Posted by Madhura Chakraborty and Shradha Shreejaya

Caught between the expense of sanitary napkins and the stigma of menstrual blood, rural women are left without viable, hygienic options and those suffering from reproductive tract infections are often led to believe that hysterectomy is their only option.

At the stroke of midnight on July 1, the Indian government rolled out what is being touted as the biggest tax reform in 70 years of independence — the Goods and Services Tax (GST), an indirect tax applicable throughout India that aims to replace multiple taxes levied by the state and central governments. With this, menstrual hygiene products will be taxed under the same category as other ‘luxury’ commodities, while vermillion (applied to the forehead of Hindu women to indicate married status), mangalsutra (necklace worn by married women) and bangles not made out of precious metal (also a sign of marriage) will not be taxed. If this was a move to appease women, it backfired massively. There has been a surge in social media articles and online petitions regarding the taxing of sanitary napkins.

Women students in Thiruvananthapuram even mailed crate loads of sanitary napkins with the message ‘bleed without fear, bleed without tax’ to the finance minister. While the mainstream media focused on the women from urban, middle class taking to the social media to air their grievances, voices of rural women remain unheard.

I cannot afford to use sanitary napkins every time. It’s expensive.

“When I have to go far or go for an exam I use sanitary napkins but at home I use cloth. This is because I cannot afford to use sanitary napkins every time. It’s expensive,” says Sonam Kumari, a high school student in a remote, border village of Champaran district of Bihar who also works a tailoring job from home. “It’s good to use Stayfree for hygiene and it comes in a packet so it is easy to carry around,” her neighbour Kismat adds. While the National Family Health Survey(2015-16) reveals that 48% rural women (and 80% adolescent girls) use sanitary napkins, many cannot afford it.

“On the one hand the government promotes ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’ (Save and Educate the Girl Child), but on the other, it is so regressive that it forgets that each girl child needs access to menstrual hygiene products every month. The 12% GST on menstrual hygiene products denies the physical realities of bodies and the needs of almost half the country’s population”, says Nivedita from Goonj, an NGO that works with the women in rural Bihar.

Along with costs that are prohibitively expensive for some women, taboos and lack of health information, result in women still using dirty rags during their menstrual cycle, despite most of them having scope for accessing clean cotton cloth. “There is no proper advice or education given to these girls or women in villages about clean cloth usage. Their mindset is that periods is a dirty process and why waste money by purchasing clean cloth or sanitary napkins that is only to be thrown away, ” says SM Shabir, a medical practitioner from Bihar. As conversations with women from rural Bihar reveal, the stigma associated with periods means that the women have to hide the cloth they use for periods and clean and dry it away from public eye, often in very unsanitary conditions.

Pieces of cloth used for periods are often left out to dry in unhygienic conditions.

This if left unattended can lead to vaginal infections. An even more shocking picture emerges from the testimony of Anita Devi from another part of Bihar. Still in her 30s, she has undergone a complete hysterectomy. The doctors recommended it because she had severe reproductive tract infection. Doctors believe this is because she used dirty cloth for her periods. She still uses cloth for her periods but clearly says “If I could afford it, I would prefer to use sanitary napkins. I know several other women who had to undergo hysterectomies.” But is hysterectomy even the right intervention in such cases?

There has been a steep rise in the number of hysterectomies performed on women in rural India. Reports indicate that the procedures, mostly performed on women between age groups 30-35 years, are mostly unnecessary. Scams in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Karnataka over such malpractices have been making rounds in media since 2010. Dr. Meenakshi Bharat, a leading gynaecologist from Bangalore, explains that sanitary napkins do not prevent infections that are otherwise caused by Uterine Tract Infections (UTIs) or Reproductive Tract Infections (RTIs). Neither should it lead to hysterectomy solely on the basis of infection, unless the condition is untreated for fairly long periods.

The idea of sanitary napkins as the only ‘proper’ way to manage menstruation, was promoted from the 60s by corporate actors in India.

Most importantly, women think that their health issues can be solved only by using sanitary napkins or getting the hysterectomy. But this is not the overall picture. The idea of sanitary napkins as the only ‘proper’ way to manage menstruation, was promoted from the 60s by corporate actors in India. Even today there are 4 large multinational corporations that manage the entire sanitary napkins market. Advertisements for the products repeatedly highlight ‘hygiene’, ‘comfort’, ‘fresh-smelling’ thereby promoting the idea that menstrual blood is dirty and prone to lead to diseases and should be hidden (absorbed).

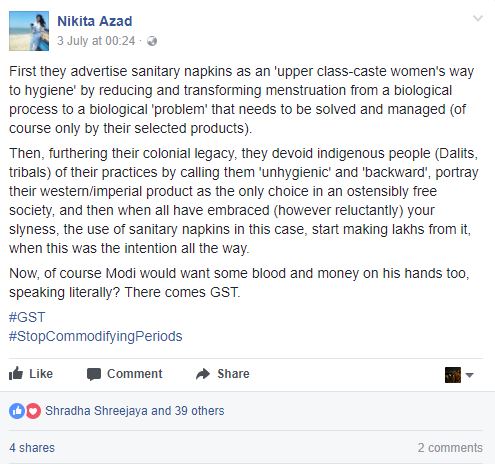

As Nikita Azad from the #HappytoBleed campaign aptly puts it across through her Facebook post, the corporate way has been to transform periods into a problem with its attendant discomforts and embarrassment (adding to the stigma) and marketing their products as the solution to said problems for upper class/caste women. Along with this, traditional menstruation management methods have been branded as backward and unhygienic.

With traditional roles of women transforming, and younger women going out more for work/education, most of them are only aware of sanitary napkins and think of them as the sole means for healthy menstrual care. Multinational corporations selling sanitary napkins have zero accountability to help the local bodies in sanitary waste disposal, despite mandates in Solid Waste Management Rules 2016. Sanitary napkins that are made of 95% plastic components are difficult to recycle with any other waste stream. At least in urban India, conversations around alternative menstrual hygiene products like cloth pads and menstrual cups are growing, keeping in mind that sanitary napkins in themselves pose disposal issues and health risks that are not widely known.

Also read: #ThePadEffect: Re-valuing Menstruation

In coming days we will find out if the product brands, mostly owned by multinational corporations, will hike their price to make up for increased taxes. What is certain is that ultimately women, particularly poorer women without access to adequate information or financial resources, will be the losers. In a country of paradoxes, we now face a question that brings the right to life at cross roads with larger issues of sustainability. Meanwhile, young girls like the ones in Champaran are left in the lurch – stigmatised for their natural body processes and caught between the ridiculous government taxes and corporate interests.

About the author(s)

Video Volunteers works to centre the lived experience of marginalised communities in public discourse and decision-making. Over the past 20 years, we’ve supported community-led reporting models in India and globally, enabling people to document issues affecting their lives and push for accountability. In India, our network of Community Content Creators has produced over 18,000 videos on local governance and social justice issues, contributing to more than 3,200 documented resolutions and impacting over 42 million people. Our work focuses on strengthening accountability, amplifying citizen voice, and using accessible technology to make institutions more responsive.