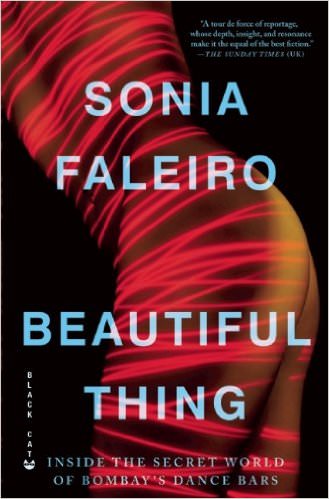

Title: Beautiful Thing: Inside the Secret World of Bombay’s Dance Bars.

Author: Sonia Faleiro

Genre: Non- Fiction

Beautiful Thing, by Sonia Faleiro, demonstrates through the story of Leela, a bar dancer in Bombay, how the bar dancing and sex work industry of Bombay thrives and sustains itself. As we know, legally, sex work is not illegal in India. However, related activities like setting up of a brothel, pimping and soliciting sex is. Faleiro demonstrates the inherent contradictions of this setup in her book that brilliantly reflects the thoughts, dreams and aspirations of Bombay’s bar dancers.

Beautiful Thing revolves around the life of Leela, the highest-paid bar dancer of a seedy Mumbai bar. Leela was punished by her father for being a “disobedient child” for refusing to star in child-porn clips, and was thus sold to a police officer. At the age of 13, she escaped from her house to Bombay in the hope of having a successful career. However, a woman who helped her was a brothel “madam” and it was here that Leela got her first job as a bar dancer and also all the power and money that she craved.

Faleiro narrates the life of bar dancers from their own perspectives, juxtaposing their aspirations and emotional dilemmas against the harsh reality of the society they live in; where their work is considered “dirty” and “immoral”. Due to the criminalisation of sex work in India, the women involved in this kind of work are not respected and are not granted protection under Indian law.

While reading this book, I had assumed that Leela would be unapologetic about the work that she did but I did see a few glimpses of “shame” associated with the kind of work she did. Bar dancers were quick to distance themselves from sex workers, Faleiro writes, “because selling sex wasn’t a bar dancer’s primary occupation and because when she did sell sex she did so quietly and most often under her own covers.”

So while most bar dancers did practice sex work from time to time, none of them readily admitted to it because it was perceived as a “wrong” work to be engaged in. To quote a passage from the book: “Although they all did it, no bar dancer ever admitted to the “galat kaam” (wrong work). the only answer to the question around it was- “main mar jaoongi but galat kaam kabhi nahin karoongi.” (I will die but I will not do wrong work) …The brazen one who admitted to it, it was said of her as a randi, a whore…”

There is undoubtedly a feminist spark in Faleiro’s portrayal of women in this book. One of the bar dancers, Anita, was raped repeatedly before the age of ten. She decides finally, “I decided that if this was going to keep happening to me, then at least I should profit from it, I should eat from it.”

One thing that I learnt from this book was that many young girls that are raped (even when it is by family members), are cast out by their own family and are then forced into the not-so-respectable occupation of a bar dancer which inevitably led to sex work as well.

The protagonist of the book, Leela, has no time for pity. She urges the author not to compare Leela’s life with that of hers, but with that of Leela’s mother, sisters and sisters-in-law. There is a passage in the book which makes us reflect on the bodily agency that Leela can exercise not only because she is financially independent but also because she is a woman who is not entrenched or tamed by the familial ties that her mother, sister and sisters-in-law are tied with. It is in this context that Leela says: “If my mother talks to a man who isn’t her son, brother or cousin, she will hear the sound of my father’s hand across her face, feel his fist against her breasts…If I don’t want to talk I say, “Get lost oye!”… Every life has its benefits. I make money and money gives me something my mother never had. Azaadi. Freedom. And if I have to dance for men so I can have it, okay then, I will dance for men.”

Leela thus clearly links her freedom and agency to act on her own terms with the economic independence that bar dancing affords her. While she does not look down upon her work, and cherishes the financial autonomy it brings her, she belies typically middle-class aspirations of marriage, housewifery and motherhood – knowing full well that no “decent” man will want her since she is not a “good” girl.

Beautiful Thing rightly unravels the tradition of marriage in India in which women are dependent on their husbands for clothing, food and shelter but hardly for love. She exposes the hypocrisy of marriage in the tales of middle class Maharashtrian housewives who let the local pimp and their girls in as soon as their husbands leave for work in order to exchange money and earn some money on the side.

Through Leela’s emotional negotiations with her family, Fareilo also tries to show the hypocrisy that is prevalent in every Indian family which values a boy child more than a girl child. It is in this context that Leela argues with her mother and questions her as to why she doesn’t love her more than her brother since she is the one who takes care of her and sees that she has all the access to the medical facilities that are required for her. She says, “…when I am the one who became a success and made money, makes money! Money like a man! No, no, more than a man! I’ll tell you why. Because they’re boys. And I’m a girl…The value of a boy is twice that of a girl – isn’t it so mummy, even if the boy is useless?”

The book ends when the bar where Leela works, ‘Night Lovers‘, shuts down because of the Maharashtra government’s ban on the dance bars in 2005, which was imposed in the name of immoral trafficking and to prevent prostitution in the state. The ban, however, did not affect dance performances in the luxury hotels, leading to a clear classist embargo on pleasure.

The end of the book really makes us question the “morality” of a professions such as bar dancing and sex work, because after the imposition of the ban, Leela is left with no choice but to leave the country and go to Dubai in hope for work. In a society where exists a hierarchy of work – for instance, where intellectual work is placed at the top, physical labour is seen as not “respectable” enough – sex work is not seen as merely work. It has moral connotations attached to it, since a woman’s sexuality is the last bastion of a community’s honour and cannot be freely given away. The distaste around sex work heightens the morally-tinted virgin-whore dichotomy, where the latter is seen as a threat to familial ties and the moral fibre of the society.

What this all-important “morality” fails to realise is that bar dancers and sex workers are also people who have families to feed and employ their body as a tool to earn money, just as manual and intellectual labour does. However, the free and fair rights of sex workers are often conflated with the coerced prostitution and trafficking of young girls, leading to all kinds of sex work being demonised.

About the author(s)

Pursuing Masters in Political Science from Delhi University. Trying to be the change I want to see .