The practice of untouchability has been outlawed by Indian constitution under Article 17 and the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955. But laws are never a panacea for social ills and therefore the practice still continues in various forms. In November 2015, Indian Express reported that a village called Hajipur in Gujarat’s Patan district had separate anganwadis for Dalit children and Savarna Hindu children. Another report of January 2017 by the same publication said that 67 students of a government primary school skipped food prepared under mid-day meal scheme because the food was cooked by a Dalit woman.

The Hindu shastras divide Hindu society in four varnas — Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra. There was a section of society that was outside this fourfold varna system but was in an exploitative relationship with the caste Hindus and also faced many sanctions. This group has come to be known as Dalits. Caste Hindus considered them “impure” and hence people they could not come in contact with — the “untouchables”. This practice of untouchability was not limited only to interpersonal interaction but also extended to public spaces. Dalits could not enter temples, were forced to have their separate water bodies, their children had to sit separately in schools and so on. Mahad Satyagraha was one of the most important organised efforts under the leadership of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar to challenge these regressive customs of the caste Hindus.

Bombay Legislative Council had adopted a resolution moved by S.K. Bole on August 4, 1923. The Bole Resolution said, “The Council recommends the Untouchable Classes be allowed to use all public watering places, wells and dharmashalas which are built and maintained out of public funds or administered by bodies appointed by Government or created by statute, as well as public schools, courts, offices and dispensaries” (cited in Dr Ambedkar: Life and Mission by Dhananjay Keer).

Mahad Municipality, which was part of Bombay Province territory, had reaffirmed this resolution in 1924. However, the resolution remained on paper until Dr Ambedkar and his companions went to drink water from the Chavdar tank of Mahad on March 20, 1927.

Dr Ambedkar had gone to Mahad for a two-day conference organised by Kolaba District Depressed Classes on March 19–20, 1927 on the invitation of Ramachandra Babaji More. Dr Ambedkar presided over this conference, which was attended by thousands of delegates. The main agenda of the gathering was to raise awareness about the civil rights of Dalits. During the conference it was decided that the attendees would march to Chavdar tank and the “untouchables” will assert their moral and legal right to access a public water body. Talking about the importance of Chavdar tank, Dr Ambedkar says:

“The Untouchables, either for purposes of doing their shopping and also for the purpose of their duty as village servants, had to come to Mahad to deliver to the taluka officer either the correspondence sent by village officials or to pay Government revenue collected by village officials. The Chawdar tank was the only public tank from which an outsider could get water. But the Untouchables were not allowed to take water from this tank. The only source of water for the Untouchables was the well in the Untouchables quarters in the town of Mahad. This well was at some distance from the centre of the town. It was quite choked on account of its neglect by the Municipality” (“The Revolt of the Untouchables”, Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches, Vol 5).

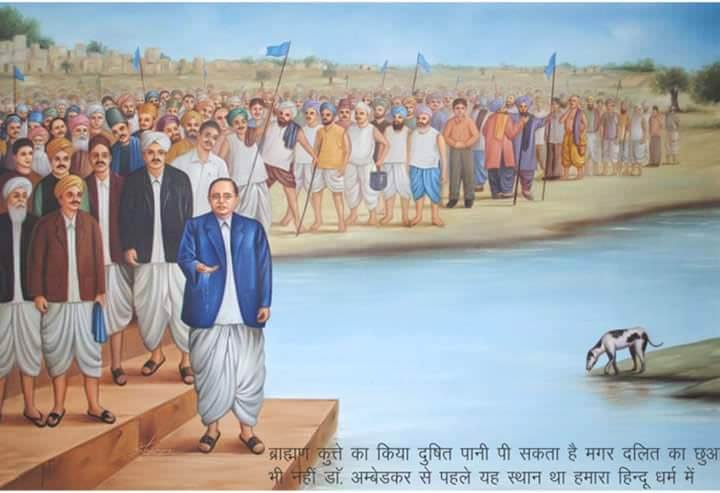

On March 20, Dr Ambedkar and his co-workers led a procession of 2,500 “untouchables” through main streets towards the Chavdar tank. Dr. Ambedkar took water from the tank and drank it. Others followed suit. This was known as the Mahad Satyagraha. Then everybody returned to the pandal. It was a peaceful protest but quite revolutionary in its implications.

Two hours after the event, caste Hindus raised a false rumour that the “untouchables” were also planning to enter the temple of Veereshwar. At this a large crowd of caste Hindus armed with bamboo sticks gathered at street corners. They dashed into the pandal. Many of the delegates were at that time scattered in small groups in the city. Some were busy packing and a few were taking their meals before dispersing for their villages. The majority of the delegates had by now left the town. The rowdy mob pounced upon the delegates in the pandal, knocked down their food in the dust, pounded their utensils and beat them.

They also sent messages to their henchmen to punish the delegates of the conference in their respective villages. In obedience, assaults were committed on a number of people either before or after they had reached their villages (“Mahad Satyagraha not for Water but to Establish Human Rights”, Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches, Volume 17, Part 1).

Caste Hindus of Mahad did not like Dr Ambedkar and his companions’ revolutionary act. They carried out a purification ritual to undo the “desecration”. Dr Ambedkar was so disgusted by this gesture, he and his comrades eventually went on to burn Manusmriti at the same spot later in the year (December 25, 1927).

Also read: Why Manusmriti Dahan Divas Is Still Relevant

Featured image source: Shreya Tingal/Feminism in India