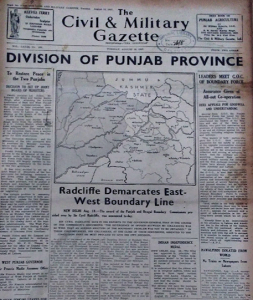

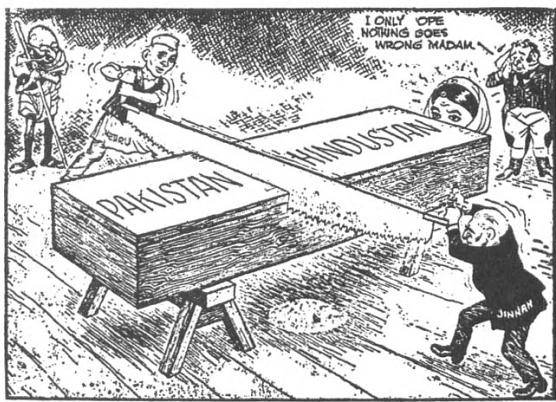

The ‘Great Divide‘ of British India and subsequent creation of the independent nation-states of India and Pakistan in 1947, and eventually Bangladesh in 1971, was a life-altering event for the millions who were displaced and forced to migrate. It was the biggest mass migration in the world of about 12 million people, with around 1 million dying in the process. About 75,000 women were thought to have been raped, abducted or killed during the whole ordeal. It was also recorded widely in both the Indian and international media, the celebratory news of independence as well as the horrors of partition.

For a long time, while studying Partition, the emphasis was on analysing or documenting the role of political figures, the events that led to the partition and during the partition. It was after the 1984 anti-Sikh riots that scholars and women activists started looking into the human suffering during the partition, and the harrowing experiences of women came to light.

The partition of Punjab into West (in Pakistan) and East (in India) Punjab experienced violence on an unprecedented scale because of the confusion around it, as well as the large population. Of the 12 million migrations, 10 million were from the Punjab region. Moreover, both governments could not have anticipated the escalation of communal violence to such a degree that it lasted from March to November 1947.

Violence Against Women

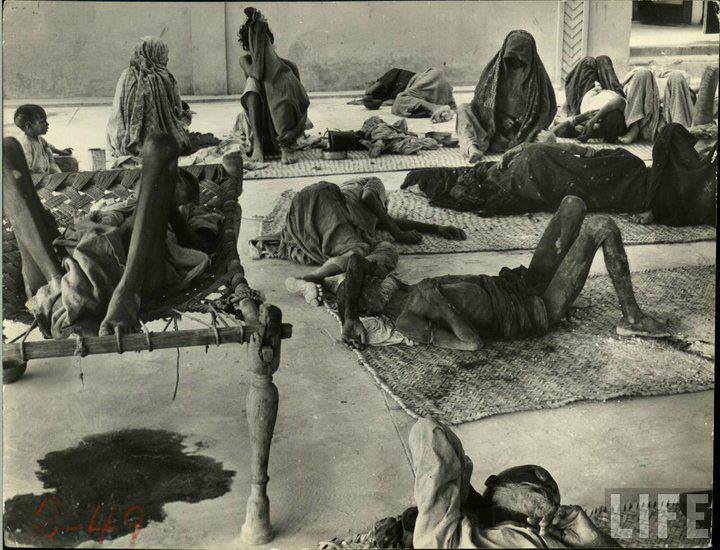

Women were subjected to various kinds of violence by different agents during the partition. Thousands of women, estimates range from 25,000 to 29,000 Hindu and Sikh women and 12,000 to 15,000 Muslim women, were abducted, raped, forced into marriage, forced to convert and killed, on both sides of the border.

Women were also mutilated, their breasts cut off, stripped naked and paraded down the streets, and their bodies carved with religious symbols of the ‘other‘ community. In his book Stern Reckoning, writing about his experiences as a Fact Finding Commission member, GD Khosla relates the instance of a young girl whose relations were made to stand in a circle and watch while she was raped by several men.

Incidents of such cruelty suggest how the women were reduced to their bodies, carrying the burden of the honour of the community, to be conquered, claimed or marked to attack that honour.

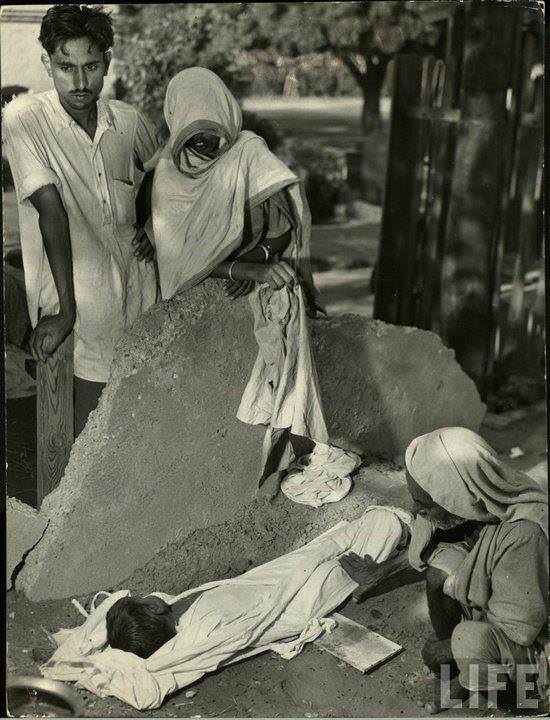

Violence was also inflicted on women by their men in the form of suicides they were coerced into, or killed in the name of honour. Some women committed suicide of their own volition to keep their ‘purity’ and were later glorified as ‘martyrs’. The mass suicides in Thoa Khalsa, Rawalpindi, with 90 women jumping in the well, was greatly publicised in the news. The Statesman in its report also compared this act to the Rajput tradition of Sati, thereby giving it the sanction of traditions.

Through the interview of one of the three survivors (Basant Kaur) of the Thoa Khalsa incident, Urvashi Butalia deconstructs the conventional view of women being always perceived as victims in an ethnic conflict. She argues that while some women were forced and compelled to die, if the accounts of the survivors are to be believed, some voluntarily took this decision.

While these women were conforming to the patriarchal notions of society of the honour of the community resting on the purity of the woman, they took the decision consciously, albeit for the community rather than their selves. The notion of men as protectors was also held by them, who preferred ‘sacrificing’ themselves when their men were unable to protect them from the enemy. Moreover, the act of voluntarily killing yourself and encouraging others is a type of violence too. Thus, she claims, women had varying experiences during the partition, depending on their position and assuming a perpetual non-violent victim position is a reductionist take on women’s histories.

Another kind of violence that women faced was inflicted by the State immediately after the violence during the partition. Many families had reported their family members, especially their women, as missing or abducted. The immense scale of such reports compelled the governments on both sides to act, and the task was carried out by the United Council for Relief and Welfare under Edwina Mountbatten, which made the list of missing persons and sent them to the local police station.

Abducted Persons Recovery and Restoration

In September 1947, the Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan met at Lahore and decided to start a program for recovering abducted women from both sides. On December 6, 1947, an Inter-Dominion Treaty was signed for this purpose, and the program was called Central Recovery Operation, comprising women social workers and police.

In 1949 the Abducted Persons (Recovery and Restoration) Act was also passed for the same. Under this act, a date was decided, and conversions and marriages of women after March 1, 1947, were not recognised, while these women were considered abducted persons. Through this Act, and it was the same for Pakistan, the State decided by itself on who was to be considered an ‘abducted person’ and the rights of the women themselves were completely disregarded. It highlights how the paternalistic state, as well as the patriarchal notion of a helpless woman, dictated the policies of the day, and the women had no independent agency over their families and citizenship.

This operation went on for 9 years after the partition, with around 22,000 Muslim women and 8000 Hindu and Sikh women being recovered. Certainly, many women were happy to be recovered, however, many were also forcefully taken by the officials. After being abducted, many women eventually adapted to their new circumstances, starting families with the men. Because of this program, their lives were uprooted once again. The social workers, too, though sympathising with the plight of these women, were bound by law to return them to their ‘natal’ countries, which was ultimately decided by their religion.

Butalia argues that, unlike the popular belief that the aggressors and abductors were always ‘outsiders’, there were many examples where women, of all ages, were abducted by men from their village. She claims that the social workers contended this by arguing that the women were abducted for various reasons, for instance, older women for their property. Thus, unlike in the dominant narrative of women’s experiences of partition, they were violated for many reasons and by their men as well.

There were also other reasons why women were reluctant to go back to their families or communities. Women were told exaggerated accounts of hardships in the ‘other’ country by their abductors. For instance, a statement by Lajwanti, a rescued woman, has been recorded in Muslim League Attack on Sikhs and Hindus in the Punjab 1947 in which she claimed that earlier she was reluctant to come because Abdul Ghani, her abductor, told her things like there was no food in India, all relations of Hindu women had been killed or even if they were alive they wouldn’t accept them. She was also told that the Indian army would kill the women the moment they stepped into India. Moreover, women themselves were scared of returning for fear of being ostracised because they were not ‘pure’ anymore.

The social workers on both sides also faced difficulties in finding women, as the local police accompanying them in the ‘other’ country would often warn the people, and the women would be hidden away. They had to resort to measures like disguises, false names and force to get their way. Butalia cites one incident from Kirpal Singh’s book The Partition of the Punjab, in which the policemen themselves raped a woman they had gone to recover.

Children of ‘Abducted’ Women

Regarding the children borne by the abducted women, as Veena Das maintains, the state refused to recognise them as legitimate since they were born of ‘wrong’ sexual unions. As a result, as Patel states, the women were separated from their children, and forcefully if they resisted, with the children being recognised as citizens of countries they were born in and staying with their fathers. She also gives the example of a woman who didn’t want to part from her child but had to for fear of not being accepted by her natal family.

The pregnant woman, on the other hand, had to either give their children up for adoption or go for abortion or ‘cleansing’ as it was called. Even though abortion was illegal in India at that time, the government financed mass abortions, especially for this purpose. Thus, such complex and life-altering decisions were taken without considering the feelings of or taking consent from the people they were made for.

While Muslim women were more easily accepted in Pakistan, in India, especially among Hindus, the issue of their ‘purity‘ became important. The children who were able to accompany their mothers became a constant reminder of the violation of the woman, and the mothers were given the option of giving them up for adoption or leaving the family.

Measures were also taken to encourage women’s acceptance in their families. Appeals were made by leaders assuring the people that these women were still ‘pure’. Pamphlets of the story of Sita’s abduction by Ravana were issued, showing how she stayed ‘pure’ even when away from her husband. Ashrams were set up in cities like Jalandhar, Amritsar, Karnal, and Delhi for the abducted women who were rejected by their families or whose families had not been found yet. Some of them were temporary arrangements for women until their family accepted them back, which, rarely happened.

Women who had to suffer such barbarity during the partition were again subjected to humiliation and rejection because they were not considered ‘pure’ anymore. As Butalia also states, the woman as a person was not significant here. It was the idea of the goodwill of the state as a protector of its women that took priority in these supposed programs of recovery and rehabilitation.

Other Effects Of Partition

Other, somewhat lesser, but significant in their way, effects on women’s lives were also there. Many were left abandoned and alone in life, due to partition. Partition had ruptured the lives of whole families, with every person needing to work for rebuilding that life. Women became social workers or had to engage in work, professional or otherwise, to support their families. Therefore, they had few means to pursue their desires or social activities like marriage. Sometimes, women were simply abandoned by their families for lack of a better alternative. On the other hand, as a result of this loneliness, conditions were also created for women to enter the public sphere, in a very unprecedented way.

Partition disrupted the lives of millions of people. Scholars claim that the Partition was not an event that occurred in 1947, but has been continuing in the form of contemporary politics in South Asia, and rightly so. Relations between India and Pakistan are heavily influenced by their history, and the Kashmir issue is still a bone of contention between the two. While the millions of people who suddenly became refugees, and their subsequent generations, have either deliberately erased it from their memories or are still living with bitter and often traumatic memories.

Literature on Partition

Many social workers have written memoirs describing their experiences and those of the abducted women, of their joy as well as reluctance at being ‘rescued’. Some among them include Anis Kidwai’s In the Shadow of Freedom (the original is in Urdu- Azadi Ki Chhao Mein), and Kamlaben Patel’s Torn from the Roots (the original is in Gujarati- Mool Suta Ukhde). There is also extensive regional literature on Partition.

Partition has also been extensively portrayed in films, novels and stories. Short stories like Thanda Gosht, Khol Do, Tassels by Saadat Hasan Manto, who also experienced the Partition, give a chilling account of the brutalities committed against women. There are also other works like Toba Tek Singh by Manto on Partition. Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan and Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children are internationally acclaimed novels dealing with the theme of Partition. Manju Kapur’s Difficult Daughters is the story of a young woman during the turmoil of Partition. Movies like Pinjar (adaptation of the novel of the same name by Amrita Pritam) and Khamosh Pani portray the violence women were subjected to during the Partition. Other famous movies include Garam Hawa, Earth (adaptation of Bapsi Sidhwa’s novel Cracking India/Ice Candy Man) and Begum Jaan (remake of the Bengali Rajkahini).

Also Read: Saadat Hasan Manto And His ‘Scandalous’ Women

References

- Butalia, Urvashi. The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Penguin Books India, 1998.

- Das, Veena. Critical Events: An Anthropological Perspective on Contemporary India. Delhi: Oxford Univ. Pr., 1998.

Featured image credit: Icy tales

About the author(s)

Himanshi is pursuing Masters in History and hopes to be a historian one day. She loves to read books, and even more to collect them. In her free time, she likes to explore historical haunts. Also, she is a foodie and spaghetti makes her heart race.

thanks a lot to give such intellectual and new overview about the partition specially in favor of women at that turmoil

A new vision and in depth study of history a gender perspective