In this series, Women In Power, we feature women who have done ground-breaking work in the field of gender, sexuality, women’s rights and the likes to get an insight into their lives and their work. More and more people are joining the feminist movement and working on gender and we wish to bring them in the limelight, one life at a time.

The ongoing conversations on gender and caste in the feminist discourse emphasise on the importance of Dalit women’s voices. The lives and stories of women from marginalized sections of the society are important starting points for understanding this intersection of gender and caste.

One such strong and resilient voice is the voice of Manisha Mashaal. Manisha Mashaal is a grassroots anti-caste activist, an orator and a singer. She comes from a small village in Haryana where she grew up as a Dalit woman and overcame many hurdles to become what she is today – a strong Dalit voice. Manisha is a first generation learner in her family and has two degrees to her name – a Bachelors and Master of Arts in Women’s Studies. She is a spirited Dalit activist and the founder of ‘Swabhimaan Society’ in Haryana.

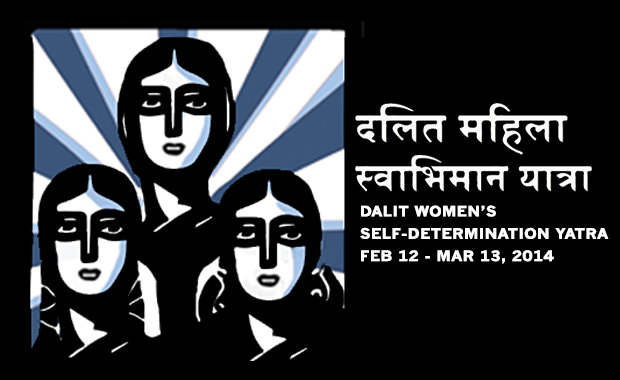

She began her activism in the year 2005, and in the years to follow, became a strong Dalit voice representing the larger Dalit community through campaigns like Dalit Women Fight and Dalit Mahila Swabhimaan Yatra. Earlier this year, she raised her voice against the institutional murder of Rohith Vemula, and has been the face of her community in the recently concluded Dalit Asmita Yatra in Gujarat.

As marginalized women stand up today for their right to a life of equality, dignity, respect, and recognition, they also demand their right to dissent and right to say no. The answers to the systemic discrimination of Dalits lies in the questions that arise from the experiences of those who have suffered the atrocities.

Manisha, along with many other Dalit women have been for long questioning the dominant hegemonic ideas of nationalism, gender justice, equality, and freedom with every word they speak.

Manisha spoke to Feminism in India about the Dalit movement and especially Dalit women’s struggle and leadership. Talking with her was not only a remarkable experience, but also a stimulating learning process.

Manisha Mashaal

Q1. What has been your experience of growing up as a Dalit girl? Tell us about your childhood and the issues you have faced because of your ascribed marginalized identity. What are your memories of facing discrimination as a Dalit woman?

When I was in third standard, I remember, I was not aware about my caste. I was studying in a government school in our village and in one of our classes my professor was discussing about animals like pigs and dogs. He asked all the Dalit students to stand up. “All the chude and chamars, stand up,” he said. I used to sit on the front bench then, and I did not stand up. So my professor looked at me and said, “Why are you not standing up, you too are a Dalit.” Everyone in the classroom stared at me with suspicion, as if I had committed some crime. I did not know why they were looking at me like that, but I do remember feeling very sad about the whole incident. I started wondering, “Is it because of my caste that professors do not ask me to get water for them? Is this why they ask the non-Dalit girls to get them water? Probably this is why our homes are kuccha homes and the zamindaars have big homes with land.” With time I realised why our small community settlement is outside the village, excluded from the rest. I grew up with a lot of unnecessary beating from my professors. I have faced discrimination since childhood.

Q2. You are an activist, an orator, a singer, an artist fighting for social rights. How has your personal journey contributed to the activist in you?

I lead my community and give speeches at a lot of places today. I also strive to work at organisational level for my community. I must tell you that even within the Dalits I belong to the maha-Dalit caste i.e. the Valmiki community. Girls from Valmiki community are not allowed to venture out of their homes. I became an activist because of my own experience of exclusion and discrimination which I faced in school, college, and later in the university. My father’s economic condition was very poor. With some help from people close to us, I somehow managed to finish my studies. We saw a lot of struggle through those years. Despite this, I feel sad that a Dalit woman finds difficulty in claiming space for herself today. A Dalit woman, especially a young Dalit woman activist has no space to make demands for herself. When I talk of Dalit women and Dalit victims, I talk of them as our real leaders, who are fighting despite the discrimination they have suffered.

I became an activist in 2005, it’s been 11 years now. From what I can comprehend of the state at an organisational level, I have failed to see any marginalized female victim getting the kind of freedom she deserves – economically and socially. Sure a lot of women have become leaders, but their economic condition and social security is so frail! They do not have a voice of their own. Though a lot has changed, the amount of discrimination meted out to us has only gone increased.

Q3. Tell us about your journey with Dalit Women Fight and the Swabhimaan Yatra. How did it start? What are your pertinent demands and why?

In November 2012, Dalit atrocities were at its peak. Many women were killed and murdered in Haryana. After undertaking some fact finding of the cases, we saw that the documents were all wrong. Many FIRs were not registered, and those registered were registered with wrong dates. Many cases were rendered false too. We felt a strong urge to do something about this and stop this discrimination. We started the Swabhimaan Yatra in Haryana for the first time during that time. We met families of the victims and survivors and negotiated with the state. We demanded rehabilitation for the survivors of atrocities of all forms, be it rape, harassment, or any other kind; and demanded lifetime punishment for the murderers. We also demanded the erasure of counter cases to the FIRs that were registered. We asked the state to compensate families of victims and look after their education. Despite our demands, the state did not pay any heed. This is what our demand always has been – Dalit women deserve to live a life of dignity and freedom.

After Haryana, we also went to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar with our Swabhimaan Yatra. Soon we realised it is not about a village, a town, or a particular city. This struggle is about all Dalits – everywhere in the country. However, the process of giving justice has been very slow on the part of the state. Since 2012, only one case has been given justice. The accused in a case of minor child of 11 has been punished for 10 years. But that’s it. No justice beyond that one case. The Karnal case happened in 2012, and the CBI investigation happened only recently. I have been attacked several times for raising my voice for these issues. When I go to file cases, people are sent behind me in cars. They want to silence our voice and make us fear them, but that is not going to happen.

In 2013, Dalit Women Fight took shape as the social media campaign of the All India Dalit Mahila Adhikar Manch (AIDMAM)‘s work around caste-based sexual violence. This campaign was launched with the Dalit Mahila Swabhiman Yatra where Dalit Women from around the country joined in our first yatra. Eventually Dalit women from around the country and the world joined and used this platform to break the silence on caste violence in our communities. Thenmozi Soundrajan was an artist in residence with the campaign who did social media training with our group. When the group was started, we were not avid users of Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter. It was in 2013 that we first used the hashtag #DalitWomenFight. We took the Yatra to USA as well. We spoke in about 22 universities about our struggles. We talked about how Dalit women are suffering and being discriminated against.

Dalit Mahila Swabhimaan Yatra

Q4. From Dalit Women Fight to Chalo Una protest, what have been the significant transformations in the Dalit movement according to you?

Yes definitely there has been some transformation. Earlier the media used to remain totally mute on our issues. In all these years, we took workshops trying to educate people on how social media and mainstream media is not benefiting us. It was not helping our cause, our struggle. So we endorsed the idea of creating and furthering our own voice through the same media, but by creating our own counter media platforms. We always knew that unless we do not get that space, our problems will not be known to the wider public. So the Dalit movement that was taking shape then has benefited a lot from social media, because Dalit students have started using these platforms for themselves and their community. That way, we can find out what is happening in Uttar Pradesh, in Haryana, in Bihar and other states. The Dalit movement is shaped by this transformation. The women’s struggle in Dalit movement is only beginning to find its space, and we are working on that. Dalit Women Fight is one such step towards the liberation of Dalit women.

Q5. You are a resilient supporter and a strong leader of the Dalit Asmita Yatra. Tell us about your experience of leading the Una march, as a Dalit woman amidst other men who were leading the movement.

My observation says that Dalit women have been neglected from the decision-making bodies of organisations. When I was a part of the Dalit Asmita Yatra, I realised that though Jignesh Mewani was leading the rally, the left movement was organising and dominating the entire Yatra. Whenever we gain some momentum, the dominant groups come and start behaving as if they, by default are the leaders of our movement. So the Dalit movement starts weakening a little. I do not want this movement to start moving backwards at any cost. That is why I stress for Dalit women’s leadership. We know how to get leadership in our hands, our entire life has been a struggle for this sole reason. There is no way we are running away now. Our struggle will continue.

I was a part of the Una Yatra along with Rajni, we both were there. I was witness to the solidarity women showed us when we passed through villages and shouted slogans. Many women from different villages joined us and continued walking with us. They walked hand in hand from one village to another. The double discrimination that our women face has made them so strong that they are absolutely capable of fighting and leading our entire Dalit struggle. It is because of this struggle that they can face and defeat the double faced state.

I remember when I went on stage to give my speech, some people questioned, “If you are from Haryana why are you giving a speech here?” Someone even snatched the mike from my hand and said “This is Gujarat’s struggle, not yours.” I retorted, “Look, this is our struggle, this is Dalit struggle. It’s not about Gujarat, Orrisa, or Bihar. Just because I am from Haryana does not mean the struggle in Gujarat is not mine or that my struggle is located elsewhere. Our struggle is Dalit struggle.” The atrocities that we face are present in all states. The states can differ, our experiences of discrimination exist in all of them. That is why our fight is for Dalits everywhere and we are an integral part of it. We are not going to run away from our fight. I am not going to die like this, I am going to live a leader’s life and die a leader too.

At Una, I asked some women, “Are you upset that we have come here despite the fact that we are not from Gujarat? Should we leave?” They responded, “No, that is not what we meant.” But when we had to spend the night, we had no place to sleep. No one asked if we needed help. Others went away as they already had a place to sleep. You see, these dominant people come and act has if they own our struggle. They want us to believe that they are fighting for our emancipation, and then they shower sympathy on us. Are they doing us a favour by fighting for us like this?!

Every day at Una brought new challenges. But the pain and suffering of Dalits everywhere is so intense, the challenges seemed nothing in front of the pain. So we kept fighting. We continued the rally with the hope of getting azaadi from the discrimination we have faced for so long. But on 15th August, when I was sitting on the stage, I remember some people wanted me off the stage. They tried doing it 5 times! But I did not leave my stage, because I know I need to occupy my rightful space. No one is going to give that space to me, I have to create it for myself. When I was about to give my speech, some men came with a stick in their hands and said, “You have been told not to talk.” Someone even came and sat in front of me on the stage, despite the fact that there was actually no space to sit in front of me. When an Ambedkarite took the mike in hand to speak, they would say that we do not have a lot of time. A mere eye contact was enough to tell that their expressions changed after looking at us.

Also read: Hypocrisy Of The Mainstream Media: Lessons From The Dalit Asmita Yatra

Q6. What do you expect to see post Una? Do you think the movement has created space for Dalit women to emerge as leaders of the Dalit community?

Definitely! I experienced this in Swabhimaan Yatra and Una both. It is my experience that Dalit women walk with everyone, they do not leave anyone behind. In our struggle, our brothers stand on an equal footing with us. At Swabhimaan Yatra, we found young Dalit women who could lead us in every village that we visited. But in Gujarat, I was surprised this was missing. I started thinking about the importance of a separate space for Dalit women’s struggle within the larger social struggle. Because one, we are not given the space we deserve and two, other people represent us. We need to lead our movement, we want our brothers to be a part of our struggle. We want to represent our struggle. Dalit women can lead not just Dalit women but lead all Dalit people.

Even with all its shortcomings, our movement should give Dalit women the space to lead and assert. There are 50% women in this country. There were so many marginalized people at the rally, my slogans were posted and spread everywhere. There was a lot of strategical thinking going on about the fact that a woman like me was leading the rally. The significance of a women’s struggle is that equality becomes the driving force of the movement. I could see that in the huge struggle for our people only 50% voices were heard. Where were the women? Who will talk of swatantra for those 50% women? I also realised that we need a movement and protest led by Dalit women for Dalit women and the community. I think we will have to start this movement.

Q7. There has been some criticism over upper caste people assuming leadership in the Una protest. The Dalit movement’s significance lies in the fact that it is an Ambedkarite movement led by the Dalits. What message do you have for (upper caste) people who are trying to be allies with the Dalits?

We want total and complete freedom. Our demand for freedom is not of the kind where we get freedom and yet we remain under the leadership of the dominant. So when the word azaadi is uttered, my question is which azaadi are you talking about? Whose swatantra are you talking about? Whom are we taking along with us when we claim that we are fighting for freedom and emancipation? All these questions are important. On one hand people are saying, “I am an ally in the Dalit struggle because I understand their pain.” and on the other hand they are saying, “I am a Brahmin!” They will carry their caste with pride and then claim that they are not Brahmin-waadi in their ideology. This is what casteism is, no? To show you are above the marginalized and to show your position of power. Are they really not aware of the fact that they are being casteist? They enter our movement and talk on how they have vouched for annihilation of caste from this country because they believe in humanism. If that is the case how can they carry their dominant caste with so much pride?

My point is, it is true we all need to somewhere come together. It is important that we take a stand and fight for freedom. But the problem is, those supporters from outside the community who claim to have read Babasaheb do not think twice before claiming leadership in our movement. We are facing atrocities from 3000 years because they have been the leaders all along! If they really want to support us, they should do it in a way that does not put them in front of our struggle. I want to tell them to not occupy our stage. This is the one thing that has been consistently happening. What freedom do you talk of if all you want to do is continue this dominance?

Every movement is a mass movement, it is not an individual’s movement. But what people need to understand and say out loud is, “Yes, we know your suffering is enormous on every scale, and we acknowledge that we have not been at the receiving end of that suffering, so we respect your struggle and your stand.” I don’t think any Dalit will say no to this kind of support. I know many allies from outside the community who are not power-hungry, who are not here to claim our space or to become our leaders. They are our genuine supporters, because they are compassionate in their approach and aware of their privileges. Even if they have a chance, they reject positions of leadership, because they want to subvert the hegemonic power relations too. They tell us, “We will support you from behind, you must lead.” I welcome such supporters with all my heart.

Q8. Do you think the anti-caste/Dalit movement needs to focus on the question of sexism within the movement? How important is it for Dalit women, who are the most oppressed in the context of class-caste-gender structures, to have their own space to augment their voices and bring their problems/experiences on the table? How are Dalit women doing it?

Yes, this is an important point. Caste, class and gender are important issues in every movement. Look at any big organisation in metro cities, people talk of ‘rights’ like it is some fashion statement or some buzz word! All they shout is ‘Rights!’ But I want to ask them, do you really have any safety mechanism for the women from marginalized communities who are standing with you and fighting for these rights? They reject our pleas for safety because they think we belong to the ‘grassroots’, forgetting that it is because of us that their organisations are running successfully.

The comment made by Jignesh Mewani at Una was also problematic. Instead of saying he would marry his sisters in Valmiki or Muslim community, why did he not say that he would instead marry a girl from Valmiki community or Muslim community? If he is leading a jan-andolan, how can he claim authority over his sister’s life? If I am a leader, I have to set positive examples and act on them. Like I always say, the fact that I am a leader is not important, what is important is that I shape as many Dalit girls into leaders like me who will take the struggle ahead. If you are talking about setting an example, you should first talk of yourself and not of your sisters or others.

Q9. You have been using social media to talk about the Dalit movement. Platforms like the Dalit Camera have done a brilliant job of giving voice to the marginalized by using technology and social media. How do you look at social media as a space for ‘doing activism’?

When I first heard of Facebook, I did not know much about it. I only knew that people pass information to each other and talk with each other on Facebook. When Themnozi started Dalit Women Fight, she told us how we can use these platforms – be it Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter. I remember when the Swabhimaan Yatra was going on, she told us how to post things on Facebook. So I started using social media and started educating other girls too. For example, if some girl did not have a mobile phone, I would try and arrange a phone for her and then teach her to share her story and reach more people. I used to tell them why this is important and how we can maximise our voice on social media.

Without social media my legacy, my leadership would have remained restricted to my village and to select few people whom I was working with. Social media has provided us with such a strong voice that we are now international. Our voice, struggle is a story that has reached different corners of the world and so many people know about it. Dalit voices can be asserted loud and clear because of social media, and I think this is really great!

Q10. As a female anti-caste crusader, how do you navigate the intersections of gender and caste in your lived experience as a crusader and a fighter?

I have observed in almost all the programs that I attend, people pick up the mike and say things like, “I want women to become leaders and lead our fight.” But these people do not want their own sister to become a leader, they want other women to lead. When I say that we should believe in gender equality and request everyone to bring their sisters in the struggle, they are not ready for it. They give reasons like their sister cannot even talk with confidence, how can she lead the community. They tell me they are more worried about the fact that they will have to look after them all the time during the movement. So you know, this patriarchal mind-set is so severe, they find it difficult to accept that a woman is demanding the leadership of more and more women. They think only men can take strong, quick decisions and women will not be able to take responsibility properly. But I am happy to say that this has changed to some extent. A lot of men, after looking at me, have become confident that their own sisters too can lead. They have told me, “Manisha ben if you can fight for our emancipation then we will bring our sisters along too.”

Yet a lot of people critique that I am a woman and I lead the community, I can feel they do not respect me at all. As Dalit women, we face dominance from outside the community, and to some extent from inside the community too. Our fight is much more difficult than it looks. It starts with wanting to walk on the roads, to leave our homes, to assert our voice. Then we have to face the wrath of the upper-caste communities. They never look at us with respect. They think of us as someone less even if we are educated. Our gender when combined with our caste, makes us dirty in the eyes of the upper-castes.

In the end I just want to add, I strongly believe that the struggle of all marginalized people needs unity and strength, but at the same time, the movement has to ensure that women from the community get recognized as leaders. If Dalit movement has to succeed, then Dalit women have to be in a position of power and decision-making for themselves and the community at large, because they can become leaders – they should and they will.

Also read: Meet the Women Behind #DalitWomenFight Trying to Take Down ‘Caste Apartheid’

Featured Image Credit: Thenmozhi Soundararajan/Dalit Women Fight

About the author(s)

Nupur is a graduate in Women’s Studies. Interests include research, academia, gender, sexuality and politics.

Nicely done interview Nupur. The questions you had asked were really good 🙂

Great interview! you Nailed the all interview question