By narrating stories of evil he desires to highlight the good, not the evil. He is not narrating lust for lust, coercion for coercion, oppression for oppression, sin for sin; but to evoke a deeper understanding of the hidden agenda of a hypocritical society.

Dr Arfa Sayeda Zehra, ‘Manto: The unmatched craftsman who strips life of its illusions’

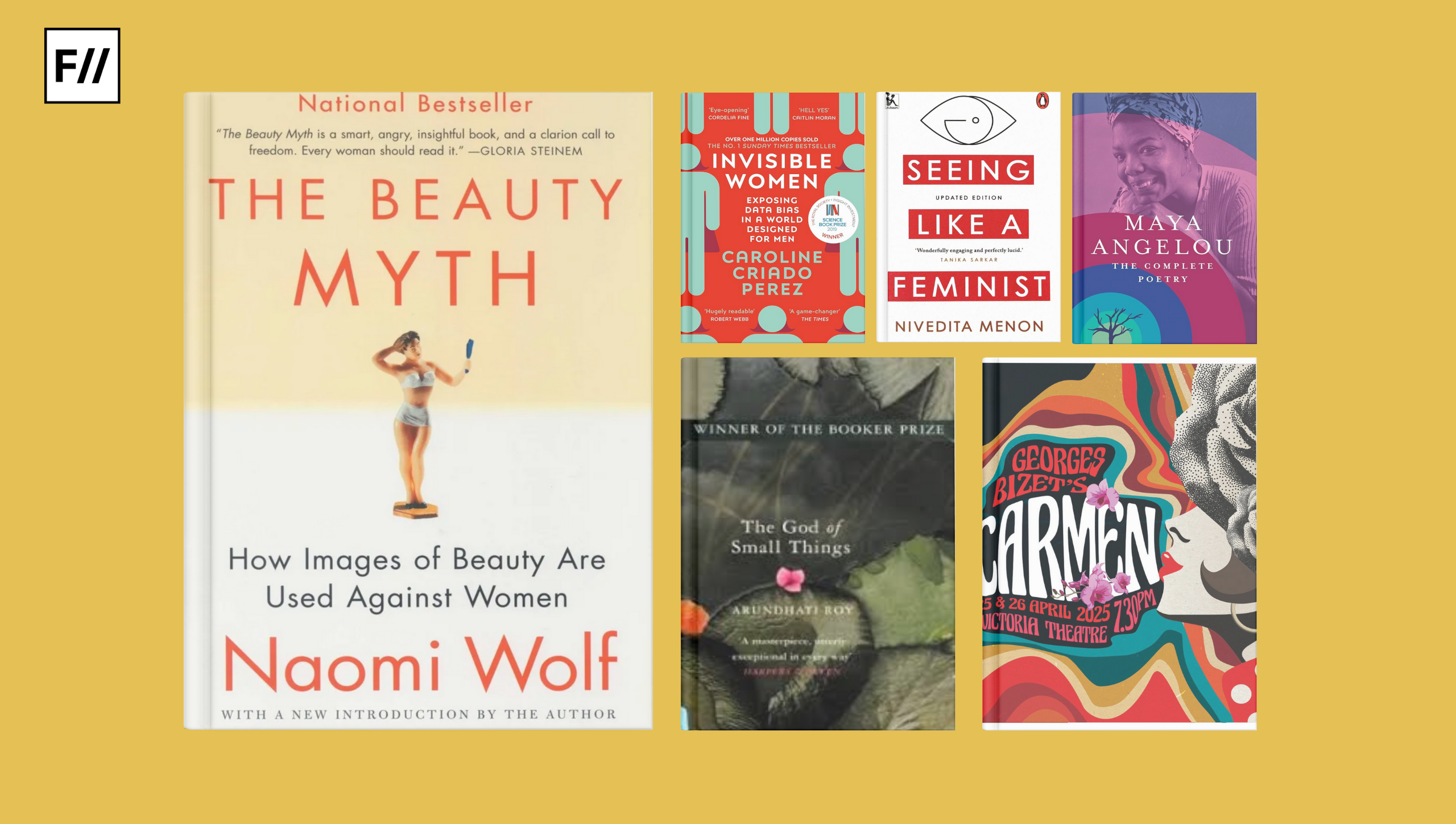

The unraveling of women in Manto’s short stories remains akin to awe. Manto’s penning down of women is free from the bald fabrication of toxic tangles of plastic bodies, slim waists, colour cards and absurd adhesive brand endorsements. Women in Manto’s world are not exotic showpieces, neither constructs of fantasy; but simply put—humans.

Manto’s pen doesn’t cater to similes, metaphors, alliterations and imagery. His pen blatantly spits facts. Facts that must be spoken; spoken fast; spoken without ornamentation. Perhaps, this is what transitioned his ink as a mere blot as court hearings became a part of his writing:

No sensitive man, and I consider myself one, could have gone through the experience unscarred. A court is a place where every humiliation is inflicted, and where it must be suffered in silence.

Manto in his piece, ‘My Fifth Trial (Part I)’

One can reason out that it is Manto’s mind that does not allow him to delve into stylized orientation. The pain of Partition engulfs him as he comes across killings and atrocities in the name of religion:

Every morning’s paper is filled with details of cruel acts. What’s behind all this? Should we lose faith in humanity? Why have we suddenly become so bloodthirsty?

‘News of a Killing’ by Manto

His mind is troubled, hence elaborate exaggerations and extensive imageries only exist as a utopian privilege. Manto does not romanticize female entities; he does not fasten corsets, but lets them breathe. The clearest example of his writing style reflects in Bu, the odor of a woman is described as rather peculiar, than pleasing or enchanting. It is enigmatically uncanny, not supposedly exquisite.

There is a unique weaving of women characters that separates the ‘man’ from human, it makes you question what slips out of naked eyes, it makes you interrogate the ‘men will be men’ rhetoric and transitions it into one echoing question, “Will men ever cease to be men?“

Also read: Manto And His Revolutionary Writing: Thanda Gosht Review

An innocent Saugandhi in Hattak is seen to be in want of the warmth of comfort and affection, however, what she receives is objectification at the hands of the man in the motor and exploitation at the hands of the oppressors. As Saugandhi’s eyes are blinded by the flash of immense light, readers take off the blindfold of inhuman objectification. As Saugandhi’s entity is reduced to a source of pennies, society’s failure is highlighted. Lastly, when Saugandhi seems to find companionship in a dog, we seem to ask a solitary question, “Was a dog able to furnish what society failed to provide?“

Manto asks us questions through Saugandhi, the answers to which are known; but unspoken.

When pages are turned to Manto’s Do Kwamein, Sharda awaits us with a question. Manto makes one rethink about the perceived idea of romance that has lurking underpinnings of society’s hierarchy as Mukhtar’s supposedly ‘justified’ actions overlook consent. A story that commences as an act of unsolicited agency of man, masked with innocence; fades with the unmasking of unsolicited agency of man. Manto makes Sharda ask a simple question, the answer to which remains deafening silence.

Also read: Manto’s Mirror To Partition: A Feminist Review Of ‘Khol Do’

Khol Do stands as another gut wrenching story that is unfortunately a truth to many. As Sakeena lives through unfathomable deaths on the bed, an unsettling thought runs through the spine. Manto, through Sakeena, shows the ultimate truth of the perpetrators who roam around freely as the glorified protectors. The worst part about this truth is its overarching expansion that goes beyond all spatial and temporal boundaries. Beads of perspiration trickle down the forehead as realization dawns upon readers – Sakeena is not fictional; but a contemporary reality.

From strengthening vulnerability surfaced in Sadak Ke Kinaare, to Neeti’s latent vulnerability under immense strength in Licence; Manto emphasizes on the failure of the society that repeatedly silences women to the brink of shattering. There is absence in autonomy, from body to fuel of the body – the rightful ownership that women deserve is transcended as mere possessions of the society.

Neeti, Sharda, Sakeena, Saugandhi, the names keep getting added. They are not confirmed to hardcovers or history; they continue to live as truths of present. Feet march in pace past dusk, lips are still sealed, female bodies remain as sites of violence, and patriarchy remains an overarching evil. As the clock ‘progressively’ shifts from the twentieth century to the twenty-first century and fences of partition are replaced by sky scrapers and metropolitans – the reduction of female entities and possession of female bodies continue as living through contemporary, dystopian non-fiction.

Manto’s rhetoric refuses to be transient:

Woh toh khudko nahi bechti, Lekin log chupke chupke usse khareed rahe hai! (She does not sell herself, but people stealthily buy her)

Licence by Manto

Also read: Why Manto Continues To Be Relevant Today

Priyanshi is often seen scribbing on the last page of random notebooks, nodding her head in disapproval. This overthinker is a student from Lady Shri Ram College for Women. She can be found on Instagram and LinkedIn.

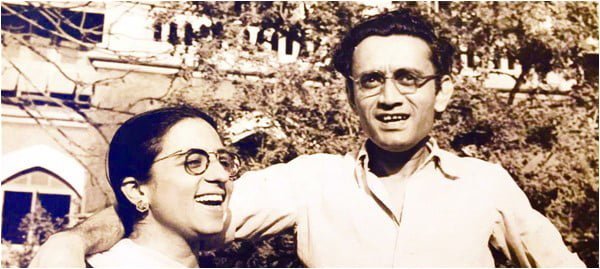

Featured Image Source: Bqrnd.com

Every bit of it is so true.