When Sabyasachi Mukherjee recently suggested that young women who can’t tie a sari should be ashamed of themselves, women across India justifiably called out the entrenched patriarchy in his comment. As Assamese actor Rajni Basumatary, pointed out, Indian clothing for women includes bakus, chaniya cholis, mekhla chadors, pavadas (and ‘half saris’), salwar kameez, churidaars and (dare I say) Indo-western wear: palazzos, harem pants and the ubiquitous kurtis worn with skirts, jeans and shararas as well as Western-style skirts and dresses (traditionally worn by Goan and Anglo-Indian women) making it difficult to argue that there is only one form of “Indian dress”.

To be fair, the designer apologised swiftly and acknowledged the misogyny (and somewhat reductionist view of Indian clothing) in his remarks. But his controversial comments got me thinking about an incident that my friend N. narrated some years ago.

Having migrated from New Delhi to Riyadh, N had taken to wearing an abaya and shela (scarf) in public as per Saudi Arabian laws. Covering herself in public took some getting used to since N had spent most of her life in Delhi wearing jeans, kurtas, salwar kameez, skirts and saris. Like most young women who studied in Delhi in the 1990s, N and I tended to choose our clothes every morning with the hope of mitigating the sexual harassment we faced in Delhi’s notorious public buses – a somewhat pointless exercise as artistic research projects by movements such as Blank Noise have revealed.*

When she migrated to Saudi Arabia, N learnt to bear with the scrutiny of the ever-vigilant Saudi police who are instructed to see that women wear their abayas ‘properly’ in public (without accidentally letting their covering slip to expose their hair or skin). But she was always glad to remove it when she entered the somewhat upscale expatriates’ enclave where she lived.

N and I tended to choose our clothes every morning with the hope of mitigating sexual harassment.

Her neighbours in the gated enclave were primarily European and consequently dressed in much lighter clothing that they considered appropriate to Saudi Arabia’s hot weather. Shorts, sleeveless dresses and halter neck blouses were common attire in the expats’ enclave where the Saudi Arabian government does not impose sartorial rules.

“How nice it is,” N thought to herself one afternoon as she entered the gates of the enclave and walked towards her front door, “to be free from the scrutiny of policemen zealously looking for the appearance of a few scandalous inches of female skin“. To her surprise, her ruminations were interrupted by the security guard who had just let her in.

Also Read: The Bra Strap: Normal Piece Of Clothing Or State Secret?

“Madam,” he requested running after her, “could you please take off your abaya immediately?” Apparently, the (predominantly European) management of the enclave was keen that no abayas be seen within its cosmopolitan environs, the only space in Saudi Arabia where they were free to practice their culture.

Being neither Saudi Arabian nor European, N found herself adapting to the conflicting cultural norms of the city as well as the expats’ enclave and in both instances, decisions about how her body must appear in public were taken and enforced by men. “Women’s clothing in Saudi Arabia,” she said to me on a visit home, “is men’s business.“

Women’s clothing is men’s business not only in Saudi Arabia but in India, France and the USA as well. In India, women learn that quite early. I was in high school when the male principal of the secular co-educational school where N and I studied made a casual reference to the girls’ uniforms, prescribing the exact length of our skirts – two centimetres below the kneecap – while simultaneously reiterating that when it comes to clothes, women can never be right.

Anything longer, he kindly explained, would make us look like ‘behenjis’ (frumps) and anything shorter would make us seem ‘fast’, while those whose skirts were indeed two centimetres below their kneecaps would be labelled the principal’s ‘chamchis’ (sycophants). And yes, after all these years I still remember his speech, almost verbatim.

His remarks were welcomed with hoots of laughter from the boys and nervous giggles from the girls while the teachers tried to hide their disbelief. To my knowledge, nobody called out his sexism. Even as teenagers we were used to being objectified.

N didn’t need to go to Saudi Arabia to learn that women’s clothing is men’s business.

Over twenty-five years ago – and we might (wrongly?) presume that twenty-five years ago society was much more conservative – it was acceptable for a male principal of a government-aided school to publicly discuss his female students’ uniforms in a sexualized manner, implicitly inviting his male students to join him in the joke. But little has changed. Is it any surprise then that sexual abuse still occurs in many of our schools or that educational institutions still police young women’s clothing?

N didn’t need to go to Saudi Arabia to learn that women’s clothing is men’s business. I didn’t need to hear about Sabyasachi’s remarks at Harvard to know how women’s bodies become the sites on which powerful men write national and community identity by prescribing their attire. We didn’t even need to wait till we took our first solo trip on a public bus as college students to know that our clothes offer a source of endless amusement to the men around us.

All N and I had to do was pick up our books and go to school (right here in India) where our principal engaged in sexist humour at our expense. Our parents sent us to school to learn lessons for life and we certainly learnt an important one at the school assembly that day.

Also Read: How Did This Professor From Kerala Confuse Breasts With Watermelon?

*When Blank Noise founder Jasmeen Patheja called for women to bring clothes that they had worn when they were harassed as part of the Never Asked for It Project, such a wide variety of clothes arrived that it became clear that women’s choice of attire is unlikely to protect them from harassment.

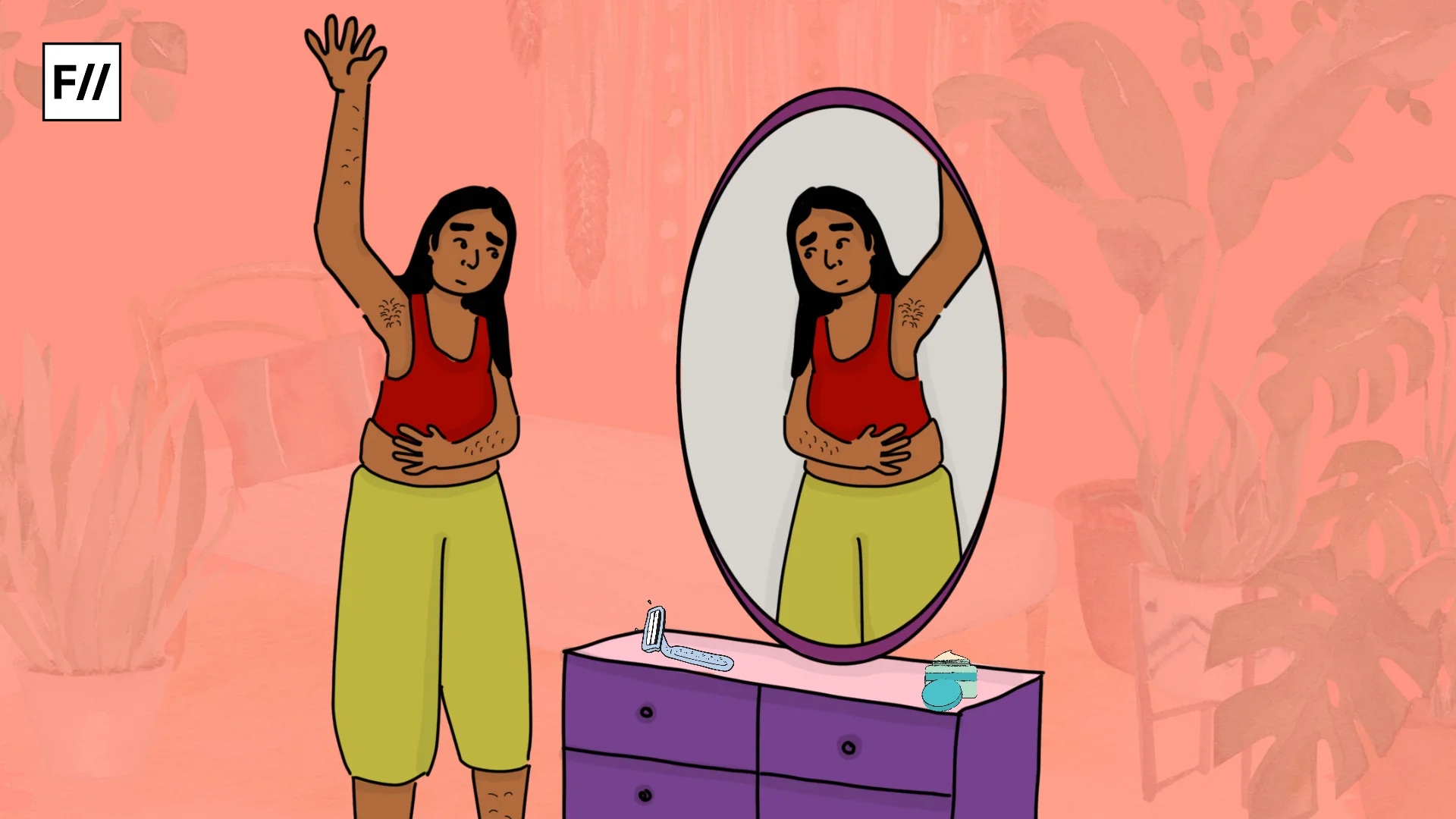

Image Credit: Catholic Modesty

About the author(s)

Jyothsna Latha Belliappa has a PhD in Women’s Studies from The University of York, UK and is interested in issues of gender, work, education and personal life. She divides her time between teaching, writing research and long meandering walks in nature.