Posted by Renu Dhole

Angela Saini’s much talked-about book Inferior: How Science got Women Wrong is a thumping validation of all feminist epistemological questioning of Science and its claim to objectivity, neutrality and empirical truth.

By now, “Sex is biological. Gender is a social construct,” has safely entered mainstream consciousness. But the idea that sex itself is a social construct (argued by feminists like Judith Butler) and that sexual difference (like racism) was sought and used by science in a historical context still is met with resistance.

It still requires us to pause and absorb that maybe, the need to point out ‘sexual difference’ amongst other differences between human beings, as the most defining between men and women was politically-motivated. Science’s claim to objectivity and universal ‘truth’ has stood challenged from feminists forever, but it is the young British science journalist’s book that has shown up the bias inherent in scientific research from up close. Here, Saini talks to us about how medical science hasn’t given period pain the significance it deserves, but that there may be hope with more and more women researchers putting it on the agenda.

“Few people suffer from debilitating pain without anyone knowing about it. Yet I have, and I do. There’s a small ridge along my scalp which traces the stitches I received as a teenager when I passed out from period pain, hitting my head on the hard stone floor of the school’s physics laboratory. My monthly pain can still curl me into a ball, although these days I manage it well with delicately timed doses of ibuprofen. I do this all quietly, without anyone knowing. And I maintain this silence because, of course, that’s how society prefers its menstruating women,” she writes of her own experience in the upcoming issue of New Humanist magazine.

Shame, stigma, impurity – menstruation has always been surrounded by these cultural notions. What Saini argues is that, perhaps, this silence on the issue has extended to science itself, with the medical profession and research weighing menstrual problems women face all too lightly. Shedding some important light on the period leave debate that is a part of public discourse now, with many voices arguing against ‘special concessions’ to women based on their gender, Saini says in an e-interview with us, “If women do need or want to (take leave on the first day of period), workplaces need to accommodate that. If a man was experiencing debilitating pain for any reason, he would likely take a day off work. I find it odd that we often treat period pain as something women should absorb silently without complaint. But this also speaks to the fact that many workplace practices are designed with men in mind, not women.”

Also read: Who Gets to Decide For Or Against Menstrual Leaves?

The silent relegation of menstruation to the margins for most of history, Saini says in New Humanist, rendered it one of the least understood medical issues. “Even now, science has a fairly weak understanding of why women suffer period pain and pre-menstrual tension, and even fewer answers for how to manage it. A professor of reproductive health at University College London, John Guillebaud, told reporters at online magazine Quartz in 2016 that cramps can be almost as painful as having a heart attack. Yet by his own admission, medics have failed to give the problem the prominence it deserves,” she writes. Remember the time your doc dismissed your menstrual pain as a ‘women’s lot’? Well, probably medical science itself needs to know better.

This forms the crux of Saini’s book. Science has failed women in many ways because well, most scientists were men (white) and the standards they set coalesced with their masculine worldview. Women, their lives and problems, have naturally found very little voice in a discipline largely dominated by the concerns of men. “Periods are a perfect case in point. It’s no surprise that menstruation was ignored for so long when men didn’t experience it. It’s only fairly recently that women’s health has soared up the agenda. Until a few years ago, it was routine for women not even to be included in clinical studies for new drugs. Thanks to years of dedicated activism, mainly on the part of female health campaigners in the United States, this is no longer the case,” her article in the New Humanist. (However, including women may not always yield feminist results, Saini agrees when we point out. “I don’t think women can’t be sexist. Of course they can. But if science better represents the diversity of people out in the world, there is less chance of prejudice and bias within the system.”).

Just like science, workplaces were designed as per the needs of the male workforce. So women’s sexuality, their reproductive cycle, remain incongruous to the way our workplaces function. Saini tells us, “Most women around the world work, and they always have done. The difference, though, is in the work they tend to do. It tends to be lower-paid, lower-valued work. These are environments in which their personal needs are often overlooked. Menstruation, childbirth and motherhood are often treated as annoyances on the part of employers. They simply don’t care – women are expected to press on regardless of what their bodies need. Industries and work environments built around women’s needs would look very different, but we haven’t built them yet.”

In today’s corporatized work cultures, where women are making tough choices to stay in the game, many women at the top fear this period leave debate will just give sexist workplaces a reason to further devalue the ‘weaker sex’. “The idea of women being the ‘weaker sex’ is laughable. Women are better survivors, more robust and resilient than men. We often take on the bigger burden of physical work when childcare and housework is included in the calculation. We need to work together so that it is not men making the decisions about how workplaces should look, but us. Women in senior positions need to promote more women, support more women and not be afraid of feminising workplaces. Workplaces need to be feminised to take into account our demands,” Saini says.

Also read: #FOPLeave: What Does Menstrual Leave Mean For Working Women?

While the period leave debate continues to open inherently sexist workplaces up for investigation, it is perhaps important to note that a very small percentage of women in India actually work in organised, formal sector. At a time when women’s bodies are receiving more medical attention than ever (they’ve always been treated as faceless receivers of reproductive policies and healthcare), splitting open the very homogenised category of ‘women’ to see which women are we really talking about is well in order. Would our maids be granted the same right of period leave we ask for ourselves as women? That’s the question we need to ask ourselves.

Renu Deshpande-Dhole is a freelance journalist based in Pune.

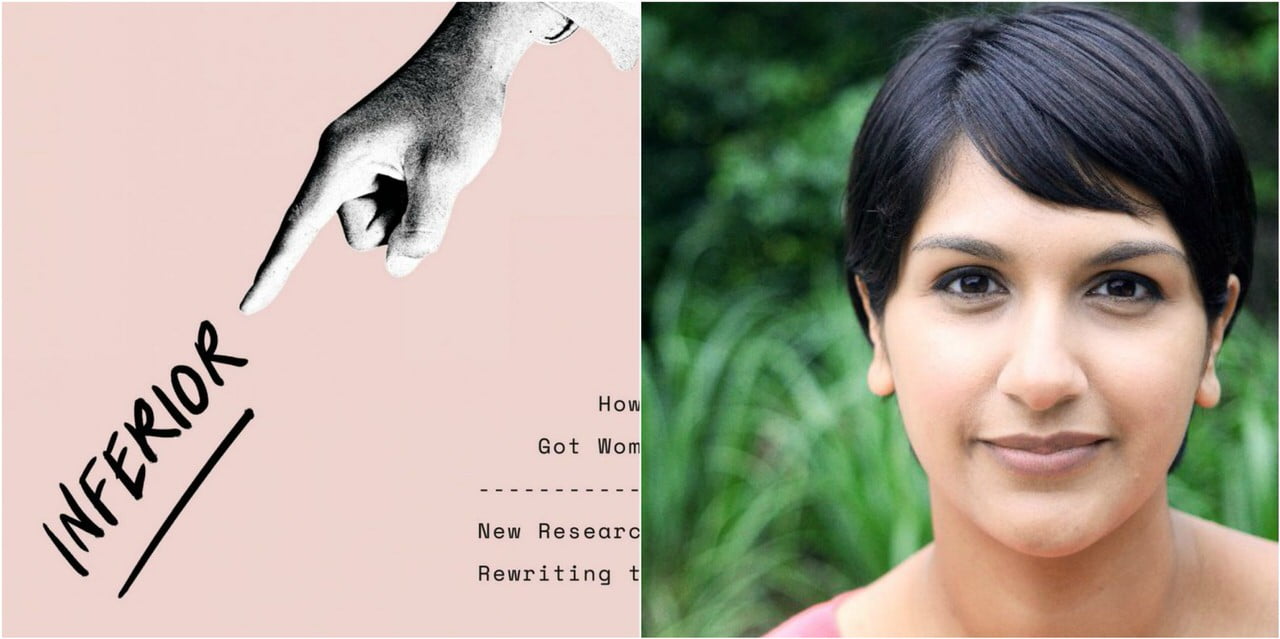

Featured Image Credit: Left: Cover of Inferior: How Science got Women Wrong; Right: Angela Saini

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.