Nazariya is a queer feminist resource group working in the domain of gender and sexuality. Formed in 2014 by a group of queer feminist activists, the organization works towards affirming the rights of LBT people.

I had the pleasure of speaking to Ritambhara Mehta and Rituparna Borah from the Nazariya team.

The Nazariya Team

Aishwarya: What was the motivation behind Nazariya?

Nazariya: We realized that there are hardly any organizations in India that work on issues of lesbian, bisexual and trans people, especially those assigned female at birth. Secondly, we wanted to bring intersectionality between the queer, women’s and progressive left movements. It was important that we start an organization which would be a queer feminist resource group, and build linkages between violence, livelihood and queer issues.

A: You work specifically with people assigned female at birth (LBTFAB). What is the reason for that? What are their issues and how do you try to resolve them?

N: The queer movement is, not blaming the people who are part of it, exclusively male assigned at birth. There is a growing need for the representation of people assigned female at birth. So we made a conscious decision, without discounting the fact that there are different kind of issues that male assigned at birth people face. For example, we do recognize the violence trans women face, but there is more visibility for those issues.

But we don’t want to reduce Nazariya‘s identity to just a LBTFAB group. Our projects focus on LBTFAB people, without losing sight of the larger need to talk about issues of gender and sexuality, not just from an LBTFAB point of view. We also realize that there are other identities that may be marginalized, and they could be heterosexual people as well.

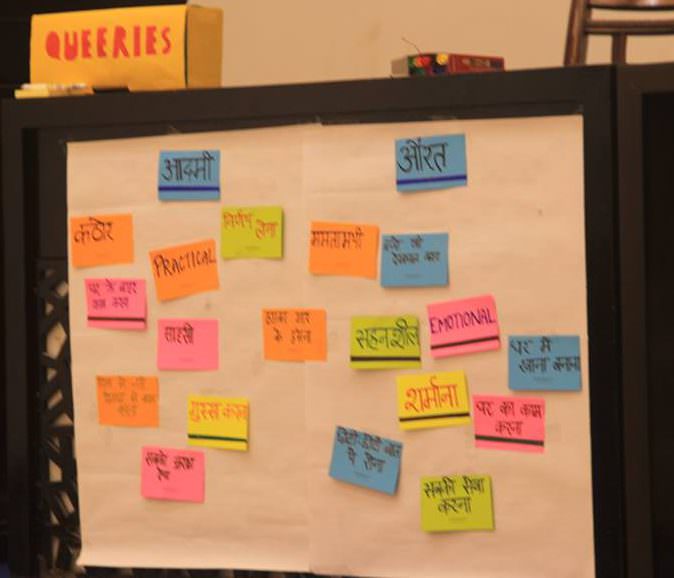

Discussing gender stereotypes at Nazariya’s workshop

The biggest LBT issue is invisibility. The population that is out and wants to come out is tiny. And LBT people suffer invisibility in the queer movement, women’s movement and general discourse. Even if people try to address LGBTQIA+ issues in the women’s movement, the discourse is often heteronormative. For example if the discussion is on violence, it is focused on marital violence – violence from husband or mother-in-law.

Other issues are forced marriages, IDs for trans people, coming out, public washrooms, lack of job opportunities, and harassment within the workplace. These are the issues we focus on.

A: What was the idea behind starting a helpline for LBT people? What has the response to the helpline been like?

N: We have an office phone that doubles as a helpline. Many of the calls are by the LBT people. Often we get calls from brothers or husbands of LBT people, trying to understand them. Then there are calls from people describing their sexual experiences and encounters, or how they realized their sexuality.

When we started Nazariya, we realized there is a need for such a helpline in Delhi. The frequency of calls has now considerably reduced, and our helpline is not that active now. But we get a lot of messages on Facebook. People also come and meet us in the office to tell us their issues and experiences. Maybe when we have more staff, we can run a full time helpline. But there is definitely merit in having a supposed space offline or online, which caters to this need.

A: Nazariya began working with the working class LBT people in Delhi in 2015. What has been your major learning from that project?

N: We’ve realized that there is lack of support space for the working class LBT people. People believe that queer community is mostly upper class. But there are many queer people in the working class. But queer theory is generally upper class. To be more inclusive, we switched from English to Hindi. But even that translation becomes upper class, because it does not match their spoken tongue. It can get tricky to discuss topics like pregnancy, open relationships, sex toys, Tinder, which are so common is queer discourse. We can’t use terminology like transgender, lesbians and gender neutral. It might be politically incorrect, but we have to say ‘ladkiya jo ladkiyo se pyaar karti hai’ (girls who love girls), and ‘ladkiya jo ladko jaisi rehti hai’ (girls who behave like boys). Another interesting point is that often earning members of the family find more acceptance within the family and community.

A: Can you tell us more about your talk series “Our Lives Our Tales”?

N: In 2015, we received some old books about the queer movement’s history in India. And we realized that the current queer movement does not know its own history. We only know about the movement from 2009 onwards, when Delhi High Court struck down section 377. So there’s an assumption that the movement was ineffective before 2009. But the movement was going strong, and was a lot more intersectional. It had affiliations with the progressive left movement. AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan, the organization to file the first PIL against section 377 was not a queer group. It was a group of people who had come together, including people from the Narmada Bachao Andolan.

A still from “Our Lives Our Tales” series

So we decided to organize these talks, and work on projects that talk about these queer histories in informal ways. Queer history is not as well documented because people want anonymity. We also realized that oral histories often get lost in the discourse of written documentation. So we will obviously come out with a report, but we will also document the histories in videos and put them up on YouTube.

A: You were closely involved in the case of Shivy, a trans person who was illegally confined by his family. Can you tell us more about it? What does the case’s outcome mean for other trans people in the country?

N: That was our first case. We had brought Shivy (who goes by Naveen now) to Delhi, and we didn’t have a clear plan. We tried to get in touch with the American Embassy but nothing worked out. When we realized that his parents had filed a kidnapping case, we got in touch with two lawyers, who took the case on a pro bono basis, and approached the High Court for emancipation.

It was a very progressive judgement. At that time Shivy did not have a trans or male ID. But the judge realized the absurdity of the situation. Shivy, who had been studying abroad, was brought back to Agra to visit his family and then forced to live at home. He tried to leave but his passport had been confiscated. But the judge was very clear. He told the parents to return the passport, buy a flight ticket, and not contact Naveen until he contacted them.

We don’t know how widely that case is used now, but it is a judgement that should be used a lot, since it talks about parental violence and rights of a trans person to self determine their gender.

A: You recently created a set of guidelines on how to report LGBTQIA issues. What inspired you to do so?

N: There was an article titled “Heartbroken ‘Juliet’…” and no efforts were made to anonymize the faces or names of the people involved. We got in touch with the journalist and he gave us their address without any verification. Ten years back reporting was terrible but now in 2017 we have news organizations regularly reporting LGBTQIA+ issues.

So we decided to organize a workshop, and take it forward to media schools and talk about those guidelines. We also realized that there’s no absolute right or wrong way in reporting, but such issues should be reported with some sensitivity.

Still from workshop on LGBTQIA reporting

One of the points we emphasized was how accurately one needs to talk about these identities. For example, if there is a report where a person’s gender or sexual orientation is not clear, a journalist can ask them what they identify as. A journalist should also have access to some resources, if the people they are covering need some kind of support. It shouldn’t end with just publishing an article. Also the idea was to be a little more conscious of women issues, or general gender sexuality issues.

Also read: A Handy Guide On How To Report On LGBTQIA+ Issues

A: In your experience, what is the biggest challenge the LBT community faces?

N: One thing that really comes to our mind is the invisibility of lesbian and bisexual issues within the LBT framework. There’s a lot of conversation around trans issues, and a law that caters to them. What scares us is that if Section 377 is not overturned, will we never talk about lesbian and bisexual issues? Or do we always camouflage their issues within the umbrella of women’s issues? It’s not harmful, but it’s something to think about.

A: What are Nazariya’s plans for the future?

N: We want to continue what we’re doing – training and research. We’re building a resource and support group where people can come and be themselves. We also want to talk about mental health, because it affects a lot of LBT people. Nazariya was started to make LBT lives visible, and talk about sexuality. That’s our long term goal, and we want to do whatever brings us closer to that.

All images courtesy Nazariya. Check out their work on their website here and follow them on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.