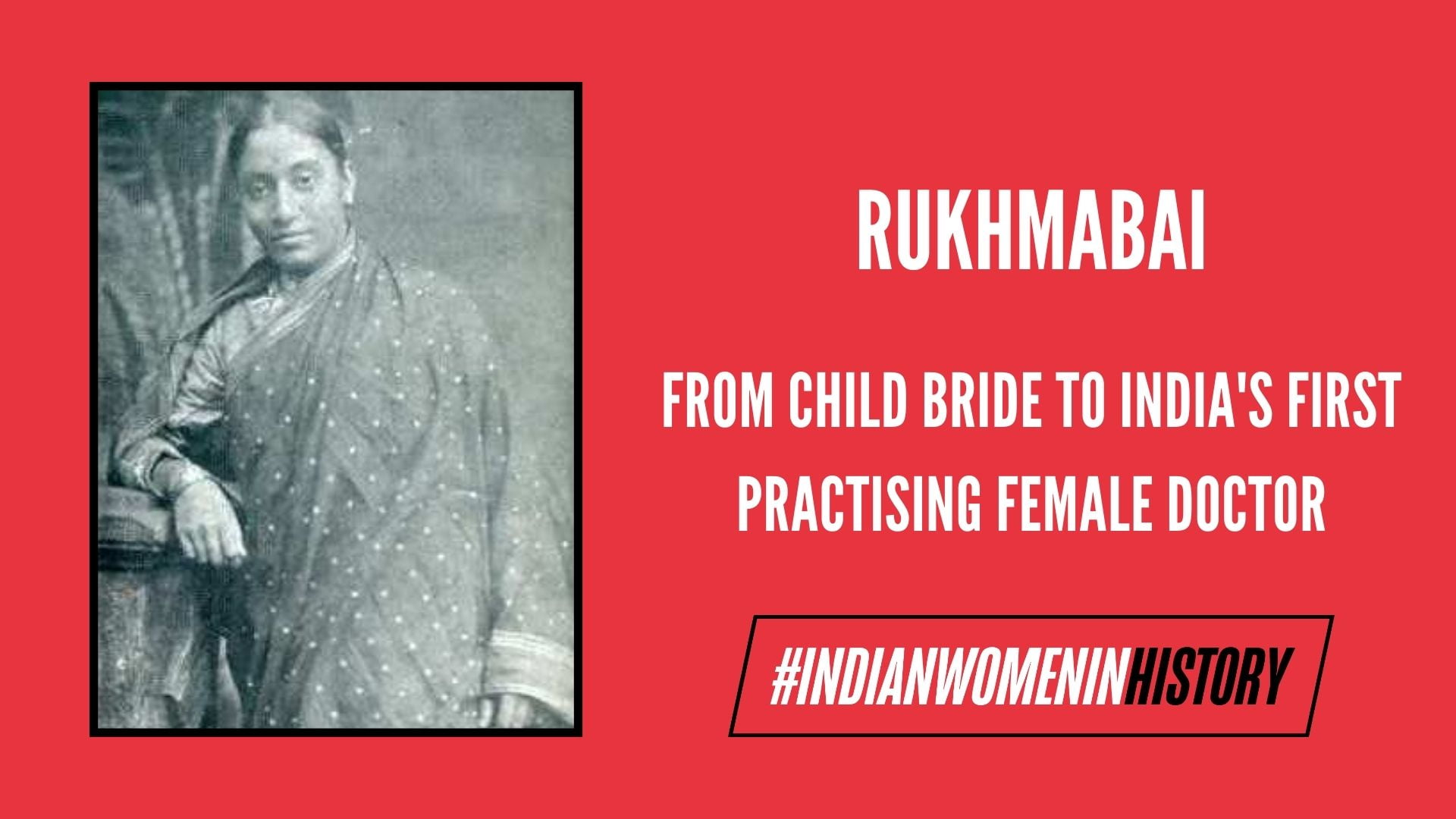

Rukhmabai (1864-1955) was the first practising female doctor in colonial India. Although Anandibai Joshi was the first Indian female doctor, she couldn’t practice due to her untimely death. Rukhmabai also made her mark in history due to the legal case she was involved in, which contributed to the enactment of the Age of Consent Act, 1891.

Early life

Rukhmabai was the daughter of Janardhan Pandurang and Jayantibai. Rukhmabai’s father passed away at an early age and her mother re-married Dr. Sakharam Arjun, who was a doctor and a professor. She was married off at the young age of eleven, while her husband, Dadaji Bhikaji was nineteen years old. Despite being married, Rukhmabai and Dadaji never lived together. Rukhmabai continued with her education.

Rukhmabai and Dadaji lived apart for several years, during which he did not worry about his ‘wife’. He later got in touch with her, perhaps interested in the money she had inherited after her mother passed away. She refused to go, continued to live with her step-father and pursued her education, going against the norms of society.

Dadaji sent a legal notice to Sakharam through his lawyers, in March 1884, asking him to stop preventing Rukhmabai from living with him. Even though the response to Dadaji was given in a civil letter by Sakharam, he eventually had to obtain legal aid for his daughter.

Despite being married, Rukhmabai and Dadaji never lived together. Rukhmabai continued with her education.

The case

In 1885, after 12 years of marriage, Bhikaji sought “restitution of conjugal rights”, where the hearing and judgement was presided by Justice Robert Hill Pinhey. Rukhmabai had refused to live with the man she was married to as a child, as she had no say in the marriage. The British precedents could not be implied in this case, as British law was meant to be applied in the case of consenting adults. Justice Pinhey found this limitation in British law and found no previous cases of such nature in Hindu law. Hence his judgement on the case stated that Rukhmabai had been wed as an innocent child, had no say in the matter and now couldn’t be forced.

The case came up for retrial in the year 1886. There was a lot of backlash from society, with some Hindus stating that the law did not respect the Hindu rituals and customs, whereas some praised the step. The judgement received a lot of criticism in the newspapers. While the case was being contested, one particular writer received a lot of attention for a series of articles, by the pen-name ‘A Hindu Lady’. It was later found that the anonymous author was none other than Rukhmabai. She wrote from a feminist perspective, on themes like child marriage, enforcement of widowhood and the status women had in society.

Also Read: Life Of Pandita Ramabai: Championing Women’s Education And Social Reform | #IndianWomenInHistory

In March 1887, Rukhmabai was ordered to go live with her husband or spend six months in jail. Determined about her decision to not to return to Dadaji and to continue her education, Rukhmabai bravely said that she would rather face maximum penalty than accept the verdict given.

Subsequently, after numerous hearings, the marriage was affirmed, where Rukhmabai wrote to Queen Victoria. The Queen overruled the court’s verdict and dissolved the marriage. In July of 1888, Dadaji accepted monetary compensation of two thousand rupees to dissolve the marriage.

It was a case that got a lot of attention in Britain too, where women’s magazines covered it. The ripples that the case created led to the influence on the passage of the Age of Consent Act, 1891, which made child marriages illegal across the British Empire.

Life in medicine

After the case closed, she set sail to go and study in England, 1889 at the London School of Medicine For Women. Dr. Edith Pechey supported Rukhmabai and helped to raise funds for her education. She got support from Eva McLaren, Walter McLaren and the Countess of Dufferin’s Fund for Supplying Medical Aid to Women of India.

She returned to India in 1894. She joined a hospital in Surat, declining an offer from Women’s Medical Service to join a state hospital in Rajkot run for women. For thirty five years she served as the chief medical officer, then retired in 1929/1930. She passed away in 1955 at the age of 91.

Also Read: Historic Indian Women In STEM We Don’t Know Of But Should

Legacy

Rukhmabai’s story has been incorporated into books like Dr. Rakhmabai: An Odyssey, by Mohinī Varde. In 2016, a movie about her life was made: Doctor Rakhmabai, directed by Ananth Narayan Mahadevan and starring Tannishtha Chatterjee as Rukhmabai.

Rukhmabai, was a strong and determined woman, who did not give in to society’s constraints. She completed her education, and also fought for her liberty and consent by standing against the institution of child marriage. Despite fighting the legal case for year, she kept serving as a doctor to help her patients.

About the author(s)

Shivani is a day dreamer, a foodie, a dog lover and a chai enthusiast. She is a resolute feminist, and loves to learn more and more about gender issues.

thank you so much for this post, check out my feminism articles on sociologygroup.com

it is strange to see a native indian with her Bindi is missing, is this a missionary aim and make indian bindiless.