Image Credit: Pinterest

That a “woman’s opinion is the miniskirt of the internet”, is an adage made almost legendary by Laurie Penny. However, miniskirts, or sartorial choices of any kind, are hardly the only things that provoke patriarchal mindsets to lash out in all their toxicity. So, a woman’s opinions are hardly the only reasons that make her the receptor of trolling and abuse online. The aim and design of the online troll is to shame, discipline and silence women whose opinions are contrarian to theirs. However, it is not just a woman’s words, but also her visual self-representation online that is misused, abused and misappropriated into articulations of male desires, fantasies and forms of violence.

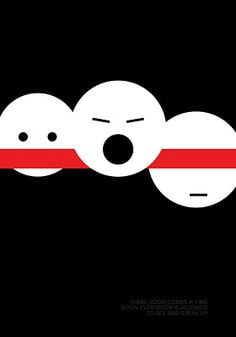

And all this, under the convenient garb of “free speech”— a lofty tenet of democracy, now reduced to a misappropriated tool used to suffocate that very same democratic spirit of the internet. While it is the need of the hour to engage in nuanced debates on what makes the internet democratic, we must beware of simplistic panegyrics of “free speech” which would excuse oppressive language and behaviours online. More so, because online violence against women has moved on from “speech” into the realm of criminal activity— often just a thin line we must not lose sight of.

The abuse of women in digital spaces, or by using digital means, has taken on various forms. It ranges from verbal abuse such as trolling, body shaming and rape threats to more insidious forms of violence such as doxing, malicious impersonation, non-consensual porn (like revenge porn), ‘creepshots’ and even rape videos. These are all dangerous extensions of what many are quick to paint as “freedom of expression”.

An important component of such abuse is that one would probably not say or do the same things if the person was face to face, as that would unquestioningly be an act of crime. However, online spaces provide abusers the smokescreen of anonymity and impunity, as well as immunity through physical distance which causes moral lines to blur, fuelling the audacity of the abuser.

When a Jessica Valenti or a Shehla Rashid are flooded with rape threats, there is no way of ensuring that these threats remain just that, and not turn into destructive action. There is always the fear of online abuse leading to offline crimes such as stalking, extortion, blackmail. Valenti says of rape threats to her 5-year old daughter, “I am sick of saying over and over how scary this is”—because the victim cannot just “calm down” thinking that the online abuse will not be followed up by real violence. Therefore, these problems progress way beyond the ambit of merely speech or expression. The key is to think in terms of consequences as well as contexts. In such cases, it may not be enough to appeal to the “Community Standards” of the social media platform and ‘blocking’ the offender, because several more ‘fake profiles’ of the same individual can mushroom within seconds.

The case of the Icelandic woman, Thorlaug Agustsdottir, proves the dangers inefficacy of social media “community standards”, in this case, Facebook. She thoroughly protested against a violent image of naked, bruised woman chained against something concrete, spotted on a Facebook group named “Men are better than women”. But that resulted in her photo being on that page, photoshopped into being bruised and bloodied, along with several comments containing rape threats and other severe bodily harm. But on reporting it to Facebook along with several other friends, the ghastly image was not found violating Facebook community standards. The social media giants swung into action and eventually apologised only after Thorlaug reached out to the local press.

Also Read: If Facebook Ignores Online Harassment, It Promotes It

As Jillian York argues, there are certainly several problems with privatising censorship, of equipping private companies like Twitter and Facebook with the power to define ‘hate speech’. But that is exactly the point— the process of reporting violence on Facebook through the existing channels, involves a slow process of reporting and a barely transparent method of redressal. Instead of privatising the process, it should now be incumbent upon such companies to democratise their “Community Standards” and implement a nuanced approach towards gender-based violence online. There are thousands of pages on Facebook displaying horrifying examples of sexism, but they evade censure under the garb of “controversial humour”.

A piece of misogynistic content might be a site of “controversial humour” for someone, but might appear normalised or even aspirational for others. Amplification of misogynistic, predatory visuals and/or words on aids in normalising subtle forms of violence which are already pervasive. As was seen in a recent commercial advertisement by the garment brand Jack n Jones featuring actor Ranveer Singh. The point is not to say that the actor Ranveer Singh or the garment brand for that matter are harassers, but that as influencers, they are setting unreal standards for those who aren’t conditioned to question it and are endorsing toxic behaviour in more ways than one.

The dictates of free speech do not preclude the rights of another group of people to express with equal freedom. When sexism and misogyny are called out, it is not an attack on free speech, but a critique of the deft misappropriation of a fundamental right by the privileged sections of the internet and society. Calling out misogyny, demanding safe online spaces and clamouring for an egalitarian linguistic framework on the internet is not indicative of feminists’ own brand of extremism, but shows a more informed, self-aware approach towards censuring and censoring language that further victimises those who have traditionally faced institutionalised oppression.

The problem occurs because spaces of expression and speech are rapidly appropriated by those holding social power. This is how the internet has gone from being imagined as a sexless cyborg at the time of its birth to being critiqued as a space that has failed to be feminist, or equal in any which way despite its fascinating potential. This misappropriation of the free speech totem is as menacing as men’s rights activism—a reactionary and stubborn claim to freedom, nay, the power of expression over others.

The question is not about what constitutes abuse or what violates community standards, it is about who occupies the position of power to enjoy freedom of speech and expression online. It is simply about the privileged majority—typically the urban, upper caste, cis-hetero male— unwilling to check their privileges, speech and expression in accordance with the sensitivity and vulnerability of the ‘other’ group. It is more about self regulation rather than censorship by State laws or private companies. The only way we can make ‘Internet Democracy’ truly democratic and egalitarian is through a self conscious erasure of majoritarian articulations. Sexism, racism, homophobia and misogyny masquerading as “free speech” has only done irreparable harm by reinforcing toxic, discriminatory majoritarianism, leaving behind several unfortunate marginalisations in its wake. If the free speech that incites minority-ism is left unchecked even on the internet, there will truly be no avenues left for the more vulnerable groups to exist and articulate freely.

About the author(s)

Swarnima is an independent researcher currently associated with Women's Feature Service. Can be contacted at @SwarnsB