I recently watched the film Pink. It was not without its problems, even though it is great that some films are trying to tell stories of women differently in an industry which is as subsumed in toxic masculinity and rape culture as mainstream Bollywood. But this is not a review of Pink. This is my own experience of encountering the local court in Kolkata as a single, educated, elite woman. The role of the male saviors in the narrative of Pink– the advocate Deepak Sehgal played by Amitabh Bachchan and the judge Satyajit Dutt played by Dhritiman Chatterjee– has been rightfully critiqued by those who reviewed this film. I want to add to that by saying that these men simply cannot exist given the gender hierarchy in local level courts of Indian cities.

The middle aged babus of the local court, like other sarkari offices in Kolkata at least, assume the same role they would in a traditional familial structure. Not only should the women, who work in these offices in a superior or the same rank, accede to their sense of supremacy and general worldliness; female clients should succumb to the same hierarchy. Those of us who were taught to critique these traditional roles are seen as “over-confident” bad women.

Slowly but surely things are changing in several ways of women of different class and caste backgrounds. But different groups of women, based on class and caste, find their niche in different pockets of public life. For instance, the privileged ones – highly educated, elite, left-leaning women in Kolkata – don’t usually rub shoulders with the office-babus (bureaucrats) of these areas. We hang out in office buildings, travel in cars and Olas, and unwind in expensive places with glass doors and air-conditioning in South Kolkata. The bodies of Dalit and working class women are policed differently in public spaces; the code of honour, vulnerability to sexual violence, and the class anxiety directed towards them is also different in nature. And it is important to note that the privilege of elite women results from an invisible workforce of Dalit and working class women as domestic help and their systematic exploitation as labourers.

As privileged elite women of the city, we have the capital – both money and culture – to buy our freedom in posh establishments of the city some of which promise us safety and even dignity as potential paying customers. But we are also ghettoised in these spaces because most of the city deeply dislikes us. They dislike our sleeveless tops, they dislike our hybrid anglicized Bengali, they dislike our wealth, they despise our smoking and drinking. In a typical Bengali serial, which the working and middle classes voraciously consume, every bad girl looks like us. So sometimes we don’t even notice how we don’t go everywhere; we stick to expensive malls, cafés and restaurants. Since our families ask us when we will get married or have children, we avoid them. Even as the most privileged ones, we instinctively understand that we can assert ourselves only in selected spaces: the few meters around Academy of Fine Arts, the stretch around Presidency University, the Jadavpur University campus and a few others. We have to pay a lot to buy freedom or safe pleasure in other places like on the ninth floor of the Lindsay hotel, the small hipster cafés of Purna Das Road or restaurants in the shining Quest Mall. But what happens when we ignore these spatial regulations?

Last October I ended up inadvertently ignoring some of these rules regarding where I could be, and how I could behave. The 30th year of my life came with an ultimatum from my parents. Their honour was being corroded a little for every day that I chose to stay unmarried. My Norwegian partner and I finally gave in. We decided to get married in Norway. But this long and cumbersome bureaucratic process began with the requirement of a ‘Single status’ certificate.

Becoming a Hindu, a Daughter and a Professor By Mistake

To get this single status certificate, I was advised to go to the Bankshall Court, the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate’s Court in Central Kolkata. One morning right after the Durga Puja, I made my first ever visit. As I walked towards the iron gates of the Bankshall courthouse, I saw several men standing and soliciting passersby outside. “Affidavit, stamp paper… what do you want? Affidavit, stamp paper… cheapest deal in the market… Affidavit, stamp paper…!”

The site of many fruitless hours – The Bankshall Local Court. [Photo Credit: Moumita]

“I so-and-so, daughter of so-and-so…”

“Do you need to add my father’s name? I am an adult…”

“What nonsense? Just write what I say…“Hindu by faith…”

“Actually, I don’t want to write my religion!”

“Listen, this is the pro forma (format), you can’t change it. I just heard your name, you are Hindu right? So what’s your problem? What is your profession?”

“Actually, I teach at the university and do research. It’s a temporary 1-year position after the PhD…”

“Ok, write ‘professor by profession’…”

“No, no, I am not a professor. I guess, technically, my current position is equivalent to a temporary assistant professor rank…”

“Ok, then write junior professor. And then write that ‘I am an unmarried woman of PAN card number so-and-so.”

This went on for a while. He was clearly reciting a set format like Bengali Brahmin priests recite their mantras. He looked at me with such confusion and irritation every time I interjected that I had to stop. Suddenly I was Hindu and a professor, both of which were untrue. I did not dare to argue further about my faith and rank or their lack thereof.

At one end of the courtyard, in a shed, three men sat at old PCs typing and printing affidavits on stamp papers. I stood in a queue and heard people explain different disputes– mostly property related– to the elderly gentleman at the computer who corrected both the English and the legal terminology. The other two computers were taken. One of them was playing Salman Khan’s Tiger. Some of us were waiting in a line to solve problems of money, property, birth, deaths and marriages; meanwhile Katrina Kaif was belly-dancing in an exotic market in the Arab world of Bollywood’s imagination where white girls gyrated in hijabs and bikini tops.

I got my affidavit and went home with a feeling of accomplishment. But when I told my father that I had paid almost ₹2000 for this affidavit, he was furious. “Why did you go alone? Why don’t you listen to me ever? This does not cost more than 200 you fool! Tomorrow I will come with you”.

“Listen to your Father”: Sarkari Office Patriarchy

Time and its value depend on who one is and where one is. But time inside government offices is a strange, old, sleepy creature. And people get pushed around from one desk to the next, one department to the next, one building to the next, day after day.

After a couple of days of running around in the Writers Building, I had to return to the Bankshall court with a letter from the police asking the notary to verify that it was his seal and signature on the affidavit. I found my dalal near the gate and went back to the old man. He plainly refused to provide me a letter verifying his seal and signature. The dalal explained that even though he took the money from me, the signature was another notary’s because the old man no longer has a valid license.

I followed him to the center of the courtyard where an important looking man sat at a desk with two assistants on his side and a crowd of people around him. He had his name and a degree written in a silver and red hologram. When I approached him, he did not even look at me. He looked at the dalal and asked, “What’s the problem?” When I tried to talk to him, he looked at me angrily and said, “Did you come to me when you had this affidavit made? You paid a dalal, now why should I help you?” He said sifting through the affidavit.

“But it’s your signature, name and seal on the papers, how can you refuse to verify that for the police?” I asked him.

“You want to go the police and complain about us. Go ahead.” I could tell that this was taking a turn which was not going to help me. He seemed cross with me because I had paid way too much money to a dalal and a fraudulent notary. I had an expensive flight ticket and the fragile honour of my extended family to worry about at this point. Since it was quite clear to me that this entire system is dubious, I offered him money too. Surprisingly, he no longer wanted money. Even more surprisingly, the fact that irked him most was that the affidavit said I was junior professor at some university abroad.

“How can you say you did not understand you were being cheated? I see here you are a professor!”

I tried to tell him that it was not possible for me to understand this system because there are no written rules anywhere. I tried to point out that I should not be punished further for being cheated by men who are sitting and working next to him.

“Women like you… you get degrees, you will now teach the youth… you are a professor! You know nothing! Zero! Zero! Uneducated women in villages are far better models for the youth!”

At this point, the lawyer was screaming at me, red in the face, while more and more men were gathering around us. I tried to argue with him saying that my career has nothing to do with this problem. In the meantime, his assistant was pulling me close and explaining, “Sahib has a bad temper. But you have to be reasonable. What do you want? Do you want to fight or get your work done?” While this man was shouting at the top of his lungs saying things like “Women like you have no manners, only degrees! How dare you rub your degree in my face?”

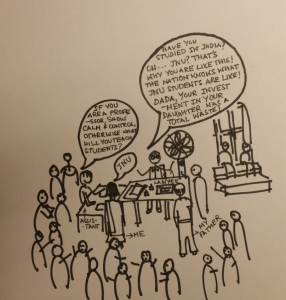

I am drawing a few stick figures below to explain this situation:

A graphical representation of the situation I was immersed in.

“I also went to JNU, I have four PhDs, I piss on your PhD”, he was screaming. My father is a seasoned, retired, government employee. He knew that in order to get anything done in the bureaucratic system here, one must ensure that the bureaucrat feels powerful. So, while I was getting into this full-blown screaming match, he tried to stop me from arguing. But when the lawyer repeatedly addressed him and told him that his “investment” in my education was a waste of his money, he said something that startled me too. Quite calmly he told the lawyer, “I don’t know how you raise your children, but my daughter is not a stock in the market. It was my duty to educate her; it was not an investment”.

On the one hand, this lawyer was screaming obscenities at me and educated women like me; on the other hand his assistant was challenging my capacity to handle a tricky situation calmly apparently in the interest of the future generation I will hone. “I will make sure you never get this paper, what will you do? Madam Professor… what power do you have?” Meanwhile, the crowd of dalals and notaries gathering around us were all saying things about “women these days”. I have never felt cornered like that in the twenty years or so that I have navigated the public spaces of Calcutta. I was about to cry and I did not want to cry.

I knew quite well that in a city where women are raped every other day and the report is carried in a corner of the 7th or 8th page, this was not a newsworthy story. But I decided I will threaten them. “I will call the media right now; I have friends in ABP Ananda (Bengali news channel). This city should know what happens in this local court”. As I said this, I also began to cry. Now, some men intervened and asked the lawyer to stop shouting. One of them pulled me and my father to a corner and assured us that they will ensure that the lawyer writes the report. I am not sure if this happened due to the fear of the media. Or maybe it was because a weeping woman, in this patriarchal order, is more acceptable as someone in need of protection and saving compared to an elite, adversarial screaming woman. “Syar eta ki hochche, meyechhele kadchhe kaajer jayegay? (Sir, what is happening? Why are womenfolk crying in our workplace?)”

I went and sat in the corner of a courtyard. I thought of our abstract feminist academic discourse in classrooms. I thought what happens to other women who have come here by themselves to get papers for jobs, property, births, marriages, divorces and such indispensable things. How many had to send their fathers, brothers, partners or drivers? I sat and wrote a Facebook message to everyone I knew in the media. Meanwhile, several men came up to me one by one and asked me not to go anywhere near the lawyer. He had finally relented and the letter was being drafted. “If you go there and sahib sees you, he will get angry again. And your work will not get done. Sit here! Don’t move”, I was warned.

I saw my father talking to this lawyer. Apparently out of the ₹2000 I paid to different people, he only got ₹ 30 while his stamp and signature were the only valid ones on the affidavit. That’s why he was angry, my father explained. When we went back together to the ‘foreigners department’ in the police headquarters, I felt they were quite relieved to see me with a male guardian. When I told them what happened, they laughed at me for not knowing that one should not pay more than ₹200 for an affidavit. My father said that he had warned me but I did not listen. Then I heard twice or thrice the officers telling each other my story, “Her father warned her, but she did not listen to her father…”

Remembering My Mother: Women Negotiating The System

My mother joined the Sales Tax Office as a lower division clerk; she retired as a gazetted Commercial Tax Officer in the state government. Because there was no one to look after me as a child at home, she used to take me to her workplace. I grew up listening to her colleagues who I called mashis (aunties) and mamas (uncles), eating ‘Bapuji’ cake from the canteen, and sleeping in wooden benches in the corners of the office. After this incident, I recalled how the gender dynamic in these offices closely matched that of my working class family. Men knew things and spoke with confidence about everything; women asked them how things were done “out in the world”. Men said things loudly; women were coy, coquettish, tactful, and quiet. The women in that office never claimed to be equal in their expertise to men even though they had the same rank. I remember my mother coming back from work one evening and complaining about how a young woman– who had joined as their boss straightaway by topping the civil service exam– had no respect for the “senior” male clerks. My mother rose in rank and became a boss. But she pretended that she was learning from her subordinates: older and younger men. She called it respect. Standing outside Bankshall court, it was suddenly clear what she meant by respect. She meant the coy, tactful, deferential tone that I have seen women picking up with men when they have to get things done at home and on the street.

I was told at one point that it was not my gender but my attitude which so enraged the lawyer. Be that as it may, I have no doubt in my mind that his deep insecurity about status, education and authority came from being a middle-aged man in a system which is under his control within the iron gates of Bankshall court but rapidly changing outside. A female client with money and social standing disturbs fundamental ideas about status, gender role and hierarchy in a sarkari office. I wonder what happens to brilliant women who compete in national or state level civil service examinations and end up in these offices.

This is a common, everyday experience for your typical ‘spoilt, Indian, modern woman’ who keeps ‘nagging’ for more autonomy, mobility and God forbid, even pleasure in the city. From the radical left to the right side of the political spectrum, from men’s rights activists to Dalit rights activists, the ‘spoilt, Indian, modern woman’ is criticized on many grounds: some blatantly misogynist, some nuanced and justified. But try telling us we have achieved enough the day advocates in local courts, like Sehgal in Pink, start mansplaining feminist ideals of claiming public space instead of asking us to go back to the kitchen.

Also Read: The Right To Walk: Women in Public Spaces

About the author(s)

Moumita is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oslo working on Hindu Nationalism, and Adivasi politics and religion. She is a visual studies scholar who has written about the clay-modelling industry of West Bengal. Here, she writes about women in different aspects of public life in India.

stunningly flawed. as a woman myself, i feel that the dictum ‘personal is political’ has become a blatant license for failed novelists and writers devoid of any talent – these constitute an apt description of this author. such superficially subjective account masquerading as the default document of the oppression of (even) ‘elite’ women in a patriarchal world dilutes both feminism and the art of writing. a random mix of self-pity and self-hatred can never result in coherent thought or good writing.

@soma: i’m sorry, but your response to this article is by no stretch of indulgence a hallmark of either coherent thought or good writing. rather than spew some random derogatory adjectives at a well-written and self-reflexive piece, it would have been more useful had you engaged with the ideas in it to tell readers precisely what you found objectionable in it!

(here comes the male arbiter)

sure, sir. the comment was not intended to carry any literary or theoretical form, the capacity for which may or may not reside in me. it was a polemical response.

there is nothing specifically bad, sir, in this article. it is as bad as any other content on the internet, otherwise than piracy. but who would not fancy a little bit of turd-mining, sir?

as far as broad agenda is concerned, the author is a sister, a comrade. but ‘no squabble in the war room’-approach (in the face of common enemy) is also sterile. we should split sorority hair.

a few axioms to sum up: 1. a serious article written by a self-proclaimed elite woman who is also a university-proclaimed scholar should not have a title beginning with ‘how i met’ or include the word ‘mansplaining’. 2. a serious article written by a self-proclaimed elite woman who is also a university-proclaimed scholar should have references to agnes varda or chantal akerman, not content-analysis of aniruddha roy chowdhury’s film. 3. a serious article written by a self-proclaimed elite woman who is also a university-proclaimed scholar should not include completely meaningless, unsubstantiated and brusque sentences like “from the radical left to the right side of the political spectrum, from men’s rights activists to Dalit rights activists, the ‘spoilt, Indian, modern woman’ is criticized on many grounds: some blatantly misogynist, some nuanced and justified.” 4. a serious article written by a self-proclaimed elite woman who is also a university-proclaimed scholar should exhibit that self-reflexive language does not – ever – read like a petition for social justice. 5. a serious article written by a self-proclaimed elite woman who is also a university-proclaimed scholar should be aware that such pertinent petitions for social justice are indeed being written – say, for example, the agricultural worker from bulandshahr who refused to withdraw her case against the many landowning men who raped her, men who then pinned her down and poured acid on her face, inside the administrative precincts. 6. a serious article written by a self-proclaimed elite woman who is also a university-proclaimed scholar should also remain confident that the previous axiom does not hold that her/our everyday grievances/humiliations do not count – but a merely straightforward documentary representation of her life, her father’s distilled wisdom, her mother’s difficult upward social mobility despite patriarchy is – to understate – entirely vapid (and may it remain so for her and her family, amen). 7. a serious article written by a self-proclaimed elite woman who is also a university-proclaimed scholar should then eschew the popular more confidently, be at peace with its author’s vanguard stature and become either a philosophical tract or a digestion/computation of more immense/varied data (studying cases pending in bankshal court where at least one interested party is a woman, for example) or an inventive short story or novella.

@ Soma Thanks for the close reading. Also, thanks for being the watchdog of the internet and the gate-keeper of feminism in general.

From what I gleaned from your long comment, it seems that you have certain ideas about what a “serious” academic article can be, say and study, about what exact ends self-reflexivity can lead to, and about what feminism can and cannot be. I disagree with all these ideas given that they sound little more than prejudices at this point.

This is a popular article. I have explicitly mentioned it is a personal and subjective narrative multiple times. It is listed in the “My Story” section. This is not research, neither does it claim so.

I could not overlook the irony in your critique of the term ‘mansplaining’ following your own caustic comments at a (presumably, might I add) “male arbiter”. I do not think feminism is or should be a sorority of “hair splitting” cis gendered sisters.

Next article, “How a feminist pissed on my feminism because I said I had a PhD”….

@moumita: it is not fair to reduce my entire response to your article to my jealousy (lack of phd) and prejudices (the contention that ‘subjective’ is not the same as ‘individual’ and that there should be artistic/philosophical constraints on diasporic self-anthropologisation). @feminisminindia: a website on feminism deleting angry responses to let the author have the last word is not fair, too. what kind of responses do you expect to self-indulgent sob stories that make up this section? or is it that only sanctioned authors can write personally and emotionally? this is so, so wack.