If you are asked to make a list of Indian women in STEM and your list begins and ends with the name Kalpana Chawla, you’re not alone. In the process of compiling this list, as a science student myself, I was embarrassed at how few Indian women I knew in the field and how little I knew about their lives. There are in fact, numerous Indian women in STEM who have contributed towards shaping science and in that process our lives too. Hence, it is important we know them, appreciate them and acknowledge their struggles.

We need to see these women in mainstream media. We need to hear their stories in our textbooks, so that young girls know that a career in scientific research is as good an option as any other.

The following is a list of Indian women researchers from the past who left their mark in their respective areas of expertise. They are examples of how it isn’t impossible to navigate this male dominated field and a reminder that many more women will follow.

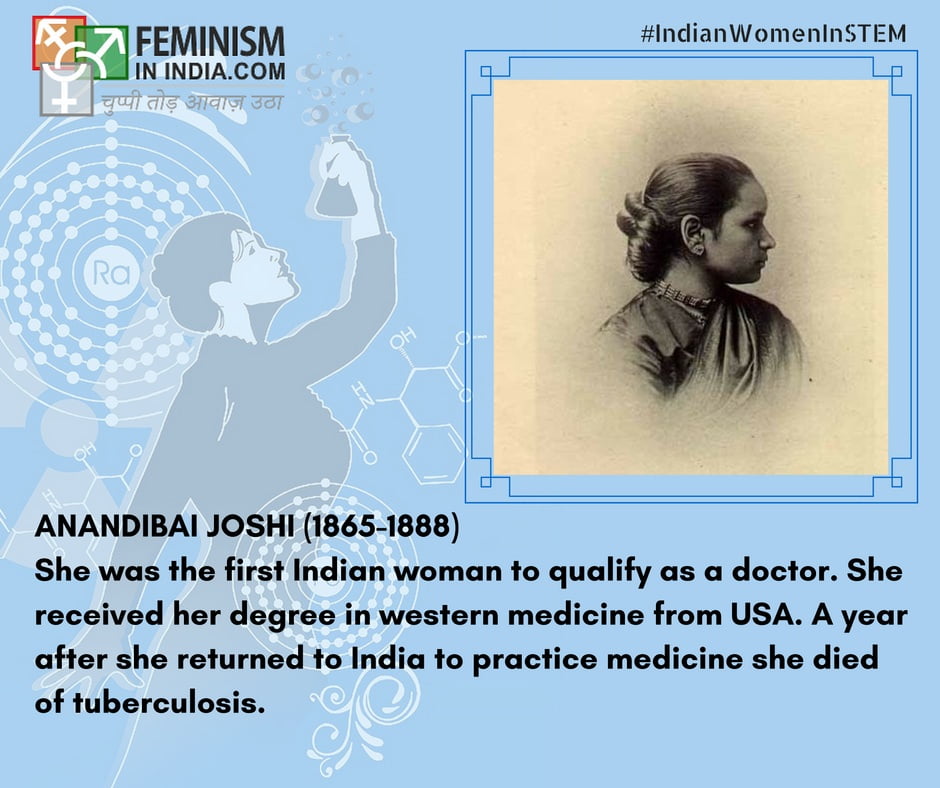

1. Anandibai Joshi (1865-1888)

She was the first Indian woman to receive a medical degree. Her life is remarkable in every way; she belonged to an orthodox Maharashtrian family and was married off at the age of 9 to man 20 years elder to her. She lost a baby boy at the age of 14, 10 days after she delivered him. Many regard the incident as her motivation to pursue medicine. Her husband was supportive of her dreams and hoped she would be a pioneer in women’s education in the country. She traveled all the way to America to study at the Women’s Medical College, Pennsylvania (WMCP) from 1883-1886. In her application to the WMCP she wrote:

“[The] determination which has brought me to your country against the combined opposition of my friends and caste ought to go a long way towards helping me to carry out the purpose for which I came, i.e. is to render to my poor suffering country women the true medical aid they so sadly stand in need of and which they would rather die than accept at the hands of a male physician. The voice of humanity is with me and I must not fail. My soul is moved to help the many who cannot help themselves.”

On her return, she contracted tuberculosis and died within a year.

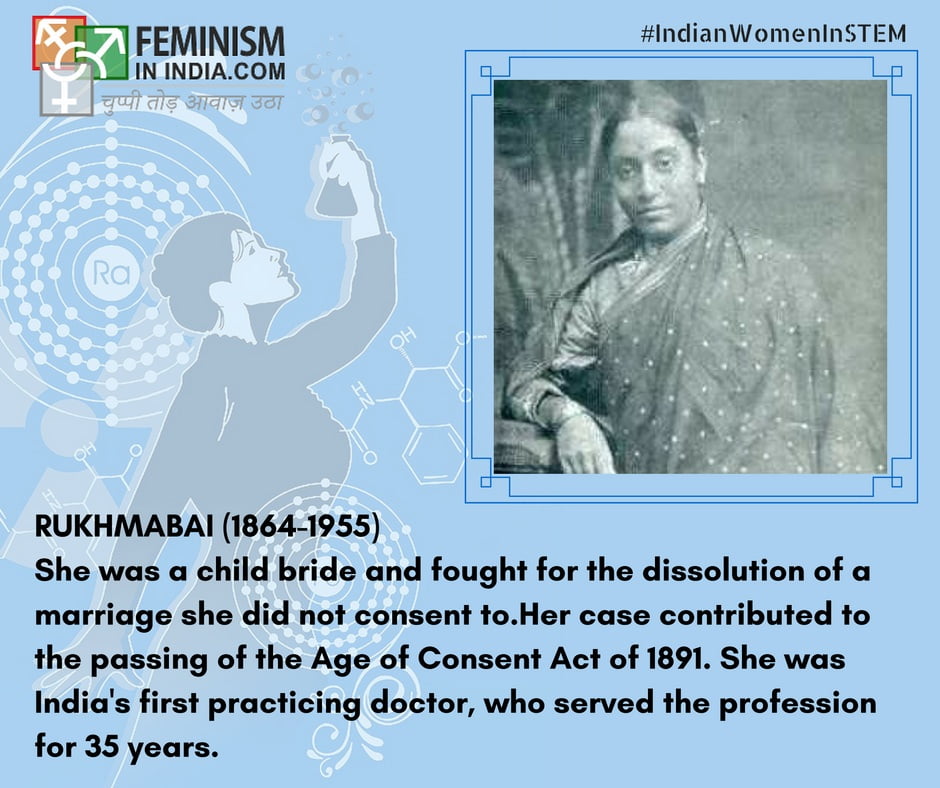

2. Rukhmabai (1864-1955)

She was the first practicing female doctor of India. Her medical career spanned 35 years, a career she built with a lot of struggle withstanding constant opposition. At the age of 11, Rukhmabai was married off to 19 year old Dadaji Bhikaji. She stayed with her parents even after marriage to continue her education with the support of her stepfather Sakharam Arjna who was an advocate for education and social reform. When the time came to go back to her husband, she refused to do so and argued that the consent to marry him was invalid because she was too young at the time. In what is now a landmark case that led to the passing of the Age of Consent Act of 1891, her husband filed a case against her when she was 22 claiming his conjugal rights. The court did not rule in her favour, and to avoid imprisonment she had to pay monetary compensation for the dissolution of the marriage. Her struggle was instrumental in the progress that was made in the coming years on the age of consent and a woman’s freedom of choice in marriage. In 1889 she went to the London College of Medicine to pursue a degree in the field. After her return to India, she served as a doctor for several decades.

3. Janaki Ammal (1897-1984)

She was a world- renowned Botanist who hailed from Kerala. She received her PhD in botany from the University of Michigan. She spent several years in England pursuing research. Dr Subramanian in his essay chronicling her life speculates that the matrilineal system in Kerala at the time, where women were encouraged to pursue education, may be the reason for the support she received from her family. She studied the chromosome number and patterns of several plants and published a compilation of her findings in ‘The Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants’ which she co-authored with C D Darlington. Her work gave insights into the evolution of these plant species to future scientists. In 1951, Jawahar Lal Nehru personally requested her to return to India to head the country’s Botanical Survey. She also worked at the Sugarcane Breeding Institute in Coimbatore, and was part of the team that successfully produced a hybrid variety which was sweeter and more suitable for Indian soil than what was grown at the time. She received the Padma Shri in 1977. The Janaki Ammal National Award for Taxonomy instituted in 1999 is named after her.

4. Kamala Sohonie (1912-1998)

She was a Biochemist by profession. In 1933, after graduating from Bombay University she applied to work in Dr C V Raman’s Lab at Indian Institute of Science, but was turned down because of being a woman, despite being high up on the merit list. After some relentless persuasion, he agreed to keep her for a year on probation. Later on, impressed with her work, he let her stay on. In her later years, she recollected that “Though Raman was a great scientist, he was very narrow-minded. I can never forget the way he treated me just because I was a woman. Even then, Raman didn’t admit me as a regular student. This was a great insult to me. The bias against women was so bad at that time. What can one expect if even a Nobel Laureate behaves in such a way?” Thankfully, her struggle did pay off because consequently, Dr. Raman began admitting women researchers in his lab.

At Cambridge, in an original discovery, she was able to demonstrate the presence and activity of cytochrome oxidase, an enzyme involved in cellular respiration. In India, she worked on different varieties of pulse and on the nutritive value of the drink Neera, both of which were relevant to combating malnourishment in India. She was the President of Consumer Guidance Society of India from 1982-1983. She was also a recipient of the Rashtrapati Award.

5. Anna Mani (1918-2001)

She was a renowned Indian scientist with several published papers in Physics and Meteorological Instrumentation. As a graduate student (1940), she worked in Professor C V Raman’s Lab at the Indian Institute of Science. She later became the Deputy Director General of the Indian Meteorological Department, Pune (IMD) from where she retired in 1976. Most of her work revolved around designing and improving weather instruments. Being passionate about environmental issues, her major areas of study included solar radiation, atmospheric ozone and wind energy. She was instrumental in developing India’s Ozonesonde – an apparatus that is used to measure atmospheric ozone, adding India to the limited list of countries in the world that could do so at the time. The Wind Energy Data for India that she published in 1983, went a long way in India’s successful attempts to set up wind energy farms across the country. It is a failure on the part of our academic system that she was denied her PhD from the University of Madras, on grounds that she didn’t have a Master’s degree, despite having finished her doctoral thesis.

6. Asima Chatterjee (1917-2006)

She was a chemist from West Bengal. Her field of specialisation was phytochemistry (The study of chemicals derived from plants). Known for her extensive work on Vinca Alkaloids which is now used in cancer therapy, she is also credited with the extraction of certain anti-epileptic and anti-malarial drugs from plants. She has published over 400 research papers in esteemed scientific journals and is extensively cited even today. She also established the Chemistry Department at the Lady Brabourne College in 1941, which is one India’s premier institute for women’s education. Being the first female recipient of the prestigious Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar award in 1961 and the first female general president of the Indian Science Congress Association in 1975, she truly is a path breaker for Indian women in science.

7. Archana Sharma (1932-2008)

She was one of the most famous botanists India has produced. She specialised in chromosomes and genetic techniques. She developed a new method to stain and pre treat chromosomes to study them effectively, a technique which is now used worldwide for research. In what is considered to be one of her best works, she published a paper on ‘a new concept of speciation and fixity of chromosome numbers in obligate vegetatively reproducing plants’ in Nature, one of the biggest international journals for ground breaking discoveries in science. She went on to make several more contributions to the field of Cytogenetics (the study of cell structure in relation to genetic inheritance) later on. Along with her husband, she founded ‘The Nucleus: an international journal of cytology and allied topics’, in 1958. She wrote a book titled ‘Chromosome Techniques: Theory and Practice’ which is still considered a gem in the field of plant and human genetics. She received the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar award in 1975, the second woman to do so, and the J C Bose award in 1974. She was the president of the Indian Science Congress Association from 1986-1987, after which she was made the president of the Indian Botanical Society in 1989. She received the Padma Bhushan in 1984.

8. Rajeshwari Chatterjee (1922-2010)

She was the first female engineer from the State of Karnataka. It was probably the influence of her maternal grandmother, Kamalamma Dasappa, who was a pioneer in women’s education in Karnataka that made her pursue higher education at a time when it was very rare for women to do so. In 1947 with a scholarship from the Government of India, she embarked on a long and arduous 30 day journey to get to the United States of America, to pursue her PhD from the University of Michigan. She was the first female faculty member at the prestigious Indian institute of Science (IISc). In 1953, Ms Chatterjee and her husband started a research lab on Microwave Engineering, the first of its kind in India at IISc. She held the position of Chairperson of the Department of Electro-Communication Engineering at IISc, Bangalore for several years. She has over 100 published papers and 7 books to her credit. Despite receiving several awards and recognition for her work in the field, she was not honoured by her state or by the Indian Government.

Do you think we missed an important Indian woman in STEM? Let us know in the comments section.

Also read: Where Are The Indian Women In Science?

About the author(s)

Sheryl is a science graduate who now wants to become a lawyer. Her interests include feminism in pop culture, cats and Netflix.