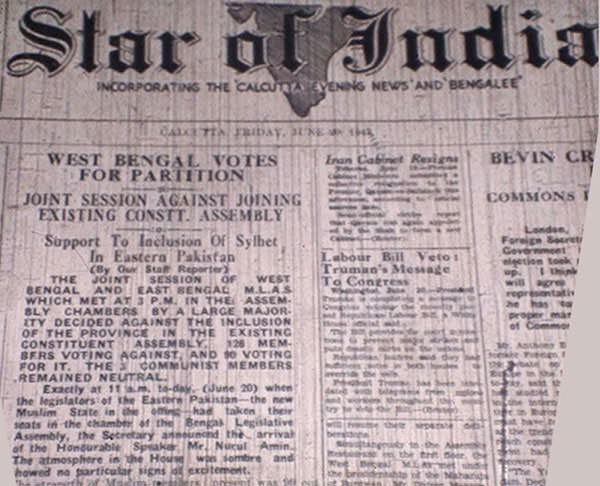

The Partition of undivided India into India and West and East Pakistan left a considerable impact on the whole of South Asia, the repercussions of which are still visible in its politics and societal attitudes. While the Partition on the Punjab side experienced an eruption of sudden violence and migration at an unimaginable scale, the east side witnessed a prolonged and torturous migration of mostly Hindus from East Bengal (East Pakistan, which became Bangladesh after 1971) to West Bengal in India. Bengal’s troubles did not end with the Partition and there were continuous migrations till 1971, while also continuing after that at a smaller scale.

Though there is plenty of literature in Bengali on the Partition, a concerning issue is the dearth of work done by scholars on the effects of Partition on the lives of women or refugees in general. Intellectuals like Urvashi Butalia also contend that there has been a huge gap in the scholarly documentation of the experience of people during the Partition in the Bengal region, with the major works being produced only now in the early 2000s.

The communal violence in the Bengal region started in October-November 1946 with the Noakhali riots and the women had to bear the brunt, becoming victims of rape, abduction, and forced conversion and marriage. Some women were also simply deserted later by their families on account of being pregnant as a result of rape or being ‘impure’.

Migrations to West Bengal

The slow process of migration was also adversely affected by the rehabilitation policies of the government. With the continuous influx of migrants from East Bengal even after decades of Partition, the West Bengal government came under increasing pressure from the Indian central government to round up the Rehabilitation Ministry to discourage further migrations.

However, the process was not carried out considering the conditions and needs of the refugees themselves, resulting in a half-hearted attempt at their rehabilitation. After discussions, it was decided that the migrants would be divided into three groups.

1. Migration occurring between October 1946 and March 1958 was termed ‘old migration’, with the migrants being eligible for government doles and rehabilitation, though more than half of them didn’t receive any assistance.

2. The second category consisted of migrations between April 1958 and December 1963, with the migrants being called ‘in-between migrants’. These migrants were not given any rehabilitation or financial assistance as the government believed them to be motivated by the pittance given out to them to shift their home and hearth to West Bengal.

3. The last category was that of ‘new migrants’ comprising of people migrating from 1963 to the 1970s. They were eligible for rehabilitation only if they sought occupation outside the state of West Bengal, while those who stayed became ineligible. These policies highlight the attitude of the government towards the refugees, who the government felt were mostly motivated by financial incentives, ignoring their plight.

Moreover, while in Punjab the immense scale of the violence had forced the government to take action and provide rehabilitation, in Bengal, the facilities, when provided, were very poorly organised.

Status of Rehabilitation Facilities

Ashoka Gupta, one of the social workers working for the rehabilitation of refugees, went to the Punjab camps in 1955 and pointed out the neglect of the Bengal camps. She submitted a report to the government according to which the doles for women in Bengal were much less than those in Punjab, there were also no separate women’s homes and latrines as well as no training centres to help them stand on their own. Later, six homes for women, six women’s camps, four mixed Permanent Liability (PL, one of the various types of camps) camps and five women’s training centres were established in West Bengal.

However, the women’s conditions in the rehabilitation camps and homes were deplorable. The PL camps, which have survived well into the 21st century, were again of three types, of which the ‘Complete Permanent Liability’ category consisted of people who had to fully depend on the government for their survival. These included old people and people with disability or infirmity.

Through the interviews of the inmates of PL camps, Subhasri Ghosh and Debjani Dutta highlight the plight of inmates that has continued for decades after Partition. While earlier many women staged protests demanding better facilities and to be rehabilitated, now many have accepted the camps as their permanent residence and live on the mercy of the state, while some still long for a family and to be rehabilitated to a ‘home’.

However, as Jasodhara Bagchi and Subhoranjan Dasgupta have argued, the East Bengali woman was not only a victimized recipient of her circumstances but also triumphed through her trauma. These women changed the social reality of West Bengal and became the inspiration for other women by coming out in the public sphere.

The hardships of Partition had left many women alone, with their husbands. The women, who had earlier been confined to their homes, were now compelled to enter the public sphere and earn a living to support their families or themselves. Rachel Weber, however, maintains that it was not that women were relieved of their domestic roles, but that domesticity was now expanded to include political, economic and social spheres.

However, Dasgupta argues that the reality was more complex than a simple expansion of domesticity. The women’s lives, including their families and relations, but also personal experiences and emotions, were affected by the Partition and braving to support their families in such traumatic situations was also a result of their determination along with necessity. Their jobs ranged from actresses, nurses, teachers, to bidi rollers and mill workers.

Economic independence also paved the way for women to take social and political decisions. Because of the inadequate rehabilitation provisions for the refugees, the refugee question became an important part of West Bengal politics. The refugees on their part were involved in a prolonged struggle demanding better rehabilitation, compensation, employment and franchise, and women stood shoulder to shoulder to their male counterparts in these protests.

The Communist Party of India (CPI) also played a significant part by spearheading many of the refugee protest movements. The women were especially supportive of CPI as along with their demands as refugees, it fought for their rights as women. By 1955, CPI had collected 14,102 signatures demanding employment for women in the government sector; it also fought for grants of marriage for girls and remarriage for widows, as well as the passing of the bill giving equal rights to inheritance to Hindu women in 1950.

These developments also have negative effects, to some extent, on the East Bengali women. On the one hand refugee women were thrown into completely different surroundings, from lush green countrysides where their life comprised mainly of the inner confines of their home to a crowded city where they had to start from scratch and take the responsibility of their families; on the other, they were not treated on par with the West Bengalis and the men, increasingly resulting in their alienation.

Partition also altered the lives of women who belonged to the minority community and did not migrate. Syed Tanveer Nasreen, through interviews with the women in two villages of Burdwan district in West Bengal, shows the trauma the Muslim women suffered and continue to suffer. The women lost their men and were reluctant and fearful to talk about sensitive details. She argues that the silences and the act of narration also highlighted their pain at recounting the incidents. She goes on to add that while the subsequent generation did not have a first-hand experience of a communal riot, they were still very much affected by the stories and experiences of the older generation on a personal level, thereby concluding that the trauma travels through generations.

Thus, Partition was a life-changing event for many women who suffered brutalities at the hands of men, were uprooted from their homes and lives, thrown into an unknown world or completely isolated and alienated from social life, and most importantly, successfully adapted to their difficult circumstances.

Literature on Partition

The theme of Partition has been greatly influential in defining the history, culture and social reality of the Bengal region on both sides of the Radcliffe line. It has also left a permanent impression on Bengali literature, being portrayed exhaustively in films, books, plays, and short stories, and continues to capture the imagination of many people.

The River Churning (Epar Ganga Opar Ganga in Bengali) by Jyotirmoyee Devi vividly portrays the tribulations of women during the division. There are innumerable short stories like Riot by Ishaq Chakhari, Hearth and Home by Hasan Azizul Haq and The Woman Who Sold Wares by Samaresh Basu.

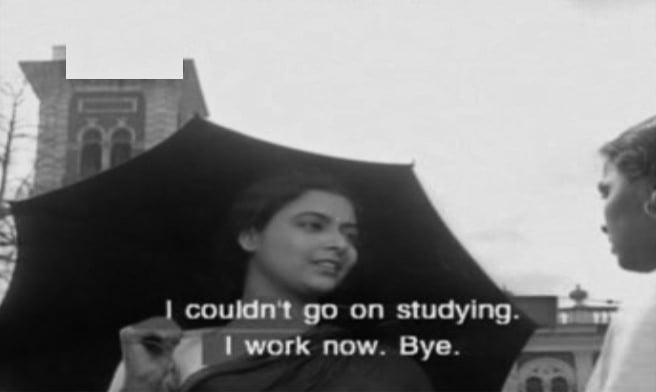

In films, Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar stars Madhabi Mukherjee, a refugee woman who went on to become a leading Bengali actress, in the 1950s when women in Bengal were gradually entering the public sphere as breadwinners of their families. Meghe Dhaka Tara, based on the novel of the same name by Shaktipada Rajguru, details the effects of partition on the lives of refugees. It forms part of a trilogy, with other movies being Komal Gandhar and Subarnarekha.

Also read: The Partition Of Punjab: A Tale Of Violation Of Women’s Rights

References

- Bagchi, Jasodhara, and Subhoranjan Dasgupta, eds. The Trauma and the Triumph: Gender and Partition in Eastern India. Vol. 2. Calcutta: Stree, 2009.

- Guha-Choudhury, Archit Basu. Engendered Freedom: Partition and East Bengali Migrant Women. Economic and Political Weekly 44, no. 49 (2009): 66-69.

- Sengupta, Anwesha. Looking Back at Partition and Women: A Factsheet. South Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, Vol. 4, No. 1: Summer 2012

Featured Image Credit: 21st February morning, 1953—female students of Dhaka University, festoons in hand in the procession via Wikimedia Commons.

About the author(s)

Himanshi is pursuing Masters in History and hopes to be a historian one day. She loves to read books, and even more to collect them. In her free time, she likes to explore historical haunts. Also, she is a foodie and spaghetti makes her heart race.