Posted by Madhura Chakraborty

From tax reforms to Bollywood movie tropes to everyday realities – there is no escaping the symbols of marriage that only apply to women.

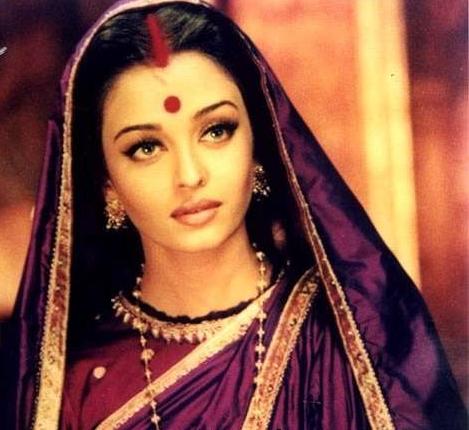

Applied to the parting in a married Hindu woman’s hair, sindoor is a symbol of her ‘blessed’ marital status. If Bollywood is to be believed, it is the most glorious symbol of success in life that any woman can aspire to. There are an array of films with sindoor and suhagan (married woman whose husband is still alive) as part of their titles and the heroines cry with happiness whenever the hero fills their hair with red powder and in some cases, even blood (!). In a parodic clip from the film Om Shanti Om, which has since become iconic, the heroine Shantipriya, extols the virtues of vermillion: it is God’s blessing, a married woman’s crowning glory, everything a woman has always dreamt of.

Women who play villains in TV soaps and Bollywood films are often marked by their refusal to conform to the saintly sindoor sisterhood of long suffering, self-sacrificing sanskari Hindu naari who give it all up for their husbands and their families.

The good wife

The vamp

But this is not just a ridiculous movie trope. In rural Jharkhand Rita Devi has developed skin infections from applying sindoor in her parting but she feels she cannot stop. “If I didn’t apply sindoor, it would feel strange, I would feel like a widow. It wouldn’t feel good. In earlier times it was believed that sindoor must be applied for the husband’s long life. I also fear my husband may suffer harm if I don’t apply sindoor.” Similarly, Amrita, who works for Video Volunteers and never wears sindoor, occasionally applies it just to get away from tiresome questioning. “I wore it at my cousin’s wedding just to stop people from making an issue out of it,” she says. There’s clearly immense societal pressure on women to conform to the role of the ‘good wife’ not just in action but also in appearance.

Community Correspondent Bharati Kumari asks men in Rita Devi’s village about the significance of sindoor. “What are you trying to say? If they don’t use sindoor how can one tell married and unmarried women apart?”, asks a seemingly annoyed Sunil Bhuiyan. He laughs innocuously when asked how unmarried men can be distinguished from their married counterparts — apart from the obvious imbalance in the need to determine the marital status of women, there is no such pressure for men. But as another woman’s response reveals, the misogyny is internalised. “When you have sindoor and go outdoors, you don’t face any (street sexual) harassment because it shows you are married. Single women get harassed all the time,” asserts Rekha Devi when asked about the significance of sindoor as a symbol of marriage.

The implication is obviously that a married woman is ‘owned’, property of another man. Her sindoor, red bangles, mangalsutra all indicate this status. Men obviously do not need these markers to indicate their marital status because they cannot be owned – they don’t change their surnames or residences post marriage either. A woman is groomed to become a wife, nothing else and widowhood is the worst fate that could befall women. Not only sindoor, a whole host of rituals are designed to pray for the husband’s long life. Needless to say while women fast and pray to lengthen their spouses’ lives, no such rituals are performed for them.

And make no mistake – this is not just about poor, uneducated rural women. It is equally the fate that befalls urban women. One look at the matrimonial columns will reveal men are looking for brides about half their age, ‘fair’, ‘convent-educated’ and ‘homely’. Advertisements looking for grooms equally are always looking for professional, ‘well-established’ men. Women’s careers are marriage and the sindoor on the forehead signals they have succeeded in landing that most coveted ‘job position’.

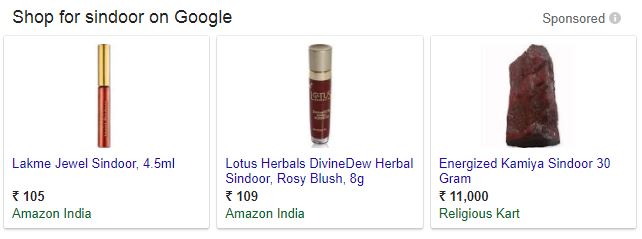

But what exactly is the sindoor and how does something oh so pious causes skin infections? Traditionally, sindoor, apparently known as kumkuma is mostly turmeric – definitely not red. The red sindoor is mostly vermillion, a derivative of cinnabar which is a naturally occurring form of mercury sulfide. Sometimes, red lead is also added. Heavy metals are known carcinogens. But fear not, if you’re rich you can buy sindoor in all shades of ‘herbal’ and ‘natural’.

Screengrab of sponsored results from Google when you search for ‘sindoor’.

Interestingly enough, under the new Goods and Services Tax, the government has seen fit to list all symbols of womanly virtue – sindoor, mangalsutra, bangles – under the tax free category. Menstrual hygiene products, on the other hand, attract a tax of 12% to 14%. The government clearly has its priorities sorted: after all the Bhartiya naari can do without clean napkins and tampons but clearly cannot do without something as indispensable as vermillion.

Of course, netizens cannot be left far behind – the fake science of justifying regressive patriarchal mores has embraced sindoor, mehendi, mangalsutra with enthusiasm. One article claims that there is an innate ‘science’ to applying sindoor which should be applied ‘upto the pituitary gland’ to remove stress. It also assures those who might be worried about heavy metal toxicity (silly women!) that mercury controls blood pressure and ‘activates sexual drive’ which is also why widows should not apply sindoor. Never mind that widows might also suffer from stress. Clearly women should all be monogamous and widowhood is the end of one’s sex life.

The article then waxes lyrical about the virtues of wearing bangles: it increases blood circulation and apparently ‘electricity passing out through outer skin is again reverted to one’s own body because of the ring shaped bangles.’ Who needs equality when you have ‘science’ supporting discrimination.

Patriarchy is a many-headed beast that coerces women to internalise misogynist symbols, compels them to and makes them feel good about being virtuous. It also marks those who dare to question such mores as ‘bad girls’. It’s time we stopped rationalising and upholding discrimination through official policies, private practices and fake science.

About the author(s)

Video Volunteers works to centre the lived experience of marginalised communities in public discourse and decision-making. Over the past 20 years, we’ve supported community-led reporting models in India and globally, enabling people to document issues affecting their lives and push for accountability. In India, our network of Community Content Creators has produced over 18,000 videos on local governance and social justice issues, contributing to more than 3,200 documented resolutions and impacting over 42 million people. Our work focuses on strengthening accountability, amplifying citizen voice, and using accessible technology to make institutions more responsive.