India is a country with more cultural, religious, and lingual diversity than any other country in the world. It is also a land of Hindu upper-caste dominance and privilege. People like me, who belong to these upper-castes are blissfully unaware that there has been, over centuries, a cultural homogenization which works in our favor, and against the people of other castes and religions. The rampant spread of right-wing Hindu nationalism has only compounded this. The primary unit and the most basic tool that brings about this homogenization is the Hindu family, which is based on an upper-caste patriarchal North Indian norm.

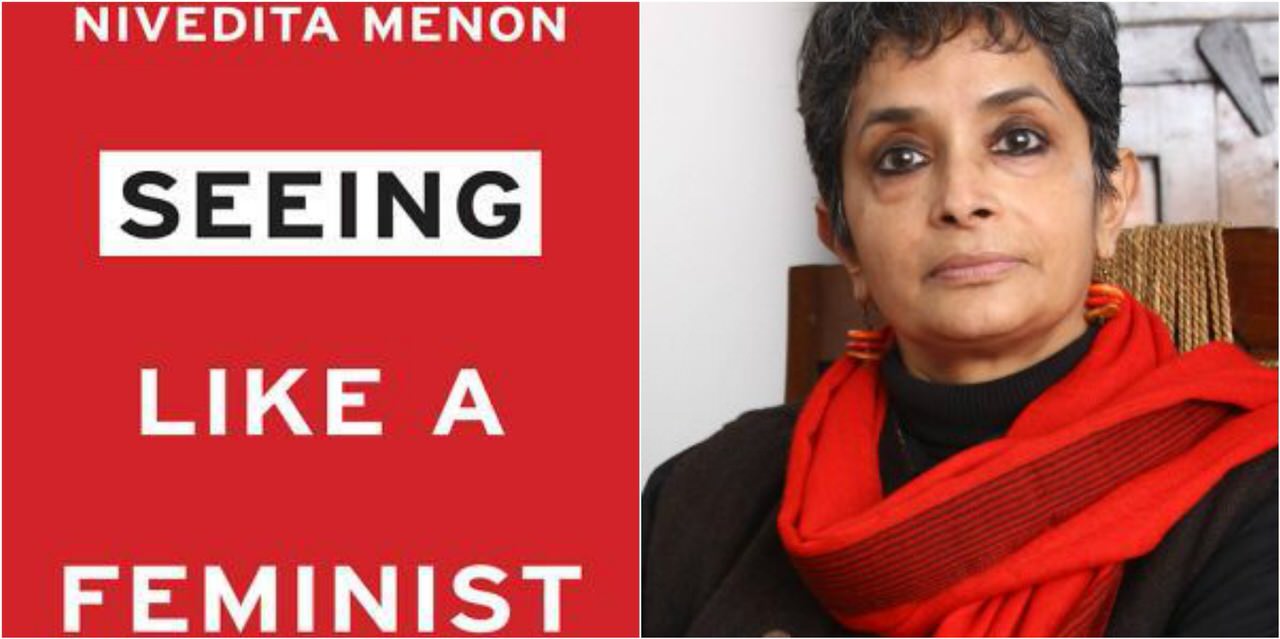

Book: Seeing Like A Feminist

Author: Nivedita Menon

Publisher: Zubaan Books

Genre: Non-fiction

Nivedita Menon notes this in her book Seeing Like A Feminist. She is an influential feminist academic, who briefly taught in Lady Shri Ram College, University of Delhi, and is currently a professor of political science in Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. What probably heightens her ability to see through the flawless nude makeup of our patriarchal culture is the fact that she was brought up in the Nair community of Kerala which, until her grandmother’s generation, was matrilineal.

Seeing Like A Feminist is not exclusively about the challenges faced by feminism in India; because this is a book on feminism, it belongs to the library of the global and intersectional movements of feminism that has no borders. It covers a wide range of issues like the Hindu Code Bills, the Pink Chaddi campaign that was heavily criticized by the media, ‘gender verification’ tests for the Olympic Games, Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, gender performativity, the Women’s Reservation Bill which was never implemented, and the feudal callousness of the Indian middle classes towards their “servants”.

What makes the experience of reading this book richer is the author’s emphasis on laws, one of which was The Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, which humorously enough, did not define what was indecent. Although implemented for women’s emancipation, such laws eventually failed because of the loopholes that were introduced because of homogenization- an approach that was obviously doomed because of our religious diversity.

One of the many things that piqued my interest, is the subject of marriage. Menon’s views on marriage as an institution of patrilineal virilocality, and on the prototypical family as an institution based on patriarchy are unequivocal.

If you bring fundamental rights into a family, and if every individual in the family is treated as free and equal citizens, that family will collapse. Because the family, as it exists, is based on clearly established hierarchies of gender and age, with gender trumping age: that is, an adult male is generally more powerful than an older female.

This book sheds light on the staggering truth that men lactate too, and how that should open up possibilities in the realm of child-rearing, instead of being something that should make men feel emasculated (a misogynist word publicly despised by feminist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in her TED talk). There are other revelations in this book that are shocking rather than surprising. Widow is a term of abuse in Hindi. The patriarchy forces women to prefer prostitution over domestic work, because of the unrewarding, humiliating and exhausting nature of the latter.

With rawness and fecundity, Menon expands on issues like the callous treatment of domestic workers by the middle class and makes the reader see it as not only a human-rights issue but also a feminist one. The work of household chores and child-care are expected to be performed solely by the woman, or by a domestic maid (usually a woman) under her supervision, while the bearers of sperm never miss a meeting. It is not far-fetched to imply that if women stopped performing this unpaid labour, our economy would crash.

It is the unpaid labor of women on which the economy is based.

So expansively thorough is its reach on current issues that this book may well be a condensed Indian version of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. Gloria Steinem, whom Menon quotes twice in this book, once said in an interview, that intersectionality is like a patchwork quilt. We belong to patches of different colours and patterns, all separate, and yet sewn together. This book is like that patchwork quilt, paying equal attention to issues faced by bourgeois feminism, the gay movement, the dalit movement, domestic workers, and so on.

Singing through the pages of this book is the ideology of the French Nobel Prize winner, Romain Rowland.

Where order is injustice, disorder is the beginning of justice.

The book concludes with hope that patriarchy is not as invincible as we think. Menon describes the patriarchy as an assembling of structures in which we all participate either consciously or unconsciously. However, it is when we refuse to participate in it that the structures do not get to close their gates with a satisfactory click. Seeing Like A Feminist is what disorganizes the settled field, and opens up multiple possibilities rather than close them off.

Menon writes humbly that this book should not be seen as the feminist position on anything. Yet, it is a crucial look at the world through the lens of a feminist and a revolutionary. This book is a must read for a reader who wishes to gain an expansive knowledge of the history of feminism in India – a history that has been conveniently erased from our books, and the cultural narrative. It is a reminder, especially to those who have given up on feminism that the efforts of women’s liberation movements in South Asia have been anything but dormant throughout the past century. It is seemingly slow progress, but necessary and worth it.

Also read: Book Review: Americanah By Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, The Politics Of Writing About Love

Featured Image Credit: Alchetron.com

Read more about Seeing Like A Feminist here

About the author(s)

Nalini sharma is a fresher in the ever-expanding school of feminism. In her spare time, she can be found writing cheesy poetry and watching funny YouTube videos.