In the wake of the recent protest that has sparked off in Hindu College – Hostel Fees Must Fall, students asserted that they will not allow the women’s hostel which is built on government land to be run like a private PGs. The women’s hostel fee is twice as much as men’s, which is what the students have been protesting. Despite the student’s agitation and repeated questions being asked to the administration, it has failed to provide a reasonable justification for high fee, arbitrary rules and non transparent admission procedure into the Women’s hostel.

In her response to the Delhi Commission of Women (DCW) summon orders, the Principal of Hindu College said that the women’s hostel fees was higher because of lack of funds from the University Grants Commission (UGC). However it has to be stressed here that the college administration had lapsed on a fund of 82 lakhs in March 2012, which had been sanctioned by UGC. The Principal also went onto to claim that the hostel for women was expensive because of the ‘state of the art’ facilities and the infrastructure it provides. It must be noted here that this is the same hostel which didn’t even have a Sewage Treatment Plant until 2017 and has the capacity to contain only 156 women, that too on a twin-sharing basis, while the boys’ hostel has 119 rooms.

The women’s hostel fee is twice as much as the men’s hostel.

The whispers and sounds in the corridors of Hindu College expressed a divided opinion on the matter. Students were heard talking about how it was easy for some of them to ‘afford’ hostel against those who ‘couldn’t afford’ it. This logic shifts the focus away from the lack of the University and projects it onto students, who have been systematically made to feel like outsiders.

Clearly, the question isn’t about affordability, as the University is no market-place where Adam Smith’s invisible hand has a role to play in fee hike. Rather it is about reimagining the University which should ideally be able to set an upper limit to hostel fees, taking into consideration the various socio-politico-economic needs of students. The only thing that the University cannot ‘afford’ is to be ‘exclusive’ even as it rests on multiple layers of exclusion!

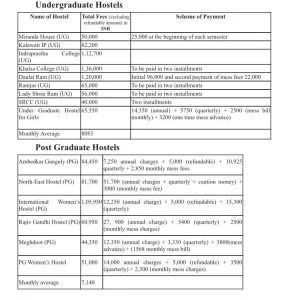

The Hindu College protests have helped us open the registers of institutional sexism only to find out that what Hindu College is doing is nothing out of the ordinary. In an interesting report compiled by the autonomous women’s movement, Pinjra Tod, they had conducted a study on hostel fees paid for ten months in 13 main undergraduate hostels and 12 main postgraduate hostels of Delhi University in the month of November 2015.

The Delhi Commission for Women (DCW) on 7th May 2016 responded to the complaint by issuing notices to all 23 registered universities in Delhi. Separate notices were sent to all undergraduate colleges under Delhi University which have women’s hostels, demanding information about their hostel fee structures. In their report, Pinjra Tod lays down a complete break down of the hostel fees as on November 2015, across different hostels in Delhi University. The fee structure has only gone up since.

Details of Accommodation Cost for Women in DU Hostels for 10 months, as on November’15 in the report by Pinjra Tod

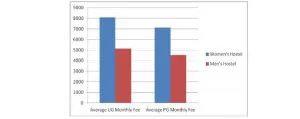

Their findings revealed an outrageous practice of gender discrimination with regard to hostel fees in Delhi University, which further translates into a direct deprivation of equal academic opportunity for women. The monthly average hostel fee for men and women, Pinjra Tod found that the University forces women students to pay ₹2,958 more for undergraduates, and ₹2,614 more for postgraduates, every month which then adds up to being ₹29,580 and ₹26,140 over the next 10 months of the academic year!

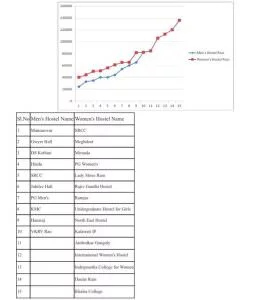

It was also seen that the men’s hostel with the lowest fees was Mansarovar postgraduate hostel at ₹24,295, whereas the women’s hostel with lowest fees was SRCC undergraduate hostel at ₹40,000. The most expensive men’s hostel was VKRV Rao postgraduate hostel at ₹81,960, whereas there are 4 women’s hostels whose fees exceeds one lakh rupees a year.

the men’s hostel with the lowest fees was at ₹24,295, whereas the women’s hostel with lowest fees was at ₹40,000.

The Pinjra Tod report also reveals that the men’s hostel charge a small amount initially as Annual Charges or Admission Charges. The rest of the fees is to be paid in monthly instalments. In stark contrast, women’s hostels require students to pay a hefty amount upfront right at the time of the admission as the annual charges are significantly higher. This is also the same month when students pay their college tuition fees and travel to the city with their entire luggage. The rest of the fees are again to be paid in fixed amounts by a fixed period of time, any delay leads to fine. Rules such as these act as deterrents against women and parents still remain hesitant about investing so much for their daughters.

So what is the rationale behind charging women more than men? Earlier, university spaces were dominated by men, which is the same time when most men’s hostels were built. The UGC had provided funds for their construction and these hostels still receive Annual Maintenance Grants. Most women’s hostels have been built in the last 10-20 years, when the number of women students in the university has drastically increased.

Women’s hostels have largely been built through the dubious ‘self-financing model’, where the financial burden of constructing and maintaining a hostel is put on the woman student. This should explain the ‘gender tax’ that women are expected to bear!

Graph representing the difference in monthly average fee of men’s and women’s hostels, as given in the Pinjra Tod Report’15

It is hence not surprising that even though women today constitute almost 50% of the student population in universities, the presence of women from marginalised communities still remains very low. Who can after all, afford such high hostel fees? Women’s hostels in colleges such as SGTB Khalsa College, Indraprastha College for Women, Daulat Ram College etc, have hostel fees that are above one lakh rupees a year!

The administration of various colleges would want women to be thankful for undertaking the measures to build hostels for them. However, in the name of being more ‘inclusive,’ they end up being exclusionary in practice by making their hostels available for only those who have the means to ‘afford’ it! Doesn’t that sit in absolute contradiction with the idea of public education?

education thus becomes exclusionary as hostels are available only for those who can afford it!

It has been a long struggle for women to enter institutions of higher education to where we stand today, where women are present in almost equal numbers as their male counterparts in our universities. However, the terms of women’s participation in the University is marked by discrimination. Women students are still accorded a secondary status, as is made evident in the wide discrepancy in the fees for women’s and men’s hostels.

Women students are made to feel grateful for even being present in the University and certainly, for first generation students, it is indeed a big achievement to mark their presence in unchartered territories that are marred by histories of their absence and erasure. But this is not to be used as an excuse by the administration to deny women their due by expecting them to remain contented with what they have, for it remained out of their reach for this long.

Providing hostel facilities to students is not something that should be seen as a ‘privilege’ that one needs to be grateful for. Rather, it should be seen as a basic responsibility of the University to provide the infrastructure to further enable women’s participation. The high fee is often attributed to provisions for greater safety (security, CCTV, surveillance). However, such rise in accommodation prices excludes many women from accessing proper accommodation and making the best of their educational opportunity and also is a question of access to education for women!

Therefore, a not-for-profit hostel built on public land and funded by donations cannot charge students more than several private PGs, that in fact work for profit. Women students are being made to pay for and carry on their own legacy of oppression since the move towards privatisation of education post-liberalisation. This of course being only in places where hostels for women exist in the first place! With most undergraduate colleges of South Campus still not having hostel facilities, the University has repeatedly ignored the implications of the lack of hostels in accessible to women, in a society where there has been a history of stigma attached with women attaining higher education.

Women students are being made to pay for and carry on their own legacy of oppression.

Another tool to further alienate women from the University has been the process of ‘re-admission.’ It was found by Pinjra Tod that postgraduate men’s hostels do not require any hosteller to vacate their hostel after every session. However, postgraduate women’s hostels mandate women hostellers to vacate their rooms after each session. It is only at the M.Phil level that women can stay on like their male counterparts. If women want to stay back in the hostel to pursue a summer internship, then there is simply no provision to do so.

I was also told by friends from the Law Faculty that in their time, women students who were hostel residents couldn’t take the evening classes for they had to adhere to curfew hours. Thus one can see that the hostel is no ‘comfortable’ place where women are treated as adults. The promise of providing a ‘safe haven’ is seen as a legitimate excuse to levying additional charges against them. Women are made to pay more for their own ‘safety,’ which only furthers their own securitization!

Plotting the fees of various men’s and women’s hostels. Courtesy- Pinjra Tod Report’15

All these mechanisms of control feed off and into each other – whether it be regulating women’s appearance and conduct, to deterring their capacity to access public resources and spaces, or curbing their mobility. They constitute the social edifice on which the imagination of a hostel space for women rests.

Women aspire to attain an education not only to be able to transform into subjects of capitalism and obey its demands of becoming “good employees.” They also carry within themselves their multiple identities, desires, sexuality, hopes, dreams. The University is not only a site of education but also a space for assertion of these multiple selves. By means of high fees and curfews, this is precisely what gets contained.

When wardens ‘complain’ to parents about the ‘misdemeanours’ of their daughters, they know well that the adverse effects of such a complaint may even result in the revoking of the woman’s admission. They not only disregard women’s adulthood, but also reproduce structures of paternalistic protection which is modelled on the patriarchal Indian households. Thus, University and family reinforce each other’s patriarchal order.

The University taps into the anxiety of the family which sends their daughters to study, by hiking fees. They know full well that they would readily pay up to ensure their ‘safety.’ The University then, uses the same family as a tool to curtail women’s movement, by citing the familial concerns as a reason for their protectionism.

Time and again, whenever there has been a rise in students movements, in order to weaken collectivisation of women from raising legitimate demands and to deter their political participation, the administration is seen to be setting a precedent by rewarding the ‘depoliticised/apolitical’ students by giving them space in the hostel while denying ‘dissidents/deviants’ the same.

Hostel authorities are very aware of the power that they have over students, which is why they hold the threat to deny hostel seats as a sword hanging over the heads of students to discipline them. The threat of losing the hostel seat, makes it completely impossible for women to register their protest and adds a non-negotiable clause of silence, even in the face of harassment.

The criminalisation of dissent and student organizations, and the systematic deprioritisation of higher education itself in terms of defunding for departments/centres, have generated a sense of unease in University spaces. The lack of hostels and its limited seats seem like a strategic step on the part of the University to maintain its upper hand on students by demanding their submission. When denied a hostel seat, students are pushed into the nexus of landlords and PGs who engage in an even broader range of discriminatory discourse that includes knowing of one’s religion, eating habits, caste, etc. while making the decision of taking in tenants.

Hostel authorities wield the threat of denying hostel seats as a sword hanging over students to discipline them.

It is time we realise that women have had to fight a lot of social stigma and prejudice to be able to study in Universities. The University should be financially aiding them and not making it even more difficult to manage expenses. Curfews already make it impossible for women to engage in any form of employment to independently support their studies.

To be sure, the resolve doesn’t lie in the inflation of the fees of men’s hostels so that they can be brought at par with women’s hostels. Rather there needs to be a demand for affordable and accessible accommodation for all students and especially students from marginalised groups. Education could be a tool for challenging the status that women are relegated to in society. But instead, the kind of education being promoted in the University and its attitude towards women students, furthers the same patriarchal, caste-based structures and conspires to keep women trapped within the same.

Featured Image Credit: Avantika Tewari

About the author(s)

Avantika Tewari is a researcher and social activist based in Delhi.