On this day, four years ago, the physiotherapy student who was brutally raped and murdered by six men in a private bus in Delhi breathed her last on a hospital bed in Singapore. Shortly after her death, the overwhelming protest about women’s safety in the country led the government to institute the Justice Verma Committee to look into the ways that the country could improve the dismal way it treated its women.

The Justice Verma Committee Report was revolutionary. It forcefully recommended a list of reforms the government and the legislature could undertake to improve some of the deeply misogynist traits that run deep in the country. Among these were:

- Expanding the definition of rape to include any non-consensual penetration of a sexual nature, instead of the penis-in-vagina penetration that at that time stood.

- Expanding the definition of sexual harassment to include any non-consensual non-penetrative touching of a sexual nature.

- Including marital rape as a punishable offence.

- Discontinuing the two-finger test to “check for rape” by testing vaginal tightness.

- Including domestic workers within the purview of rights against sexual harassment in the workplace.

- Removing the sanction for prosecution of Armed Forces in the AFSPA areas in the case of sexual assault.

- Including gay men and transgender people within the purview of sexual assault laws.

- Instituting One Stop Rape Crisis Centers in every district with detailed instructions.

While a few of these have been instituted (including the change to the definition of rape and the discontinuation of the two-finger test), several of the progressive suggestions have not been implemented – three years after the recommendations were filed. They have mostly disappeared from the government’s conscience, with only sporadic news reports reporting the frustrating absence of implementation of any of the Verma recommendation.

Marital rape is still not an offence, with Minister for Women & Child Development Maneka Gandhi saying that marital rape cannot be applied in an Indian context just this March. The two-finger test, while being banned by the Supreme Court for use on rape victims, still has not been unequivocally condemned by the Health Minister, who said that it “may be needed in some cases for treatment purposes only.”

Just like the Justice Verma Report, the Nirbhaya Fund, a corpus of ₹1000 crore for the safety of women and girls was announced in the Union Budget of 2013. Consequently, budgetary allocations were made in the following two budgets. However, just like the Justice Verma Report, the Nirbhaya Fund languishes in the dusty corner of the government’s conscience, largely ignored in the four years that have passed since the events of December 16, 2012.

Here, we present a short timeline on the events associated with the Nirbhaya Fund and the One Stop Crisis Centers starting from its inception.

February 2013: Finance Minister announces the allocation of ₹1000 crore to the Nirbhaya Fund, whose details would be worked out by the Ministry of Women & Child Development and other related ministries. The declaration is met with the thumping of desks and applause. The fund is meant to support initiatives by the government and NGOs working towards the safety of women and girls.

December 2013: Three proposals by different government ministries to utilize the Nirbhaya Fund approved by the Finance Ministry are made public. These are: i) the setting up GPS trackers and CCTV cameras for all public transport vehicles, along with close monitoring of all public transport vehicles (estimated cost ₹1404.68 crores), ii) the compulsory addition of an SOS button on all cellphones manufactured in the country and a quick response system (estimated cost ₹321.4 crores), and iii) an SOS alert systems in trains in select zones (estimated cost ₹25.4 crores). None of these proposals are currently implemented in the large-scale way that they were envisioned, despite being approved by the Union Government in January 2014.

The 1404.68 crore project to install GPS trackers, approved in 2014, has still not been implemented nation-wide, with the government attempting to inject life into the flagging project by recently calling for its compulsory implementation – however, these plans still exist in the future tense, nearly 3 years after their sanction.

February 2014: P. Chidambaram, the Finance Minister, allocates another ₹1000 crores to the Nirbhaya Fund in the Union Budget. The Fund has barely implemented or spent any of the money from the previous year’s allocation. Only ₹200 crores is allocated for expenditure for the projects detailed above, despite their estimated cost being stated as above ₹1000 crores.

January 2015: A project for the creation of Investigative Unit for Crimes Against Women is proposed with an estimated cost of ₹324 crores. The Home Ministry directs all States and UTs to set these up on a 50:50 cost-sharing basis with the Centre. None of these Units have yet been installed, with news reports all claiming the tag ‘soon’.

February 2015: Finance Minister Arun Jaitley dumps another ₹1000 crores to the Nirbhaya Fund in the 2015-16 Union Budget, with still no clear results of any of previous projects’ implementation. ₹803 crore is allotted to the previous projects (GPS trackers and SOS helpline) that have still not been implemented.

A Women’s Helpline (WHL) Scheme is approved with a cost of ₹69.49 crore to assist women affected by violence. Again, these helplines exist in a piecemeal fashion in some states and UTs but do not exist in the universalized nature that the scheme mentions. Only ₹13.92 crores of the ₹69.49 crores have been sanctioned so far.

The One Stop Center in Raipur where women can find an assimilated list of services like medical treatment, legal aid and psychosocial counselling. (Source: The Week)

March 2015: The One-Stop Crisis Centre (OSC) project with an estimated cost of ₹18.58 crore is approved by the Union Government. The initial proposal for the OSC project was raised in June 2014, where Maneka Gandhi proposed that 660 centers would be created – one in every district. These centers were to facilitate access to an assimilated set of services like medical aid, police assistance, legal aid, psychosocial counselling etc. However, the government opined that so many buildings were unnecessary, and “the police were sensitive enough” to handle rape crises. One in every state and UT would be enough. Therefore the budget was slashed from ₹244.48 crore to ₹18.58 crores.

The number of OSCs was reduced from 660 to 36. Of these 36 OSCs, this report states that most of these are not yet set up or barely functional. Some OSC centers are functional though, like the Bharosa in Hyderabad (Telangana), Sakhi in Karnal (Haryana), OSC in Raipur (Chhatisgarh), Sakhi in Kohima (Nagaland), and Gauravi in Bhopal (Madhya Pradesh).

However, Maneka Gandhi, Minister of Woman & Child Development has proposed the next phase of 150 OSC Centres being built across the country by April 2017. Going by the trend of every other Nirbhaya Scheme, it is doubtful that this one will reach fruition.

January 2016: An investigative report by Hidden-Pockets showed the state of the One Stop Crisis Centers in Delhi. In short, they do not exist.

February 2016: ₹500 crores is added to the Nirbhaya Fund by Finance Minister Arun Jaitley in the 2016-17 Union Budget. He also announces that ₹500 crore from the unused Nirbhaya Fund will be used to install CCTV cameras in 983 train stations. This move draws sharp criticism from civil society organizations, who call it a blatant misuse of the Fund money, as it does not actually do anything to address women’s safety in specific. This scheme too however, still exists in the future tense.

April 2016: A Parliamentary Standing Committee sharply rebukes the Ministry of Women and Child Development – the nodal authority for the utilization of the Nirbhaya Fund – for allowing the majority of the Funds to lay idle while the crimes against women were sharply rising all over the country.

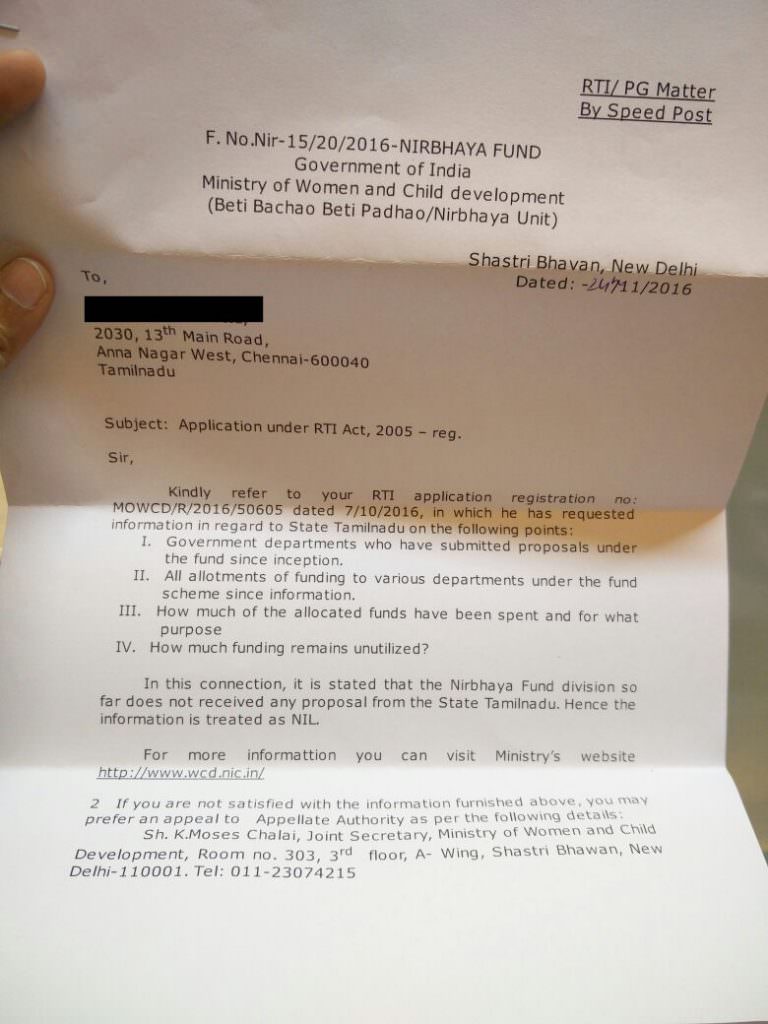

August 2016: A Central Victims Compensation Fund with ₹200 crores is set up to be used by States & UTs from the Nirbhaya Fund. Under this scheme, state governments must draw from the Fund to give compensation to survivors of sexual violence. While information about this is not freely available or exhaustive, this report shows that Karnataka has not drawn from the Fund even once to award compensation to sexual assault survivors. An RTI filed by a civil society organization in Chennai shows the same case in Tamil Nadu.

This report makes it evident that there is hardly anything to show from the government’s side with regards to measures that promote women’s dignity and safety. Four years have gone by, but there is nothing substantial to show for the crores and crores of rupees that have been pumped into this fund.

Firstly, the number of schemes proposed themselves are much too few, given the amount of time and money that have been expended on the Nirbhaya Fund. Secondly, the few schemes that have been proposed have seen little to no implementation. Clearly, women’s safety and priority continues not to be a priority for the government, despite the newspapers being bombarded daily with stories of rape, acid attacks and domestic violence. The suggestions from the Justice Verma Committee Report, if properly implemented, would do wonders for the plight of women in this country. Unfortunately, it, like the Nirbhaya schemes, is relegated to the very bottom of government’s priority list and withers in the face of State apathy.

Author’s Note: The author would like to thank Swetha D for her invaluable support and direction in the writing of this article.

About the author(s)

Asmita is a Freelance Communications Consultant, and specialises in leading digital advocacy campaigns for social and gender justice issues. When not using social media for work, she uses social media for fun (and a healthy dash of existential despair).