On January 25 2016, Women and Child Development Minister Maneka Gandhi, who is part of a ministerial panel including Home Minister Rajnath Singh to discuss the proposed Disability Bill, raised objections to the bill claiming that it does not lay criterion for determination of mentally disabled persons.

“It (bill) does not differentiate between mentally ill and mentally disabled person. But there is a difference between the two. If a person is mentally ill like schizophrenic, how can he be given a job,”

The statement quite obviously did not go down well with disability rights activists, especially people having and/or working on mental illness. In response to Mrs. Gandhi’s claim, Equals Centre for Promotion of Social Justice, a disability rights advocacy organization based in Chennai, is leading a photo campaign called #WeCanWork –putting together pictures of people with mental illness holding placards telling Mrs. Gandhi they can work.

Earlier last month too, in his latest Mann Ki Baat broadcast on 27th December 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi appealed to the public to adopt the word divyang (divyang body) while referring to people with disabilities instead of viklang (disabled). As expected, the suggestion did not go well with the disability community and/or people working on disability.

The National Platform for the Rights of the Disabled has issued a letter to Mrs. Gandhi expressing their disappointment and urging her to have meetings with organisations/persons working with those having psychosocial disabilities to get a clearer picture. The full text of letter addressed to Maneka Gandhi on January 28 can be found here.

It would be pertinent to point out that persons with mental illnesses, including those with schizophrenia, have the right to work under current Indian law. In a 2010 judgment, the Bombay High Court upheld the right to be employed, of a man who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and who was forced to resign from his job at the Shipping Corporation of India, because the employer refused to transfer him to a shore-based position (Edward D’Cunah v Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities). The High Court held in this case, that under Section 47 of the Persons with Disabilities Act, 1995, the Shipping Corporation had a statutory duty to accommodate an employee diagnosed with schizophrenia, by transfering him to another suitable position. The High Court ended with the following words by Tagore: “The problem is not how to wipe out the differences but how to unite with the difference intact”. This judgment was affirmed by the Supreme Court of India in October 2013.

Spokesperson from Equals, Amba Salelkar, lawyer and disability rights activist explains how persons with mental illness or psychosocial disabilities have always been considered to be persons with disabilities even under the 1995 disability law. After India ratified the CRPD this was not even a matter of debate. In fact livelihood was one of the focus areas for persons with psycho-social disabilities since it talked about recognising the right to live in the community and not in institutions. As it is persons with psycho-social disabilities are underrepresented in the disability movement and this discrimination brings them one step further down.

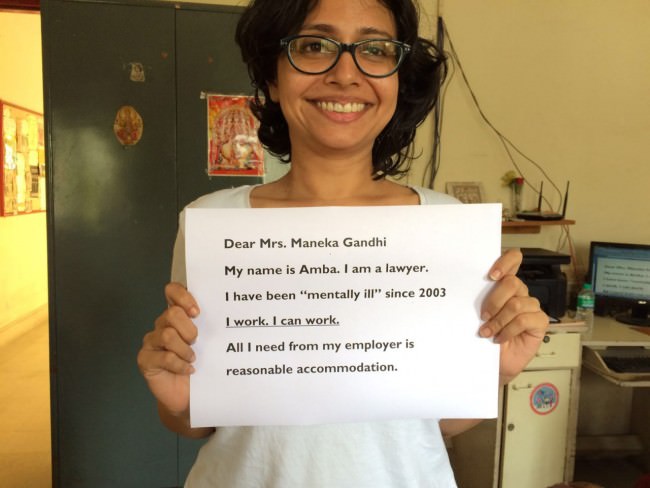

Inspired by online photo campaigns like #BlackLivesMatter, #INeedFeminism and the likes, they took photos of each other, but were unsure how much support they could garner without being accused of delaying the bill further. “I spoke about my ability to work, Meenakshi spoke as an employer of sorts, Rajiv as a colleague and in solidarity. Meenakshi says that she teared up slightly while taking my photo – she couldn’t believe that in this day and age I had to hold a placard that said I can work. She’s right, it is kind of ridiculous but apparently it had to be done“, says Amba.

Dear Mrs. Maneka Gandhi,

My name is Amba. I am a lawyer. I have been “mentally ill” since 2003. I work. I can work. All I need from my employer is reasonable accommodation.

They then reached out to their colleagues, people they work with in the field, persons with psychosocial disabilities and community workers from the Bapu Trust, Pune, PSDs from Better Chances, homeless PSD from Iswar Sankalpa Kolkata and their employers, among many others. The response has been brilliant; they have 56 photos so far including psychiatrists, writers, activists and even a person who negotiated the CRPD. They aim at the very least that the GoM does not make this observation part of their report and that it will help people think differently in terms of their potential to be allies and employers and coworker.

Queer, feminist activist Pramada Menon also writes in agreement. “Marginalization comes easy to us. Disability in all its forms is complex and requires us to understand the nature of it rather than make irresponsible statements or claim divinity for the disabled. There are numerous people who have a range of mental illnesses and denying them the right to work is discrimination. What we need to ensure are support services that can be accessed, so that the individual in question can get whatever help that is required to enable them to live out their life to the fullest.” She further applauds the campaign. “The campaign is amazing because it has brought mental health out of the closet and made it visible. So many of us are grappling with so many different challenges and yet we function, we live, we love, we work.”

Val Resh, who describes herself as a person with many labels, roles, and existences, says, “I am not disabled because of my schizophrenia. I am disabled because society is disabled by their strange assumptions on how their world functions.” In this Facebook post, she explains the issues of politics and legality in India and individuals who think ‘schizophrenics’ are useless. She concludes by saying, “I am a PERSON first and always who lives with Schizophrenia. I am NOT an adjective, a coolness quotient, a psychotic fashion for media, or a lesser being.”

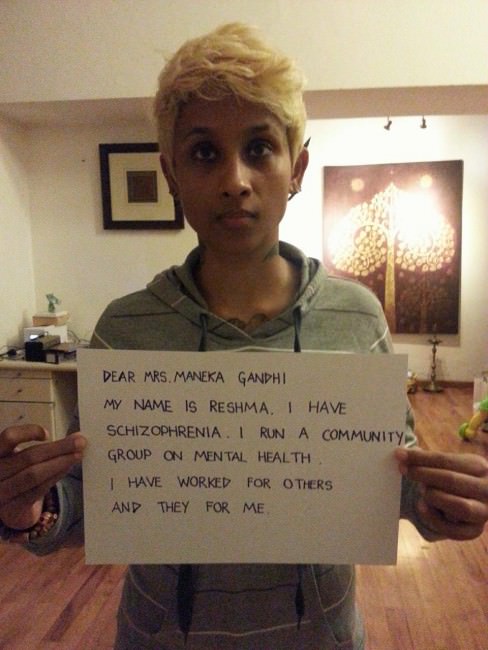

Dear Mrs. Maneka Gandhi,

My name is Reshma, I have schizophrenia. I run a community group on mental health. I have worked for others and they for me.

Ratnaboli Ray, founder and managing trustee at Anjali – a mental health rights organisation, is outraged by Mrs. Gandhi’s statement and writes in her Facebook post. “This kind of low expectation from persons with a history of mental illness is a construct which is a huge barrier that we have to fight on the ground towards creating an inclusive society or arguing for capacity. There are an array of interventions available that provide an evidence base that persons with Schizophrenia play or can play an active role in the employment market.” She thinks the #WeCanWork campaign is great, however, stresses on multi-pronged approach to fight such deep attitudinal barriers. She suggest sit-ins, protests, op-edits and press conferences, among others.

Gender and disability rights activist and founder of advocacy group Sruti Disability Rights Centre, Shampa Sengupta has no problems in telling people about her mental health status and is part of another campaign called #IAmNotAshamed. “I have mental illness. I need therapy. I had been working on several assignments – and have good reputation at work. In fact work acts as a therapy to me. There are some good days and some very bad days. But this happens to everyone I believe irrespective of mental health conditions. I am not ashamed and I openly say to my employers about my illness.”

On the one hand, the government launched the Accessible India campaign on December 3 2015 – a nation-wide flagship campaign for achieving universal accessibility, while on the other Mrs. Gandhi chooses to discriminate between the mentally ill and mentally disabled based on her limited understanding and ignorance. Is the Accessible India campaign then only about hashtags and social media? What is accessible here and who is included?

All images courtesy #WeCanWork Tumblr.

About the author(s)

Japleen smashes the patriarchy for a living! She is the founder-CEO of Feminism in India, an award-winning digital, bilingual, intersectional feminist media platform. She is also an Acumen Fellow, a TEDx speaker and a UN World Summit Young Innovator. Japleen likes to garden, travel, swim and cycle.