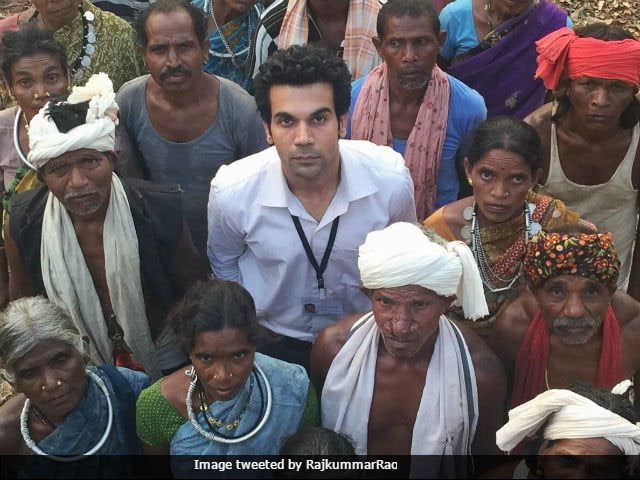

Amit Masurkar’s Newton follows the story of a first-time (presiding) election officer’s attempt to conduct fair elections in the Naxalite-ridden jungle of Chhattisgarh. The film stars Rajkummar Rao, Sanjay Mishra, Raghubir Yadav, Anjali Patil, and Pankaj Tripathi. Newton, played by Rajkummar Rao is a sincere, bookish idealist who believes in upholding order, discipline, and procedure. He wants to make a difference and is tired of the visible display of corruption and disarray around him.

Perhaps these beliefs are rooted in an overarching search for legitimacy, a conviction that the state machinery can act in a just manner if the rules are followed. The film places him in the midst of a militarized, conflict-ridden forest where the notion of legitimacy, ideals, and ethics sound farcical. There is a play between the tension of what should be and what is, confounding the viewer with the harrowing question of whether the ‘should’ can be abandoned.

The film begins with the embarrassing campaigning of a politician who towers above the people as he stands on a vehicle and delivers a sermonizing appeal for votes. A few minutes later, as he drives into the forest, a group of Naxalites take him out of his car and shoot him. The television screen in Newton’s house rings with the news of another act of violence inflicted by the Maoists who have declared a boycott on the upcoming elections. The film thus situates Newton as distant and outside of the violent reality of conflict, but as an active consumer of the information that is disseminated about it through the mainstream media.

In a dusty basement, Sanjay Mishra conducts a briefing for election officers. He says “We ensure that elections here take place with utmost honesty and responsibility even if those elected and sent into the parliament are criminals and hooligans.” This statement should prick the viewer, elicit a sense of dismay and outrage at the state of things. Unsurprisingly, the packed movie theatre finds itself erupting into a series of chuckles.

Dark comedy urges one to laugh at morbidity, what should perturb us seems to have a wry lightness about it. It offers an interrogation of appearances, a fracturing of what is accepted as the ‘normal’. And in this rupture, the disembodied space between the expectation of the norm and what really is, the only recourse that one is left with is dry laughter. Perhaps, this dry subtlety allows for a more critical engagement with the image where the viewer finds herself asking various questions about the nature of the reality that is being articulated on the projector. Newton pushes the viewer into this disembodied space where questions regarding social change, idealism, and what it means to be human are posed.

The film highlights how the military throttles the voice of Adivasis through violent acts.

Newton is presented as deviant from the norm, his obstinate opposition to disorder and lawlessness gives character to his resistance. His rebellion is in wanting to uphold a system that has long fallen apart for those around him. The subtext in the film points to how Newton could perhaps be Dalit, after he rejects a marriage proposal for the bride is under-aged; his angered father tells him that he isn’t going to get an upper-caste bride. There is a painting of Babasaheb Ambedkar lying on a corner in his house. Newton is an office clerk who has been placed in the ‘reserve’ section of election commission officers.

Masurkar’s Dalit protagonist is unburdened by the weight of his identity and history. There is a contradiction in the manner in which the film seeks to confront the margins. His caste identity is effectively erased, a minor detail about the character that does not demand any discussion in the shaping of the film. Such a representation of social identity can be problematic as it falls in line with the notion that one’s caste is a meaningless category, an idea that upholds the effacement of those who belong to marginalized social locations.

Every character in the film has a story to offer. Assistant Commandant Atma Singh is well-acquainted with spaces of conflict, having been positioned in heavily militarized areas such as Kashmir, Manipur, and Nagaland previously. He ‘knows’ how things are to be done, the question of fairness, order, and procedure are irrelevant for him in the doing of things. And yet, Masurkar is careful not to demonize this figure. Towards the end of the film, we see Atma Singh at a supermarket with his family, his wife asks him if they should purchase olive oil next month for the bill is too high, this looks like a simple family trying to get by. A simple family entrenched in a violent structure where Atma Singh has been rendered a cog that mechanically acts to perpetuate this viciousness.

Malko, the local election officer is looked at with great suspicion by Atma Singh, just as all Adivasis are, even the nine year old kids who are simply playing around the trees. There is a scene where all the election officers are visibly tired and irritated as nobody is showing up to vote, Newton turns to Malko and asks her, “Kya tum bhi nirashawadi ho” (Are you disappointed?) Malko responds: “Nirashawadi nahin, main Adivasi hoon” (No, I am an Adivasi). Malko is also a school teacher who must struggle with the linguistic differences of the state board’s formal education system.

Malko’s parting words to Newton urge him to develop his sixth sense, an intuition that can take precedence over his idealism, and further guide it. Her words shape the climax of the film and bestow Newton with a stronger moral compass.

Also Read: Kabali Review: A Film In The Direction Of Non-Brahminical Ways Of Life

The election is conducted in a school located in a settlement where the houses have been burnt down. On the school building, text written in red expresses angry sentiments towards the military that has displaced the Adivasis. Newton is baffled at the sight, he repeatedly asks why the houses were burnt but is met with no answer. As he looks at the wall, Malko tells him “They burnt the houses; people are bound to feel angry”. The space where most of the film takes place is thus haunted by this horrific phantasm of displacement.

The military goes to round up the villagers to get them to vote on the instructions of a senior officer who is bringing a foreign journalist along. Adivasis are caught up in an expression of fear and confusion, some even choose to run away and are chased after. The soldiers don’t speak the same language and look at them with an eye of suspicion. The sequence produces a moment of debilitating helplessness, the impatient soldiers engage in acts of humiliation and the images are juxtaposed with a woman slaughtering and cooking chicken. Later, the military will feast on this for lunch.

Newton attempts to explain the voting process to the Adivasis. He tells them that their votes will go to Delhi where they will be used to elect a representative leader. An old, weak looking man stands up to inform him that he is their leader and they can send him to Delhi. The theatre laughs.

Malko informs Newton that they are not acquainted with a single politician on the list. At this point, he attempts to explain how the democratic process, governance, and law operates (in the words of Atma Singh, delivers a civics lesson). Malko interjects: “But sir, we have our own rules”. Newton, visibily irritated, tells her to let him speak. He asks the Adivasis what they want. One of them wryly comments, “If we vote, the Naxals get angry, if we don’t vote, the army does”.

Newton embodies all the masculine goodness of the state as put on paper, coming from a position of prescriptive rationality. Yet, Malko, the Adivasi woman who belongs to this space and reality attempts to direct his attention towards the indigenous customs and rules, the lived reality of the people that is erased from what the state prescribes on paper. The ‘democratic’ state’s attempt to assimilate Adivasis will fail if it refuses to let them speak and continually erases their voices.

the media blackout concerning the lived reality of Adivasis preserves a distance between the margin and the mainstream.

Atma Singh’s interjection comes from the cynical, lethargic position that such a conversation holds little value. What does it matter what Adivasis wants and how the ‘legitimate’ procedure that the state has prescribed should function? Atma Singh is the violent yet banal arm of power that must contain hierarchy and allow power to operate in a particular manner.

Soon, the media floods the election booth to capture this exotic, foreign region haunted by conflict. Newton stares at the spectacle being played out a few footsteps away from his desk. Cameras rolling, microphones being pointed at the the military and the Adivasis. Atma Singh awkwardly states that there should be greater investment in the military for they are in dire need of night vision goggles.

An Adivasi person is asked if the election will change things. He says nothing will change with a narrow smile and a voice that is neither angered nor frustrated, simply tired. The reporter asks him why he says so with an urgent, probing voice. He offers no explanation, smiles for the camera awkwardly as he wishes to leave.

How the ‘Indian citizen’ interacts with Adivasis that inhabit the margins of the mainstream imagination is largely conditioned by the media’s representation of the same. The film highlights how the military throttles the voice of Adivasis through violent acts while the media blackout concerning the lived reality of Adivasis preserves a distance between the margin and the mainstream. Newton gazes outside the election booth at the despicable state of things that are incompatible with his idealism, the unbridgeable gulf between what is and what should be.

The film is laced with quietude and distance. The conflict and violence is alluded to but never shown. One of the last sequences displays a bulldozer moving over barren land. For me, this was one of the most harrowing sequences for it was such a stark contrast to the luscious, green jungle. One reads about the land grabbing that has been taking place in the forests of Chhattisgarh to pursue ‘development’ and ‘progress’ and yet, little do we wonder who this ‘development’ and ‘progress’ is for. Little do we wonder about the growing presence of militarization, and whether this is the ‘right’ way to address conflict.

Newton makes the viewer wonder.

Also Read: Film Review: On Sairat and Custodians of Love

Featured Image Credit: NDTV

About the author(s)

I'm pursuing a major in Economics and a double minor in film studies and peace and conflict studies and I strongly believe in the importance of words, particularly the ones that are left out.