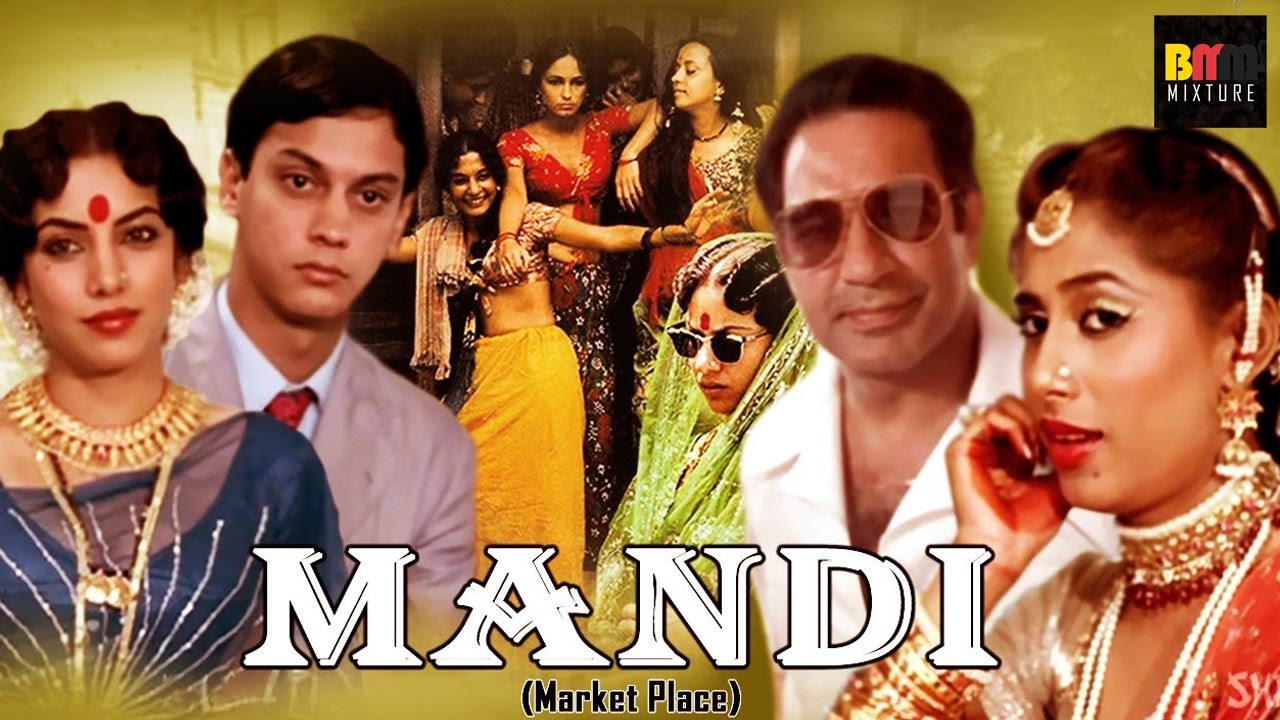

Mandi, directed by Shyam Benegal is a black comedy that is helmed by a heavy star cast, an intelligent script and a challenging theme. Released in 1983, the film changed the way Hindi cinema looks at sex work, the lives of sex workers and the paradoxes within society that lead to their marginalization.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6jRzreHglE

The film is centred on Rukmini Bai (played by Shabana Azmi), the Madame of a brothel that lies right within the heart of the city. It is surrounded by busy streets and continuous activity. But nothing compares to the riot of laughter, madness and continuous chaos that ensues inside the brothel almost every day. Rukmini Bai treats the girls in the brothel like her own children- she is stern, yet protective, loving but sneers and snaps at them for lazing around, much like any other mother-figure.

But what is unique in this film is that the relationship that Rukmini Bai shares with the other sex workers is not hierarchical or exploitative. The girls living there are her own, and she treats them like family. Thus, neither are any of the girls forced to work, or kept under continuous surveillance or ill-treated and abused.

For the girls, the brothel is their own home as much as it is a source of their income. They treat sex work like any other form of labour and thus do not see themselves to be oppressed or marginalized. And indeed, in their home, it is far from that. They are agentic human beings who decide when they want to work, if they want to work and who they accept as their client. Rukmini Bai is their mother, and they treat her as such. The girls are close friends with each other and spend a lot of their time gossiping about the happenings in the house and the neighbourhood.

In one particular scene, this emerges out strikingly when Rukmini Bai along with two other girls, Zeenat and Basanti (Played by Smita Patil and Nina Gupta respectively) return from a performance at an engagement party. They step out of their car, dressed to the T, laughing, having enjoyed themselves and enter the house – when Rukmini Bai orders them to go to sleep, but Basanti runs off to gossip about the evenings happenings with her other friends, where she gushes and giggles about the man who was enamored by Zeenat at the party.

The central plot point of the film is a battle between the girls and the politicians and businessmen who form the elite and ‘respectable’ part of the society.

What moved me, was the simplicity and obviousness of the scene. This scene exactly replicates the happenings at any hostel or sorority, where a flow of immediate gossiping, analysis and dissection of an event takes place, once somebody has attended it.

Among the girls, Rukmini Bai seems to nurse a soft spot for Zeenat, who sings spectacularly. She is kept away from sex work and focuses more on her musical abilities. Her room is on the first floor, away from the chaos, where she silently strums at her sitar and practices her music. The men who frequent the brothel are enamoured by her voice and beauty but have been strictly instructed by Rukmini Bai to stay away from her.

Her virginity, however, could be construed as a problematic element in the film. Not only does Rukmini Bai openly acknowledge her bias when it comes to Zeenat, she often breaks into exclamations’ of how the brothel is dependent on her talent and beauty. It can be however presumed that she will also cash in on her virginity at an opportune moment, given that she says that Zeenat will ‘only go with someone special’.

The central plot point of the film is a battle between the girls and the politicians and businessmen who form the elite and ‘respectable’ part of the society. They are the self-appointed guardians of morality and ‘culture’. Shyam Benegal is not subtle when it comes to satirizing these characters and pointing out their hypocrisy.

It is a break from earlier Bollywood films that have treated sex workers as either victims or villains.

The Nari Niketan (Women’s organization) of the city is engaged in an effort to end prostitution in order to protect the fragile morality that apparently gets disrupted by the presence of the thriving brothel in the middle of the city. The confrontations of their leader Shanti Devi and Rukmini Bai are hilarious as Rukmini Bai, almost effortlessly, thrashes to the ground all accusations against her and reminds Shanti Devi very politely of her own hypocritical ways, when she holds the girls to different moral standards due to the virtue of their profession.

However, this brings me to another interesting element in the film. Rukmini Bai always asserts that her girls are artists and should be treated like one. The refusal to be termed as a sex worker brings out the high stigmatization and marginalization associated with it, something that both the audience and the writers of the film are aware of. Some of the girls, however, especially Soni Razdan’s character makes no qualms about being a sex worker and owning the term as well as the implications that follow.

The film also does not romanticize the sisterhood within the brothel. At the end of the film, it is made clear that everyone is primarily concerned about their own well-being when the girls ask Rukmini Bai to leave the now-relocated brothel. This is strikingly realistic. It does not invalidate the bond that they have shared but only concludes that in a society that is unforgiving to sex work and trapped in their own paradoxes and hypocrisies, one has to think of oneself first.

The film is undoubtedly a masterpiece. It is a break from earlier Bollywood films that have treated sex workers as either victims or villains. Mandi acknowledges their agency, dignity and status as workers and holds them to the same moral standards as any other person in the film.

Also Read: Films, Flair, And Feminism: Celebrating Smita Patil | #IndianWomenInHistory

Featured Image Credit: Youtube

About the author(s)

Sunaina Bose is a theatre enthusiast, pop culture junkie and an Austenmanic. In her free time (also when she’s procrastinating) she loves to take life changing quizzes like ‘What kind of pizza are you’.