termed tragic. This means documenting the lives of savarna and cis. Making it an aspirational one for the millions who watch these films. It’s impact underlined by writer Maya Angelou, “People live in direct relation to the heroes and sheroes they have.”

The continued opportunity to younger clan members of Bollywood’s first family is possible because of this legacy and their pre-Partition status as landed gentry. The list of Punjabis and Pathans who dominate the landscape is endless. Rajesh Khanna, Guru Dutt, Sunil Dutt, Dilip Kumar, to Shah Rukh Khan, Akshay Kumar, Ranbir Kapoor, Ranveer Kapoor.

With each new entrant gaining a foothold in the industry, more came from the “pind” or village, secure in the knowledge that work would be provided by his country cousins. A system of references and checks which has stayed under the control of post-Partition migrants to Bombay.

Six degrees of separation has consolidated power and bred a monoculture of sorts resulting in cinematic mediocrity; in the confused and poorly comprehended portrayal of subjects outside the thickly insulated glass of its fish bowl.

When questioned about the monopoly and nepotism of film families of Bollywood, actor Saif Ali Khan said offspring of erstwhile actors acquire the “genetics and eugenics” validating preferred treatment – this is similar to the oft repeated upper caste argument that the monopoly they occupy in all spheres of life is the product of ‘merit’ not privilege. This misconception contributes to the fact that despite being the largest film industry in the world, valued at nearly 185 billion dollars it has managed the grand total of three Oscar nominations in a hundred year arc of its existence.

The Hindi film industry’s output showcases this reductive gaze onscreen, one which reduces entire regional cultures, ethnicities, religious and sexual minorities to caricatures and perversions; the Nepali gurkha, slow on the uptake, the drunkard Christian with the easy daughter, the hyperbolic Sardarji living life Singh size, the beatific Muslim best friend, whose “dosti” never gets legitimised into “rishtedaari”.

Between this caricaturing, the best a Dalit character can hope for is to be a catalyst to the Brahmin hero. Dalit characterisation is contextualised by the savarna lens which does not cede a middle ground in its depiction of Dalit characters, veering between invisibility or hypervisibility of the dirty and desperate, measured in terms of their savarna aspirations to cleanliness and therefore, godliness.

It is to this world the small town newcomer comes, wanting to be the next SRK. And while they may belong to an upper caste like Sushant Singh Rajput, who also shared the TV-to-film transition with Khan, that’s where the similarity ends. Instead, what awaits most outsiders is shame and ridicule in the Dinner for Shmucks show format of Koffee with Karan.

The isolation and lack of a strong support system makes outsiders more vulnerable. Unlike star kids who have a legacy of advice on how to navigate brutal failures, the newcomer has no such intellectual wealth to tap into. Rejections and box office failures could prove lethal. Often the fear of losing out on work and being outed for seeking professional help for mental health concerns keeps performers under severe stress and self medication.

World averages show far more men than women will die from suicide as a result of mental illness because patriarchal culture tells men the lie that admitting to any sort of emotional pain is ‘weak’ and ‘not manly’. Abysmally low awareness levels of mental health concerns and its deep stigmatisation means society perpetuates age old socio-cultural and religious prejudices as a means of making sense of what they do not understand collectively. Like when AIDS was referred to as “gay cancer”, and while science was still figuring out its genesis, society’s pre-existing homophobia resulted in gay men being blamed for its outbreak and spread.

It is not hard to imagine the psychological and cultural obstacles posed to those already struggling, where the management of mental health concerns through a daily regimen of therapy and medication, becomes virtually impossible; often leading people with depression to adopt alternative and under researched methods such as the use of cannabis to manage their feelings of anxiety, stress, depression and suicidal ideation.

A study conducted by leading medical journal, The Lancet, has shown the potential risks associated with the use of cannabis. The process of finding the right medication to treat psychiatric illness even under a professional often involves a difficult period of trial and error, and a further period of adjusting dosages to find the optimal therapeutic level. While it is a matter of medical integrity that psychiatrists should highlight the dangerous consequences of irregular medication, abrupt discontinuation and taking a cocktail of medication and other substances, the decision making unfortunately lies in the hands of the patient.

Toxic masculinity has flourished in the antics of so called “bad boys of Bollywood”. Offscreen, Sanjay Dutt, Salman Khan, Saif Ali Khan were the forerunners of this dubious moniker. Onscreen, the arc of violent men continues from Bachchan’s angry young man of the 70s, Dutt’s Khalnayak of the 90s & Shahid Kapoor’s Kabir Singh. Sholay to Gangs of Wasseypur glamorising the provincial, caste ridden world of small town India.

Bollywood is no place for those who do not reinforce gender binaries, forcing even well known filmmakers who enjoy an immense degree of clout in the industry to stay inside the closet. According to gender theorist Judith Butler, “That gender reality is created through sustained social performances means that the very notions of an essential sex and a true or abiding masculinity or femininity are also constituted as part of the strategy that conceals gender’s performative character and the performative possibilities for proliferating gender configurations outside the restricting frames of masculinist domination and compulsory heterosexuality.”

Against this mise en scene there are softer masculinities portrayed by Rajkumar Rao, Vikrant Massey, Ishaan Khattar, Ayushmann Khurrana and Rajput. Rajput’s “adarsh balak” image is that of millions of boys on whose shoulders pivot the family’s hopes and desires. A world where one is told the half truth that hard work pays; one that obscures the fact that networks of privilege and caste affiliations take you further. His agency and changing priorities are denied, and he always remains the little boy led astray by the calculative big city woman and gold digger. The girlfriend is seen as an illegitimate female companion, vilified and blamed for anything that goes wrong in the life of the son. It becomes much easier therefore, to accuse a son’s girlfriend of black magic instead of admitting he could be gravely mentally ill.

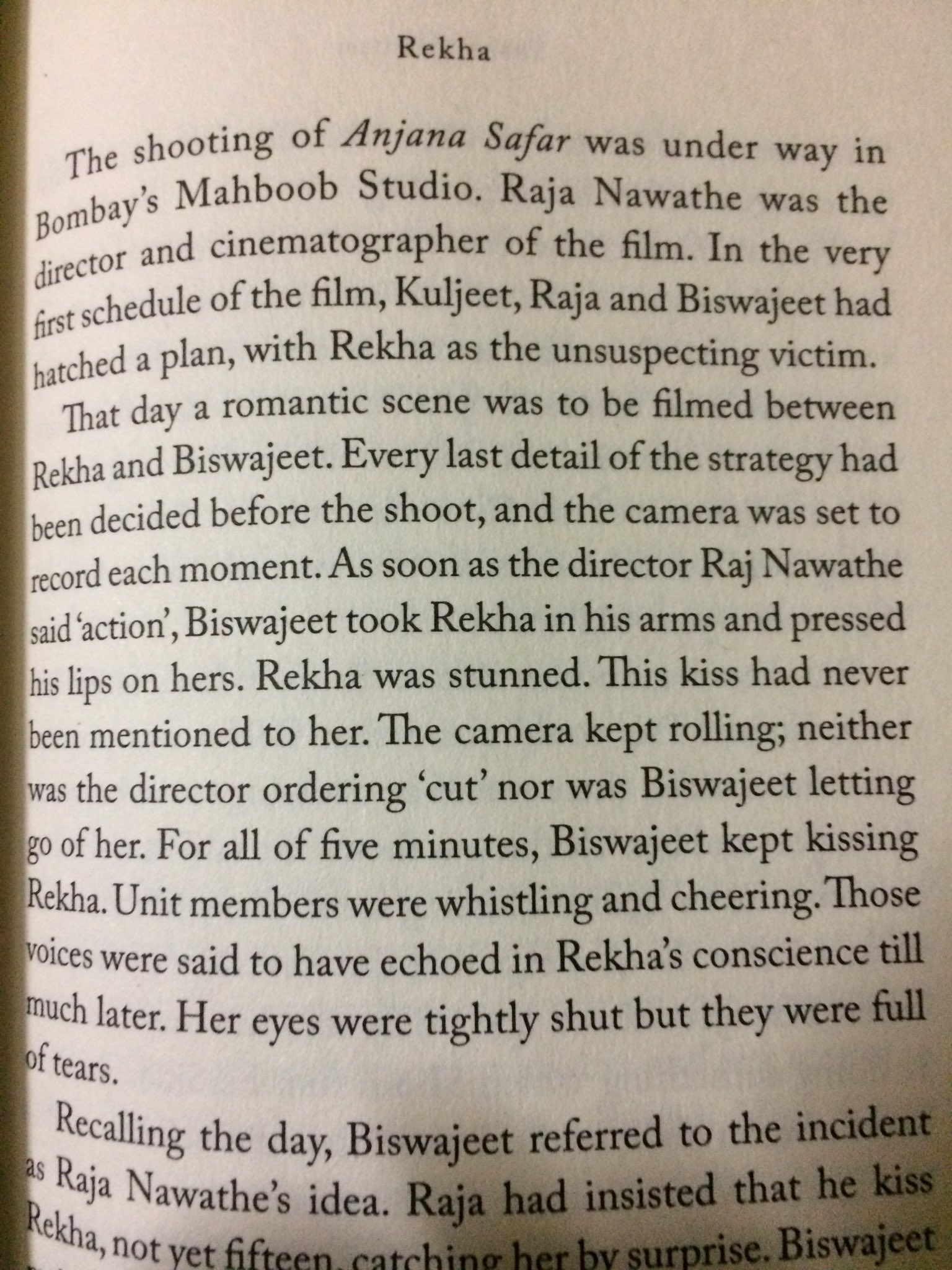

A few decades back, before television news became a nightly trial by media, Rekha was called a “dayan” by her former mother in law. In another incident, actor Vinod Mehra’s mother allegedly attacked her with her slipper for having married her son in secret. The story of a teenaged Rekha being forcibly kissed by her much older co-star, Biswajeet, on the sets of ‘Anjana Safar’, is one of the few metoo stories of that era that made it to the pages of film journalist Yasser Usman’s book, Rekha: The Untold Story.

Rhea Chakraborty’s witch hunt and trial by media is an extension of the kangaroo courts in housing societies where the middle class pass sentences on ‘wayward women’ who have acquired agency after getting an education, a job, hobbies and a life beyond the surveillance of gated communities and immediate family. These days the online trolling from fans of actors has put in sharp relief the levels of abuse even famous women are subjected to. The question that follows is, what then of the ones who do not have the same caste and class privileges?

While all female experience is violent, the most oppressed bear the worst of it. Dalit women have been shown by a United Nations study to live nearly 15 years lesser than women from upper castes – “due to the intersection of gender-based oppression with other forms of discrimination of caste, race/ethnicity and religion, disadvantaged in their access to quality education, decent work, health and well-being.”

Also read: Is Bollywood Really Ready To #SmashPatriarchy?

Monika Lewinsky says the culture of humiliation “not only encourages and revels in Schadenfreude but also rewards those who humiliate others, from the ranks of the paparazzi to the gossip bloggers, the late-night comedians, and the Web “entrepreneurs” who profit from clandestine videos.” What happens when news is required to entertain.

A sad reminder of the fact that Silk Smitha too died by suicide, a note in Telegu stating that repeated failures in life was the reason behind her taking the extreme step. How many more will be the collateral damage to this culture of humiliation?

Nothing states the sordid truth like Vidya Balan’s character Silk Smitha in The Dirty Picture, “Jab sharafat ke kapde utarte hai … tab sabse zyada mazaa sharifon ko hi aata hai.” A sad reminder of the fact that she too died by suicide, a note in Telegu stating that repeated failures in life was the reason behind her taking the extreme step. How many more will be the collateral damage to this culture of humiliation?

Nina Sangma is an independent journalist and strategic communications consultant. She has worked in corporate media in various roles and mediums including television, digital, and radio. Her writing focusses on film, culture, gender, labour, and the impact of technology.

Jolene Fernandes is an anti-caste activist, mental health advocate, and Masters in Sociology with a focus on caste, gender, culture, and development.