I always knew, even when I was younger, that some events were supposed to be kept secret. And I did.

In due course of time, these events contracted into subjective narratives, into stories of personal shame. By their nature, these stories were overpowering, revealing flaws in my character, and completely defining me thereafter. As one story of personal shame found another, the depth of this vault in my consciousness increased so much so that there was very little space for light to enter. As is the characteristic of dark spaces, the vault became scary, as did the stories.

I witnessed their growing strength and their power over me. In the absence of any external support and inner wisdom, I decided not to look at them altogether, wishing they would go away. It was the only way I could function was to walk along with contemporaries in the pursuit of life. But the stories of personal shame weighed upon me and I brought this weight often without any choice, into various aspects of my life.

Then I was exposed to the tell-all, sensational talk show culture of the West — a culture that wanted every detail that it could get out of a story. As overwhelming as this culture was, it had one quality that made it outstanding. It always had an audience. There was always someone willing to listen, someone who was interested, and someone who always responded to the story—be it in agreement, in shock, in disdain, or in apathy.

It was not that I wanted to tell my stories of shame nor was I ready to tell them. But the audience’s presence made me feel less insignificant, less lonely. Consequently, I found myself revealing my stories, unfortunately to insensitive and intolerant people. Naturally, I felt disregarded; sometimes I felt misunderstood by them, but mostly I felt I was betrayed.

The audience’s presence made me feel less insignificant, less lonely.

I was denied the right to victimhood. Shocking as I found it, I was accused of having misunderstood the act of perpetration or having been an accomplice, an equal participant in the deed. It seemed they were asking me, “Why should you think of yourself as a victim?” At another level, there was a certain impatience, hinting at getting it together and moving on. That I should aim to achieve despite what happened, leaving untended that my chances to pursue success could have been compromised because of the trauma I had suffered.

There seems to be a rush in asking victims to get over victimisation; as if saying that victimhood is an unneeded state that the culture can no longer tolerate of its individuals. That victims are permitted only a certain finite time to live their victimization, which is in turn dependent on the nature and duration of the trauma inflicted upon them.

It also seems that victims are constantly being watched. Because a victim insinuates the presence of an external perpetrator and an ineffective system, a victim who takes a little longer to heal exposes the culpability of the culture. By default, such persons are penalised often by blaming them, disbelieving their stories, removing access to resources for healing and by forcing them to get over their victimization, faster.

there was a certain impatience, hinting at getting it together and moving on.

What is often ignored is the consequence of this impatience, of this hurriedness. One of the ways this rush affects victims is by forcing them to form alternate stories of the trauma, which are acceptable in the culture. In my case, the alternate story was, “I am unaffected by the sexual abuse.”

I was trying to take the story trimming off its excesses, its emotions, its subjectivity, and reducing it to nothing. In doing so, I inflicted further violence upon myself because I could not afford to lag behind and should not be perceived as weak, vulnerable and without agency. However I wonder, when I had to reframe my story, did I really have any agency?

In her riveting book Intimate Reading: The Contemporary Women’s Memoir, Janet Mason Ellerby makes a case for reclaiming the term victim and the “value in listening carefully to all women’s stories, but especially to women who have had to be silent.” Rahila Gupta asks us to consider, “whilst ‘survivor’ is important because it recognises the agency of women, it focuses on the individual capacity, but the notion of ‘victim’ reminds us of the stranglehold of the system.”

The process of healing is long and certainly not linear.

Victims of trauma move according to a pace comfortable or known to them on what Jennifer Dunn calls an agency continuum. When we tell our stories of trauma, violence, and pain, we are not doing so because we crave a label. We tell our stories because we want an acknowledgment that wrong was done unto us. Ellerby quotes Judith Herman, “This work of reconstruction actually transforms the traumatic memory, so that it can be integrated into the survivor’s life story.”

I am still healing. I am a victim and I am a survivor. Both stories are true.

Also Read: Victim Blaming: A Trope As Old As The Hills

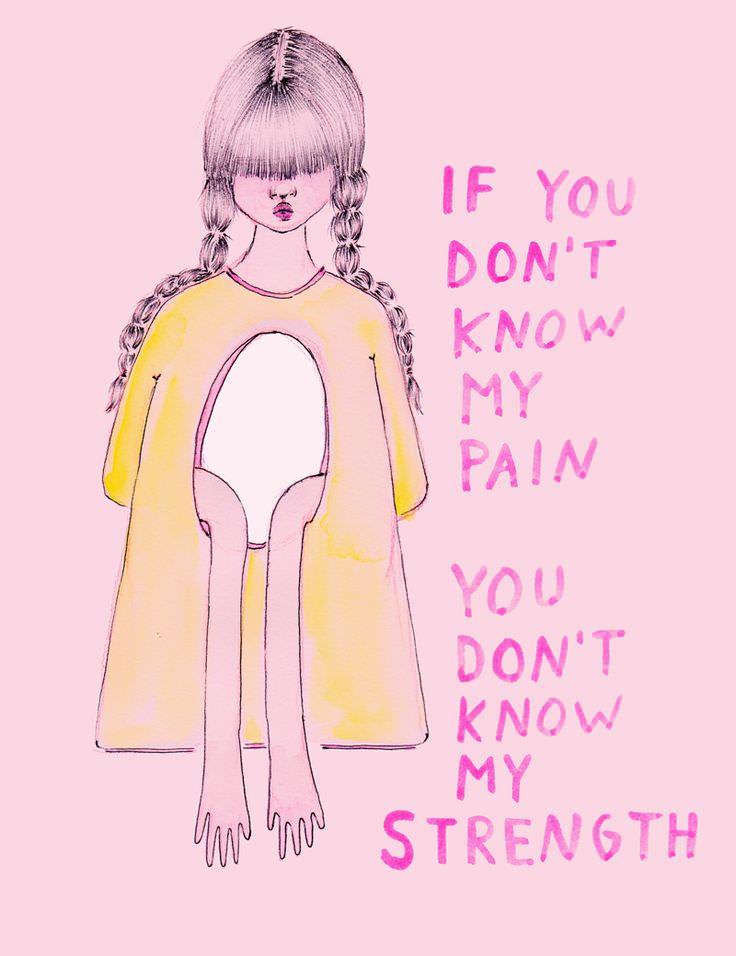

Featured Image Credit: Pinterest

About the author(s)

Rathi R teaches sociology and psychology at a media institute. When she is not teaching, she reads postcolonial and feminist literature and nonfiction writings. She has Master's degree in Social Work and is currently based in New Delhi. She writes at ratzest.wordpress.com.

I too feel uncomfortable with the victim-survivor binary. It is too neat and too watertight. I am sorry to hear about your experience. I can totally relate to it – being asked to move out of the victim position to the survivor position as soon as possible. I’ve begun to believe it’s a result of people’s discomfort with pain.