At the age of nine, after watching a particularly vague sanitary napkin advertisement, I yelled to my mother, all the way across the room, “What is a period?” My mother looked at me, her face stern. It was the face I saw often, the face of disapproval, the face that told me I am not to speak of the current subject anymore if I don’t want to get into trouble. My grandparents who were in the same room continued watching television, without shame or disgust.

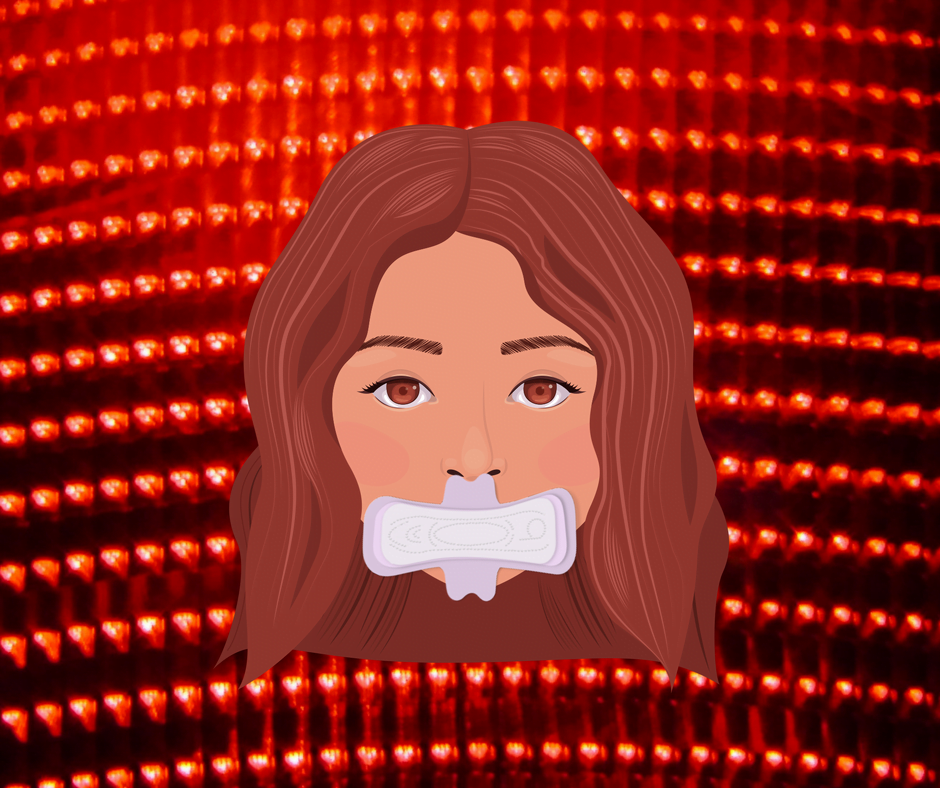

A few minutes later, my mother called me to the kitchen and told me I am never to ask in front of an audience what a period is. She said it is something you don’t speak of in front of men. I didn’t see why, but I assumed it must be dirty if we had to protect men from it. Although she went on to tell me what menstruation is, she also did tell me it was our dirty little secret – the dirty little secret of all women. Like she would go on to tell me four years from that day that our bodies were our dirty little secret too.

I wouldn’t want you to judge my mother too harshly, she was brought up in a culture of shame. She tries to eliminate her biases and to see things without the lens of ingrained sexism and systematic oppression. But there are things her systematic and five-decade-long conditioning doesn’t allow her to see.

I knew of the women who didn’t bleed and I wished to live the shame-free life I thought they lived.

I had my first period when I was 13. I sat in my bathroom bleeding for over an hour, in shock. I didn’t want this very embarrassing, wrong-to-speak about thing happening to me. Just the year before, I had seen a classmate cry because she had her first period. She wouldn’t tell me why, but I could sense her shame and now it was my shame.

I eventually eased into my period, but I still carried the weight of shame. A few months later, the girls of my class were asked to come to the library in a single-file line. I was anticipating something fun, but they were going to teach us about menstruation. The first thing they told us was that we weren’t to discuss this with the boys of our class – this was a reminder we were given every three minutes for the next 15 minutes.

Now, I did want to learn more about menstruation, but since all of us were taught it was shameful, I knew paying close attention would mean endless mockery. You don’t want to be the only 13-year-old interested in listening to ‘gross’ things. So I didn’t pay attention, just to make sure my friends knew I was on the same page. I repeatedly said how gross this discussion is.

A year from then, as my crippling shame remained, I wished I never had my period. I knew of the women who didn’t bleed and I wished to live the shame-free life I thought they lived. I thought not having my period clearly meant not having to deal with the shame it brings. I was wrong, though. Women are shamed for bleeding, but they are shamed more for not bleeding.

Also Read: Period Piece Official: Menstruation Through The Ages

That brought me to the question, to bleed or not to bleed? If you ask patriarchy for the answer, then there is no way to win this. Bleeding is shameful, not bleeding is a disgrace. Then again, if you ask patriarchy for answers relating to women, women can never win.

Patriarchy wasn’t devised to enable women to win. The failure of women is patriarchy’s win. Although the right answer, as I learnt four years after I had my first period was surprisingly simple, the answer was to not be ashamed of our own anatomy, whether we bled or not.

The shame we share as women is not something that binds us together. It isn’t something that we should romanticize, it isn’t a symbol of our sisterhood. It’s a tool of oppression – not a tool we devised, but a tool we have begun using, in the name of culture, not realising we are accessories in our own systematic oppression.

We bleed or we don’t, one of those is the truth of our bodies, a truth we shouldn’t have to protect anyone from. Menstruation in itself is no different from any of the other things our body does, but the disgust surrounding it comes from the fact that it is only exclusive to women. Period-shaming women is a patriarchal sport. Anything exclusive to women becomes ‘gross’ and becomes another reason to oppress them.

Women are shamed for bleeding, but they are shamed more for not bleeding.

A very large part of my 5+ years of menstruation experience hasn’t been about me, it’s been about men. It has been about protecting unsuspecting men from the horrors of the female anatomy. I don’t protect men from the bloody reality of my vagina anymore and a lot of them seem okay with it.

My grandfather who my mother was protecting when I asked at age nine what menstruation was, used to freely speak of menstruation, bought menstrual products with ease and watched advertisements for sanitary napkins without flinching or the slightest bit of discomfort. I asked my mother nine years after the incident that if he knows if he is comfortable.

Her attempt at protecting him was futile, so why bother when she knows of the inevitable futility of her attempt? She said she doesn’t know. I know she sees the futility of her attempt, in fact, she even sees it’s asininity, but she isn’t a changed woman after this dialogue. She will continue to protect men because this culture of period-shaming was passed down to her. Just like it was passed down to the rest of us and most of us will pass it down to our children.

Also Read: Divided Feminism And Underlying Patriarchy Of Reproductive Health Concerns

About the author(s)