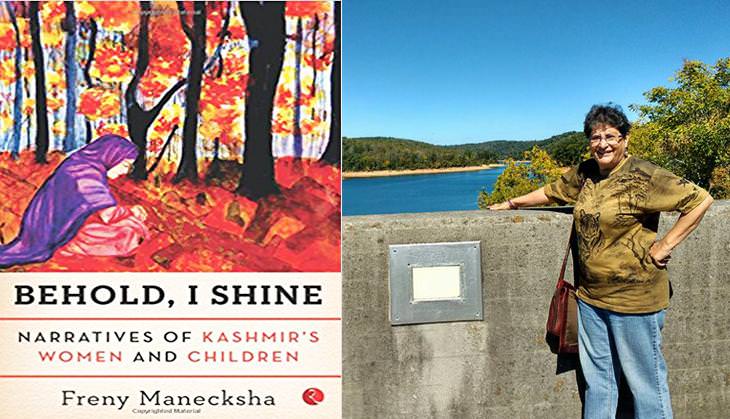

“Beautiful” and “conflict zone” – are two descriptions that are synonymous to Kashmir. Through Behold I Shine: Narratives of Kashmir’s Women and Children, author Freny Manecksha compels the audience to look beyond the prism of the “beautiful”, while herself holding on to the thread of conflict to bring out the female voices from within Kashmir. The book explores the ways in which conflict has affected Kashmiri women and children.

Journalist Freny Manecksha has been visiting Kashmir for years now and the book was a result of all her visits and interactions with the locals, especially women. Her book documents stories of women from the narrow lanes of Srinagar to the hillsides of Kashmir. The book allows women to be the speakers and can be perceived as authentic first hand accounts.

I read the book at the end of the day when I had worked myself out with the idea of what could happen if the curfews returned and what things would I have to hide. I was struck reading about the incident of a woman whose letters were made public during a crackdown and a village elder was made to read.

The book explores the ways in which conflict has affected Kashmiri women and children.

The book presents emotions intricately while maintaining a journalistic distance. In giving space to a Gujjar woman who was raped, the book manages to picture the complexity of reporting an act of sexual violence at the hands of state forces.

She (Pakeeza) could only confirm that it was the maize harvesting season. This is indicative of how difficult it is to document incidents of violence within communities that record events not according to a western calendar but by keeping track of nature’s cycles.

“Pakeeza told us that she had been making tea for two of her husband’s relatives- believed to be militants- when they saw troops approaching and ran away. The security personnel, dragged Pakeeza to another room in full view of some members of her husband’s family and allegedly sexually assaulted her. Pakeeza said she had no recollection of what ensued. In her words she ‘lost consciousness’.

Soon after, a security cordon was enforced around the area, making it difficult for her to venture out and record the crime. She recounted that a few days later, a senior army officer had offered the family a sum of 5,00,000 in exchange for silence; they were also assured that perpetrators would be suspended.

This dangling of money was a cynical exercise in manipulation whereby a poor family’s sense of honour was commodified. It created a marital discord.”

In a relatively conservative society of Kashmir, talk of anything remotely related to sex is tabooed. Having anyone to talk about sexual violence can be very difficult here and it often requires a lot of trust building. It is in this situation that Pakeeza and many women like her are expected to recount their experiences of sexual violence. In turn, she believed that the mistake was hers for the militants were from their community.

“How does she grapple with, not only the act[rape], but also the violence of the society that shames her, the victim?”

“How does she remain true to herself and her story when the sections of the society have already stigmatised her – viewing her as ‘ruined’, or having brought the crime upon herself?”

“How does she elucidate the sexual details when she comes from a society where such talk is considered inappropriate?”

The author finds a way of dealing with this by deciphering their expressions and body language. One cannot help but appreciate the way the author tries to bring into picture the community that has long been seen with suspicion by Kashmiris. The community of Gujjars is believed to be closer to the Army and CRPF and their allegiance is always questioned.

Also Read: What Is Everyday Life In The Kashmir Valley Like?

Any account of violence against women in Kashmir is incomplete without the mention of the battles of Association of Parents of Disappeared (APDP) and half widows. These are the women who were compelled to step out of their homes, often against their will. They are fighting a battle that will hardly have any closure. The bitter truth remains that the state can never do enough to give them justice.

Last summer, I heard Parveena Ahanger, Founder and Chairperson at APDP, speak at a public event speak about her struggle to find her disappeared son. She concluded by saying “Had it not been for finding his whereabouts, I would probably not even have stepped out of my house like this. I was compelled to be who I am today because of the state atrocities.” Since then, whenever I looked at the women of APDP, I wondered if she and others like her could have had totally different lives and priorities had there been no enforced disappearances of their close ones. The book throws light on lives of these women and compels one to think more about their struggles in locating their loved ones, not sure if they are alive and struggling to negotiate with society.

The book also traces stories of children during their formative years and their brush with conflict. They have memories of burnt homes and crackdowns where the army would ransack their homes and trample their toys. For Nayeem, the memories are embedded on his hand in the form of a missing thumb. What he calls a “memento from a school picnic”. He was injured from an explosive which was lying around; he picked it up, excited at having discovered something unusual.

The bitter truth remains that the state can never do enough to give them justice.

Woven around the thread of conflict, the book however fails to dissect it from different angles. The literature including the media reportage today ignores the fact the conflict is not a one sided aspect. It involves multiple players and the civilians are mostly caught in between. The book makes mentions the violence suffered at the hand of the army, the police and the CRPF, all of whom she refers to as “security forces”, but fails to mention atrocities committed by those that claim to be fighting for the cause of azaadi.

The book nowhere questions the premise of armed struggle and thereby proceeds with a sort of acceptance to it. On one occasion it does include a woman who was abducted and raped by militants. Unfortunately, the section about violence by-non state actors ends quickly. The author ignores the reality that during the early 90’s many took up arms to fight the state but ended up using it for their personal gains of settling scores with people they had personal conflicts with. The shadow of the gun was also used to create matrimonial alliances which I see nothing less than rapes.

Just as reporting a case of violence by “security forces” is because of the impunity they can afford, the violence by non state actors too remains gruelling because of invisible impunity they enjoy. Conflict further embroils the situation as the victim is always looked at with a degree of mistrust. Decades after their exodus, the Kashmiri Pandit community continue to be looked at with suspicion – was it a state conspiracy or were they really threatened and forced out of their homes by militants?

It could have been either. The truth remains that the civilian population suffers in multiple ways including sexual violence against women. This violence remains largely undocumented and doesn’t find a platform in books like this which intends to tell the stories of women in conflict. The book gives a passing reference to the story of Kashmiri Pundits in a footnote, and a mention of the abduction and killing of a Kashmiri Pundit woman Sarla Bhat. The inclusion of more incidents pertaining to the community would have provided a holistic picture of violence against women.

In the chapter “Josh tha, Jawan thay”, the author records Zamruda Habib describe that they (kashmiri women demanding azadi) would welcome militants and show their support by washing their clothes and providing logistical support. Others maintain that not all would welcome the militants and instead had no choice but to let in the men with guns in their hands. Zamruda who believed in empowering women to decision-making positions during college days, first became publicly vocal about gender rights after an incident of dowry harassment. However, she later aligned with Hurriyat and accepted that for the fight of azadi, gender issues had to take a backseat. As a reader, this premise makes me uncomfortable, as gender based issues are made subservient to the struggle for azadi and the author does not make an effort to give credence to dissenting voices.

The book therefore navigates the violence against women from a singular perspective that is political in nature and a limited understanding of gendered violence. Let’s subtract conflict from Kashmir for the sake of an assumption, would Kashmiri women have been in a better place in the society? And until azadi happens, is domestic violence and harassment of women going to remain untold? The book does not answer these questions.

“Has militarization eroded the cultural matrix (of Kashmir)?” the author asks. During 90’s and later, in addition to militarisation, the militants attempted squeezing the socialising spaces for women as well, by shutting down the salons and cinemas. The Dukhtaran-e-Millat tried enforcing Hijab by attacking women with uncovered heads with ink. While the latter finds a mention in the book, the former is missed out.

In the similar context, the chapter “Where else can I go?” the book interweaves the Sufi tradition of Kashmir and women finding a socialisation space in shrines. Following young designer, Mahum Shabir, the author documents the inside of shrines and observes women spending time there without the fear of aggression. The shrines give Mahum a space “to just be”, a conjecture that the author seems to generalise. The shrines, no matter how liberal, still fail in proving a flexible and non restrictive space to women. The entry in itself means acceptance of a certain dress code and there is no scope of inter gender interactions. A hearty laughter in that closed space is enough to attract attention judgemental looks. That is not typically a characteristic of a place where women can expect to be who they are.

Towards the end of the book is a chapter that talks about hijab and how women are becoming more assertive in their choices regarding hijab. The book builds the narrative around stories shared by six women, five of who wear hijab of their own will and one does not. The author believes the group’s choice to be representative of women asserting control over their dressing which is a gross generalisation. In most parts of Srinagar and largely in rural areas of Kashmir, dressing and morality are still closely linked and women do not have complete agency when it comes to their attire. Choice of dressing is not limited to parents accepting their daughter’s way of dressing, it is also about the society shaming women on the basis of their clothing. I have been at the receiving end of this and so have other women been.

Also Read: What Is Killing Kashmiri Women And Why Aren’t We Talking About It?

Earlier this summer I was inside a shrine compound when I was pulled aside by a middle aged man. He started hurling abuses at me and my parents for the hem of my salwar was resting a little over my ankle. Crowds gathered as I confronted the man. He remained adamant . He kept asking me about my religion and when I was left with no option that could bail me out of this situation, I had to yell at him and say “I am not a Muslim”. Once I said that, he let me go.

On one such day, I met 14 year old Bisma* from downtown Srinagar who feels that her hijab is taking away capability of feeling anything. Her family does not allow her to go out without it. One cannot understand how the author failed to interact with such women even in her frequent visits to Kashmir as a journalist.

The book concludes with a quote by Essar Batool, “….I can save myself,” which is the absolute opposite to Zamruda’s approach considering her compromise in accepting Hurriyat’s upper hand in decision making.

The book was released on August 16 at Srinagar in an event organised by Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS). In the discussion following the release, the role of memory in a conflict was discussed. The author, while quoting Foucault in her book, states,“since memory is a very important factor in struggle, if one controls people’s memory, one controls their dynamism. And one also controls their experience, their knowledge of previous struggle.”

Falling in line with the quote, the book does serve the purpose of preserving memories and transmitting these to future generations. Any further work on women in Kashmir will certainly have to take note of this one but all the same, the book controls memories by adopting a singular perspective. Although it remains the discretion of author to narrow down the inclusion of details, the reader feels a little betrayed in expecting to read a holistic account.

Featured Image Credits: Catch News

About the author(s)

A teacher and a learner.

Please note the quote…”I can save myself” is NOT made by Essar Batool and the book does not anywhere ascribe this quote to her.

Freny Manecksha