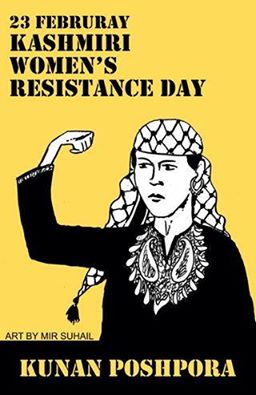

Kashmiri Women’s Resistance Day: Armed Conflict, Militarization and Sexual Impunity

Memory is politics in Kashmir, where erasure (of records, of lives, of histories) and impunity (moral, legal and sexual) are matters of fact and weapons of war. Every year, on 23rd February, the Support Group for Kunan Poshpora, a voluntary Kashmir based women’s network, comes together as a collective along with survivors to stage acts of resistance, remembrance, and reflection, in commemoration of the mass rape and torture of the residents of Kunan and Poshpora, in 1991.

We know the story of what happened that night because the survivors chose to speak out in that moment of terrorizing violence– and have continued to speak for the last 27 years, in the face of vilification, intimidation and devastating silence. We see our job as amplifying their voices, supporting their struggle for truth and justice, and learning from their example.

Kashmir is, as we are often told – the most militarized territory in the world, with an estimated 700,000 state forces, i.e. 1 soldier for every 17 civilian, or an estimate of approximately one male combatant (as in all armed conflicts, combatants are overwhelmingly men), for every 8 women and girls (assuming the sex ratio to be roughly equal). In times of counter-insurgency and warfare, borders are violently marked not just on gendered bodies but are performed in the domains of gender politics, and women’s rights discourses.

Militarization exacerbates both public and private patriarchies, by both state and non-state actors. We, as Kashmiri women, find our selves constantly navigating the complexities of speaking about the everyday violence in our lives as women, without being seen as strengthening statist narratives, within Kashmir. At the same time, the intensive militarization of our lives and how it deeply affects every aspect of our relationships, communities, and identities remain unwritten in ‘feminist’ narratives about gendered violence in Kashmir.

While the horrific intensity of the violence may have ebbed with the decline armed hostilities, the military state’s deeply penetrative hold over the lives and bodies of Kashmiri women continues unabated and takes increasingly complex forms. The recent case of the rape, torture and murder of an 8 year old, of the Gujjar-Bhakarwal nomadic community from the highly militarized borderland district of Kathua and the sexual trafficking of a young woman from Kulgam are two recent examples of the ways in which the security and police state and societal faultiness of caste, gender, community and border geographies coalesce in a militarized society.

The mass rape and sexual torture at Kunan Poshpora is only one unusually well-documented instance of the systematic, deliberate and pervasive targeting of women’s bodies as sites of extreme militaristic violence and reprisals against the Kashmiri insurgency. These acts of violence, which reached a peak in the early 1990s, have gone largely unreported. Physicians for Human Rights and Asia Watch conducted investigations in Kashmir, for their report ‘Rape in Kashmir’ (1993) and documented 15 cases of rape by combatants, during their week-long visit in the ten days preceding it, alone.

Sexual impunity refers to the fact that while the use of sexual violence is pervasive in Kashmir, with researchers from Medicin sans Frontieres reporting 11.5% of the population as having directly experienced sexual violence, many of them repeatedly, police complaints are rarely registered and investigations and prosecutions for these crimes do not take place, at even higher rates. Unsurprisingly in such a highly militarised landscape, the layers of legal impunity in Kashmir are dense and interlocking.

The survivors of Kunan Poshpora have struggled in the District Collector’s Office and Police Station, the State Human Rights Commission, the Sessions and Magistrate’s Courts, the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir, and the Supreme Court of India for 27 years, first to have their police complaint registered, thereafter to have it investigated, then against the closure of their case for the lack of evidence and finally against state appeals on orders of investigations and payment of compensation. Their case is currently in the Indian Supreme Court, awaiting a hearing for the last three years, on an appeal filed by the accused Army Officers, and the State Government of Jammu and Kashmir.

In data collected from Right To Information requests, pertaining to 169 FIRs (police complaints) from 1990 to 2012, relating to sexual crimes by armed state combatants (including police and state-sponsored ‘militias’ Ikhwans), charge-sheets (indictments) have been filed in 29 cases only. Even after the filing of charges, the requirement for government permission for prosecuting state forces (under Armed Forces Special Powers Act, the Army Act and the Jammu Kashmir Criminal Procedure Code) in a trial court means that immunity from legal processes is virtually guaranteed.

In a recent response to a Legislative question, the Indian Ministry of Defence admitted that Jammu Kashmir has only sent 50 cases to the Centre for the required sanction under AFSPA, since 1990, the rest of the thousands of cases filed, being presumably classified as unprosecutable, remaining interminably “under investigations” or “closed as untraced” in the police files. 1 Of these only 3 cases pertained to sexual violence.

The official reasons accorded for the refusal of sanctions to prosecute and for extending the immunity for military actions to sexual crimes, which can never be ‘accidental’ (unlike for instance killings or causing hurt), illustrates the underlying logic of sexualized civilian targeting and rape denial. Thus in the case of Major Arora (FIR no 08/1997) where police investigations charged him with rape, the Ministry of Defence’s reasons for declining sanctions read “The allegation was lodged by the wife of a dreaded HM militant. The lady was forced to lodge a false complaint by ANEs (Anti-national elements)”.

In some rare cases, state forces opt for a court martial by a military court, under martial laws. Court martials and military courts have been universally criticized as failing to respect due process, evidentiary standards and human rights of victims. Court Martials for instance frequently impose minor and less than the legally mandated sentences for horrific crimes. For instance, a sentence of six months imprisonment and dismissal of service, in August 1991, two BSF (Border Security Forces) personnel found guilty of gang rape.

Even these relatively light punishments are regularly challenged and overturned on appeal, as basic procedural safeguards are routinely ignored by Court Martials. Why then, do some survivors continue to struggle to have their day in court, despite these overwhelming odds? Perhaps it is because the law itself provides one form of archiving memory, an acknowledgement of crimes committed.

Legal impunity in Kashmir is underwritten and overlaid by other multiple and disempowering forms of institutionalized and socially entrenched denials of autonomy and co-option of gendered bodies—for instance, the overwhelming militarized and nationalistic nature of Indian coverage of the conflict, in which women are predominantly represented as passive victims of Islamic societal patriarchy, and violence. For the Kunan Poshpora survivors, this has meant that eminent public figures like the head of the then head of Press Council of India, have publically vilified them, misrepresented official evidence and medical documents, and called their versions of what happened that night a “militant hoax”, and suggested that they deserved it.

Our experiences of militarization and sexual impunity in Kashmir, challenge easy binaries of ‘subjugation’ and ‘liberation’. For instance, contemporary media coverage of militarised humanitarian projects, such as those of ‘women’s empowerment’ through compulsory sports programmes and cultural activities, as part of the Counter–Insurgency ‘Operation Sadbhavna’ are often uncritically celebrated by feminists outside of Kashmir, as evidence of Kashmiri women’s liberation from societal constraints.

There is a little reflection on the militarised context or the co-option of our lives and communities into the machinery of the “hearts and minds” warfare. Who really is the “me” in the #MeToo ‘global’ ‘sexual revolution’? What kinds of sexual speech and archived truths are permissible to women whose very bodies represent the jagged edge of what it means to be “us”, as nationally identified citizens? On this Kashmiri Women’s Resistance Day, we urge for a broader conversation on questions of women’s bodies, impunity and erasure as processes, and militarism as an ideology, in which we are all implicated.

This statement is written by ‘Support Group for Justice for Kunan Poshpora’.

Featured Image Credit: Mir Suhail

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.