In recent times, a need to focus on feminist writings has emerged with the global discourse and political scenario shifting to social, political and economic equality. India has a wide array of feminist resources and material. However, these have been hard to find and have been collated over the years through the efforts of many women who believed in and championed the cause of feminism.

The findings of these texts have made two points evident – Indian feminism is different from feminism in other countries. Herstories, although hard to find, change the narrative of history to a great extent, adding gender inclusivity to the currently skewed narrative balance in historical records.

Sanjukta Ghosh, writing for Dissent Magazine on the book ‘Feminism in India’ spoke about the palpable differences in feminism as experienced by women from different countries and cultures and the need to not call them all the same, saying, “Different geographies and histories are conflated until difference is lost and one ‘third world feminism’ becomes interchangeable with another, collapsing into one theoretical model the multiple struggles of very different women under very different conditions”.

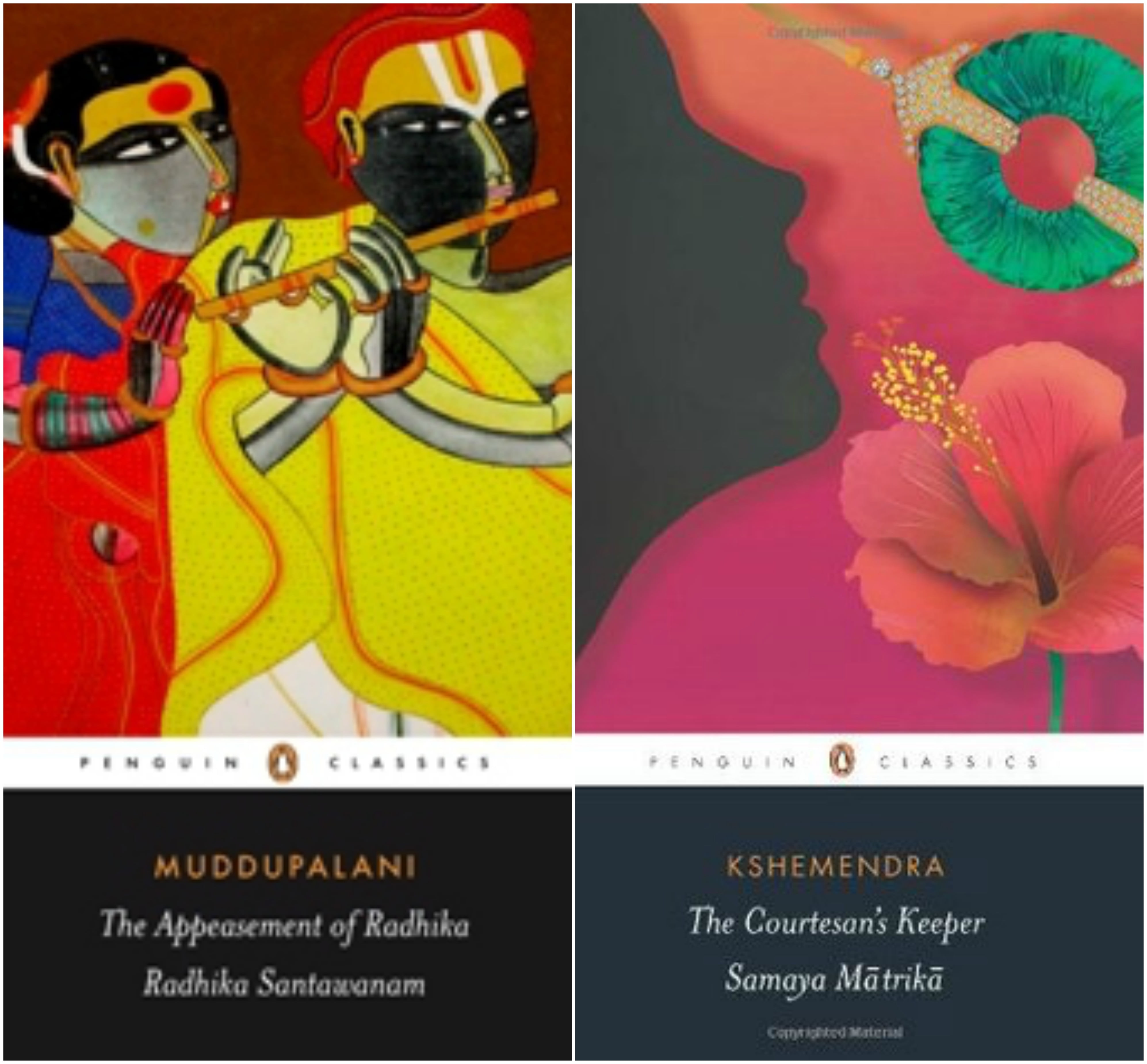

Kirthi Jayakumar, a feminist, activist and author has said, “History has traditionally been written by the male hand, so women are seldom mentioned. The oppression of women’s free speech continues today”. This theme was interesting to note in the differences between the two pre-colonial texts – The Courtesan’s Keeper (Samaya Mātrikā) by Kshemendra and the Appeasement of Radhika: Radhika Santawanam by Muddupalani – and the very different audiences they both received.

Kshemendra’s text doesn’t seem to have faced any opposition in history. Muddupalani’s Radhika Santawanam, while being praised during her time (the era of Raja Pratapsimha of Thanjavur), did receive considerable opposition when it was re-published in its full text by Nagarathnamma, following the printing of “sanitised” versions of the poem.

Nagarathnamma’s edition of Muddupalani’s book was published in 1910 by the Vavilla Press and was banned in 1911. It was finally restored to its rightful place in Indian literature in 1952 by the Chief Minister of Madras, Tanguturi Prakasam, who said this was “restoring a few pearls to the necklace of Telugu literature”.

The introduction of Radhika Santawanam (published by Penguin Random House India) tells us that the literary critic Kandukuri Veeresalingam condemned Muddupalani’s graphic descriptions of intercourse saying, “Several references in the book are disgraceful and inappropriate for women to hear, let alone be uttered from a woman’s mouth”.

He also called Nagarathnamma an adulteress and a prostitute. Nagarathnamma had responded immediately, saying, “Does the question of propriety and embarrassment apply only in the case of women, not men? Is he (Veeresalingam) implying that it is acceptable for Muddupalani to write about conjugal pleasures in minute detail and without reservation because she was a courtesan?” Nagarathnamma successfully combated all notions of womanly propriety that government and society sought to impose as hegemonic ideals on women, restoring what was unspoken and intrinsic.

With the silencing and invisibility of so many herstories in the tomes of history, it becomes urgent and important to go back and find these stories of women, hence changing the unilateral and limited view of history to a more inclusive and comprehensive lens. It is also interesting to look for elements of feminism in pre-colonial texts since contemporary feminist views differ to a great extent and the times in which these texts were written differ radically from our own.

It was interesting to read The Courtesan’s Keeper as it is a novel that centres around 2 women – Kalavati, a young courtesan, and Kankali, a retired courtesan with valuable experience – and was written by Kshemendra, a man. Set in the 11th century, it offers an insightful glance into the life of the people in the Kashmir valley, particularly the courtesans.

With the silencing of so many herstories in the tomes of history, it becomes urgent to go back and find these stories of women.

A feminist element that prevails in the text in the characters’ years of maturity, is choice. It can be gleaned at first glance and is interconnected with the rest of the elements. Sexuality as a choice is celebrated in the text and not shunned.

Elements of feminism included are also social mobility and freedom of movement. Women can inherit property and litigate in courts as witnessed especially through the life story of Kankali. She has held many positions – thief, courtesan, wife, witch, beggar, Buddhist nun, wet nurse, herdswoman, cake seller, astrologer, liquor hawker, ascetic – and properties albeit by conniving means. She has also travelled within India and beyond – including Guada and Vanga (Bengal) and Turushka (Turkey) – changing identities and professions.

This gives way to two other feminist elements which are mentorship and collaboration. Kankali acted as a mentor to Kalavati, helping her strengthen her position as a courtesan and maximise her business profits, leaning on her own personal experiences to do so. Her first practical lesson to Kalavati was how to extricate massive amounts of money from wealthy men and for this, she used the rich merchant’s son, the gullible Panka. There seemed to be no business where people at the heart of it didn’t use tricks – whether priests, merchants, doctors or courtesans.

Kankali was erudite and able to earn a living at every stage of her life, irrespective of her age. Through her, Kshemendra portrayed a woman who acquired wealth and knowledge throughout her life and was smart enough to do so, gaining multiple skills by being open to learning and collaboration. This shows an extremely entrepreneurial side and challenges the notion that with the fading of a woman’s youth comes her doom.

Her success was based on her ability to make the best of what she had, and these actions of Kankali are an echo of the sentiment of feminism as she tried, albeit inadvertently, to close the gaps of social, intellectual and economic standing with her privileged counterpart and taught Kalavati to do the same too. She says in the text, “Money is dearer than life. It comes from neither lineage nor conduct, neither learning nor beauty. To acquire it you need brains”.

Kshemendra also mercilessly depicted the folly and deceit of the males and the females of the era, and their quest for wealth, although it’s unfair to levy ‘deceitful’ as an adjective on the women of the text since their choice, in their early years of life, was bound to a great extent, and their need to be deceitful in their later years was a product of the same.

Also Read: 7 Times The Women In Mahabharata Got Their Due

Again, on the note of morality, Kshemendra puts forward choice, as seen in the text, “These fawns see deer traps in the forest every day, but even then, they let themselves get ensnared”. An interesting observation to note is that while Kshemendra uses the terms “whore” and “harlot” in the text, he never uses them in a derogatory fashion, which is to say that he portrays the characters with the respect and dignity that they deserve.

Radhika Santawanam by Muddupalani is a poem which is a sringara prabandham i.e. an erotic epic. A great feminist element of the text is sexuality and its description, especially because it describes the sexuality of women (Radha, Ila and the gopikas) in great and vivid detail. It also embodies sexuality across all ages and includes representation of them. Sex isn’t treated as taboo in the text, especially as even a god is associated with it – “Them and others more he (Krishna) fulfils / Much like the moon lighting up the world”.

The prologue or the avatarika is very interesting. In one part, it portrays intersectional feminism because Muddupalani takes glory in her lineage and caste which is significant as casteism was upheld in Ancient India. She takes pride in penning that her father was born into the Sudra caste – “From his holy feet was born / Into the Sudra caste, / A man called Ayyavaya”. It is certainly a feminist stance for Muddupalani to describe herself with confidence and weave herself into the prologue, taking complete pride and ownership in her work and accolades –

Which other woman of my kind

Has written the Ramakoti?

To which other woman of my kind

Have epics been dedicated?

…

Which other woman of my kind

Has been honoured by kings and lords?

Which other woman of my kind

Has won such acclaim in all the arts?

…

This is the daughter of Muthyalu

Incomparable, is Muddupalani.

We see the element of mentorship coming through when Radha teaches young Ila the ragas, the veena, mudras, rasa (the essence of the kavyas), writing, style, sophistry, elegance and passion. It is a passing of the torch of sorts and Radha willingly and freely passes this knowledge on to Ila. Muddupalani also portrays Radha’s yearning for Krishna in great detail, which highlighted a woman stating her needs, especially with regard to love and sex –

Afraid that it would come between our bodies,

He refrained from applying sandalwood paste.

To avoid any disturbances,

He did not raise the curtains.

Afraid they would obstruct an embrace,

He avoided wearing necklaces.

Afraid that my thighs would hurt,

He desisted from wearing anklets.

Close were we, he and I,

like ornaments mingling,

Like a flower and its perfume,

Like sesame and oil …

How, O little one!

How could he do this to me?”

-Chapter Three, Radhika Santawanam, 33, 1-17

Rosalyn D’mello, in her review of Radhika Santawanam for Open Magazine, says, “The reader is overwhelmed by the force of Radha’s sexuality”. She also quotes the introduction of Women Writing in India, Volume I by Susie Tharu and K. Lalita – “No other Telugu poet—man or woman—has written about a woman taking the initiative in a sexual relationship”. Muddupalani left no stone unturned when it came to the portrayal of female sexuality in her poem. A feminist attribute of Muddupalani’s work would also be that she wrote Radhika Santawanam itself, given that women’s sexuality is policed till date.

Muddupalani portrays women and their sexuality; Kshemendra shows them in power, in command of their sexuality and more.

A feminist element of the text is also the roles in which women have been portrayed. At Radha’s abode, while there is a woman holding “a glass of sparkling water”, there is also a woman standing with a “sword in hand”.

Both the roles are equally important and needed at the abode. Also, an element of feminism, particularly intersectional, is the fluidity of adjectives used for males and females. Muddupalani has interchanged adjectives multiple times in the text and used them generally to describe males and females.

In spite of popular feminist opinion on Radhika Santawanam, there are some extremely problematic parts in the text with regard to sexualisation, the age of consent and agency, which manifests in marital and sexual relations. These do give rise to concern –

‘Enough sleeping’, I (Krishna) would say.

Feigning anger,

She (Radha) would turn and lie down on her sari.

I would lie at her feet,

Taking her with force,

And she would lie

Languidly on the bed

Like a doll.

…

You sheltered me when I was young,

(Krishna to Radha)

Offering me sweet drinks from your lips,

Embracing me, enticing me, loving me…

While Radhika Santawanam is in parts, subversive, and, in other parts, problematic, the struggle to re-publish the poem, in its entirety, is an important part of the history of feminism and the feminist struggle in India.

What’s surprising is that Kshemendra was a man and Muddupalani was a woman and yet the more feminist of both works, in my opinion, is The Courtesan’s Keeper. While Muddupalani portrays women and their sexuality, Kshemendra shows them in power, in collaboration, in command of their sexuality and more. Time and context do differ, beckoning readers to go back to older texts in order to understand their symbolism and significance, drawing parallels to and lessons for the present.

Also Read: A Feminist Reading Of Baburao Bagul’s Mother: A Story Of Dual Oppression

Jessica Xalxo is a student engaged in the fields of gender, peace, writing and education. A positively empowered individual, she takes on every challenge as a learning opportunity and tries her best to live life intentionally. You can tweet to her @IriscopeX.

Featured Image Credit: Goodreads