Sexual violence should not happen to anyone. But unfortunately, it does. And what follows could leave the survivors feeling vulnerable and confused. Their interaction with the criminal justice system is often difficult, especially because traditionally the system envisages a role for the state and the defence, but not really for the survivor. Often, a lack of information about legal precautions that ought to be taken, results in the loss of important evidence, or the weakening of the case. We are, however, slowly moving towards a survivor-centric approach, and it is important that the survivor is empowered through information about the system she will have to interact with. This article aims at giving a lawyer’s perspective on some things the friends and family members of the survivor or the survivor herself should keep in mind, in case of sexual violence, in order for a proper prosecution of the case.

In the immediate aftermath

The safety of the survivor is a priority in the immediate aftermath of rape, and she should reach a safe spot as soon as possible, if necessary with the help of family or friends or the police. The reporting of the crime should be done right-away, to preserve the integrity of the evidence and to record the statement of the survivor when the chain of events is fresh in her mind. Although a delay in registering the FIR (first information report) can be explained at a later stage, it is always advisable to report the rape immediately. The police are under an obligation to lodge the FIR in rape cases, and refusing to do so will make them liable under Section 166A of the Indian Penal Code. The survivor should ask for a copy of the FIR.

If sexual assault takes place, the first instinct of the survivor or her family very often is to ensure that she takes a bath and changes her clothes. This is a very bad idea. A bath is very likely to wash out important forensic evidence, and it is very important that all physical evidence of the rape should be preserved. Hence, until a medical examination is conducted, the area where the assault took place should not be disturbed, and the clothes worn at the time of the assault should not be changed. If the survivor does decide to change the clothes worn at the time of the assault, they should be preserved in paper bags (not plastic bags) and submitted during the medical examination.

The survivor of rape is also entitled to free medical treatment/first aid at all hospitals, whether they are public or private, and not doing so makes the hospital in-charge liable to punishment under Section 166B of the Indian Penal Code (for a term that may extend to one year or fine or both). The Medical Examination (MLC) of the survivor of rape, for the purposes of the investigation, has to be done by a registered medical practitioner (RMP), if possible an RMP working in a hospital run by government or by a local body, and this has to be done with her consent. The medical examination has to be done within 24 hours of receiving information about the commission of the offence, as provided in Section 164A of the Code of Criminal Procedure. It is imperative that the survivor asks for a copy of the medical report. Neither the police nor the Magistrate are entitled to touch the survivor, or ask for a visual examination of her private parts. This can only be done by the Registered Medical Practitioner.

The two-finger test

Every survivor should be aware of the controversial ‘two-finger’ test. In cases of sexual assault, some doctors insert fingers into the vagina of the survivor to see whether it admits two fingers or one. The objective of the test is to see whether the survivor is ‘habituated to sexual intercourse’. The Supreme Court of India has categorically stated that

“the two finger test and its interpretation violates the right of rape survivors to privacy, physical and mental integrity and dignity. Thus, this test, even if the report is affirmative, cannot ipso facto, be given rise to presumption of consent.” (See Lillu@ Rajesh v. State of Haryana, Supreme Court of India).

The guidelines of the Department of Health Research on Forensic Medical Care for Victims of Sexual Assault released in 2013 makes it abundantly clear that the two-finger test is degrading and also, medically and scientifically irrelevant. Hence, the survivor should not be subjected to a two-finger test, and has the right to refuse it.

Statements to be made by the survivor after the registration of the complaint

After an FIR is registered, the survivor has to give a statement known as the ‘161 statement’ (this is provided for under Section 161 of the Code of Criminal Procedure). This is a statement made to the police, which is reduced into writing by them, and these statements are not to be signed. One needs to keep in mind that this statement should be taken down in the language of the survivor, and the survivor and her family/friends should ensure that words are not put in her mouth. This is important because, the consistency of the 161 statement with other statements (the 164 statement and testimony of the survivor), is an important factor in lending credibility to the case. Naturally, the statements should be recorded in her own words, to avoid subsequent inconsistencies.

Another statement that the survivor needs to make, is the ‘164 Statement’, which is recorded before a magistrate (and provided for in Section 164 of the Code of Criminal Procedure). The Supreme Court of India has issued guidelines in a judgment (See State of Karnataka by Novinakere Police v. Shivanna), where it has held that on learning of the commission of the offence of rape, the Investigating Officer is supposed to take immediate steps to take the survivor to the nearest magistrate (preferably a female magistrate) for the recording of her statement. If there is a delay of more than 24 hours in the recording of the statement, the investigating officer is supposed to record the reasons for this in his case diary.

It is very important that the survivor explains clearly and cogently what happened to her. Given the traumatic nature of the experience, and the fact that women may face cultural barriers in speaking about sexual violence, it may be understandable that the survivor wishes to be reticent about the details of the incident. This can, however, have serious repercussions for the successful prosecution of the case. For example, a lot of survivors refer to the sexual assault as ‘Galat kaam’ (wrong act). However, while making their statements it is necessary to elaborate on what one means by ‘Galat Kaam’, since it is a broad phrase that can have different connotations depending on the context. It is the responsibility of the stake-holders in the criminal justice system to ensure that the survivor is made aware of the need to make a clear and cogent statement, and is comfortable enough to do so.

During the course of the trial, the survivor will also have to testify about the incident. This testimony will be taken in an in-camera proceeding, and will include an examination in chief (done by the State) and a cross examination (done by the defence) in the presence of the accused. It is important that the survivor speaks clearly, cogently and confidently during these proceedings, and does not nod or shake her head in answer to the questions, to indicate a yes or no. The survivor has a right not to be asked scandalous or indecent questions, and the Court may forbid the asking of such questions, if they have no relation to the facts in issue or are not necessary.

The survivor’s right to privacy

The law has certain provisions that protect a survivor’s right to privacy. ‘Section 228 A’ of the Indian Penal Code makes the disclosure of the identity of a rape survivor an offence that may be punished with up to two years of imprisonment. This includes making any such information public that may lead to the disclosure of the identity of the survivor. An example of this would be a hypothetical newspaper report that reveals the street on which the survivor lives, and the name of her parents. This information is potentially sufficient to lead to the disclosure of the identity of the survivor and is punishable under this Section.

Further, the survivor is entitled to an ‘in-camera trial’, which means that the public will not have access to the proceedings. This is usually done by asking members of the public to leave the Court room, and allow the testimony of the survivor to happen only in the presence of her lawyers, the Prosecutor, the Judge, the accused and his lawyer and the necessary court staff. This is done to allow the survivor to speak freely about the incident. The Supreme Court of India has issued guidelines in a 1996 judgment, on the conduct of these trials and placed a responsibility on the judges, to conduct the proceedings with utmost sensitivity and not allow the cross examination to be an opportunity for the harassment of the survivor. Certain courts in Delhi also have what are called ‘Vulnerable Witness Rooms’ where witnesses can depose without having to face the accused.

The survivor is entitled to a lawyer

The law entitles the survivor to a lawyer, even though the lawyer has to Act under the direction of the public prosecutor. If the survivor cannot afford a lawyer, she may request the Court to make legal aid available to her. She is entitled to legal assistance at every stage of the proceedings, ideally right at the police station itself. In guidelines laid down in Delhi Domestic Working Women’s Forum v. Union of India it has been stipulated that complainants of sexual assault should be provided with lawyers, and that it would be the duty of the police to inform the survivor of her right to legal representation before any questions are asked to her.

The rates of conviction in rape cases in India continue to remain low. The causes for this are manifold including structural and social disadvantages, as well as problems in our legal system. Recent events have created a momentum for protecting the rights of the survivor, but much of it has been directed towards groups demanding stricter punishments for the perpetrator. Not enough attention is given to the rights of the survivor, in their own interaction with the justice system. Civil society needs to put pressure on the legal system to ensure that survivors do not feel re-traumatized in the course of the trial of their perpetrator. The prosecution of a rape case should not become a second ordeal for the survivor. The real achievement in survivor’s rights will come when the difficult process of the trial, is made a little bit easier, and a little more sensitive to the needs of the survivor. Educating her of her entitlements and some precautions is a small step in that direction.

Author’s Note:

i. This article begins with the caveat that it is written from the Indian perspective, keeping the Indian reality in mind. The intention of the article is not to make survivors of violence feel guilty or responsible for any loss of evidence, but rather, to empower them by making them aware of legal provisions and procedures. Lastly, though this article refers to survivors as female it fully acknowledges that men and boys too can be survivors of sexual violence, and that the Indian law on rape is deficient in reflecting the concerns of adult male survivors of rape (though the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 covers boys in its ambit). This article is particularly about adult women survivors of rape (though a lot of it is applicable to children as well), and if the reader wants to know more about the POCSO Act, they can do so here.

ii. Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code defines rape, which has been made much broader after the Criminal Law (Amendment Act) of 2013. Now, this definition not only includes penal-vaginal penetration, but the penetration of the anus or vagina with the penis, fingers or any other object, as well as forced oral sex. The focus of this article is, however, not on the substantive law of rape, but on empowering the survivor to effectively navigate the criminal justice system.

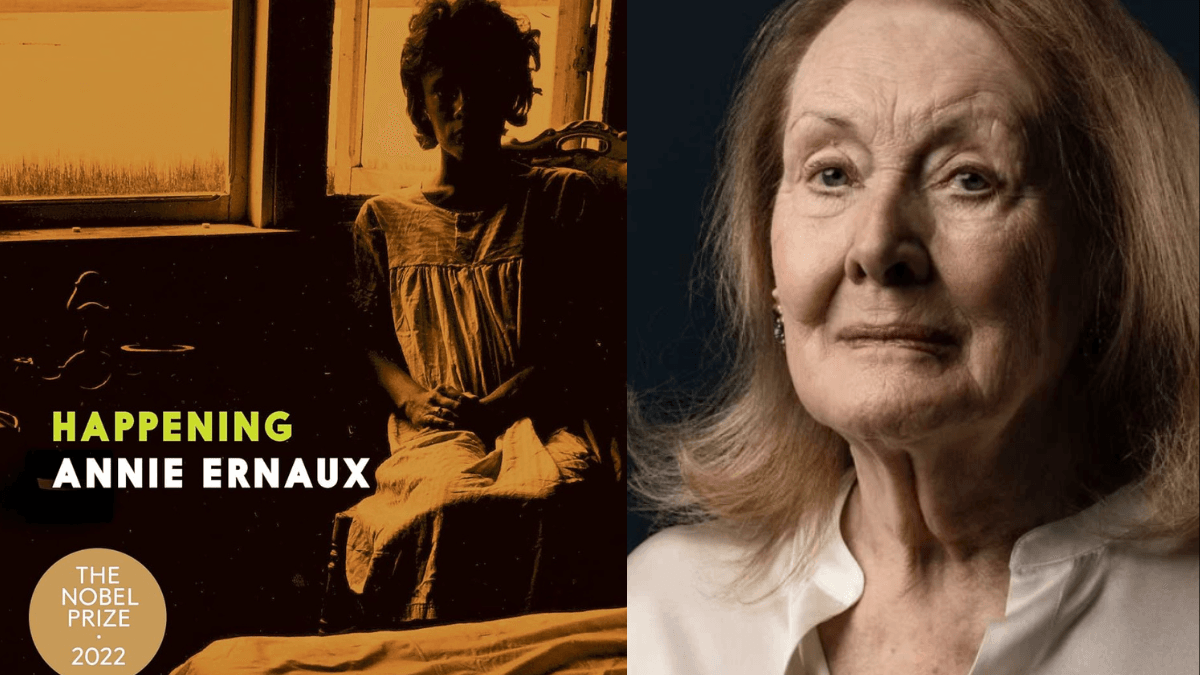

Featured Image Credit: Indian Country Today Media Network