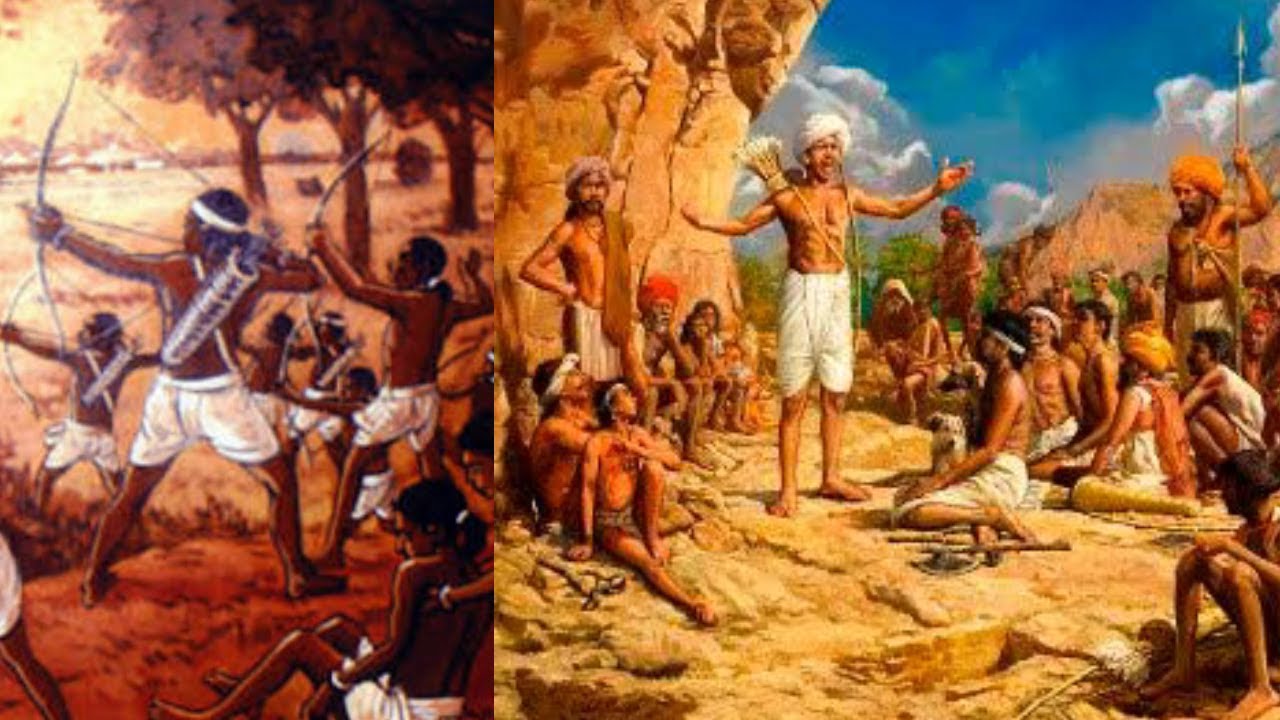

The indigenous people’s movements in colonial India were organised with strategies of guerrilla warfare and armed revolts. The movements were anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist in nature.

The fights to retain age old practises that were disturbed by colonialism were dominant causes of the movements. The traditional practises of tribes in India were severely affected due to the rise in the systems of indentured labour, taxation policies and immigration of mainland traders and workers into the tribal belts.

The nature of the indigenous people’s movements vary and each have their own significance. The various trajectories of the movements are peasant rebellions, movements for self-determination, identity and ethnic nationalist movements. This article covers a few of the prominent indigenous people’s movements colonial and post-colonial in India.

1. Munda Rebellion, led by Birsa Munda

The movement is famously called ‘Munda Ulgulan‘. The movement was led by Birsa Munda and is a renowned 19th century tribal revolt in the Indian Subcontinent. The movement took place in the South of Ranchi from 1899-1900.

The khuntkattidar land revenue system of the Mundas was replaced with jagirdars and tikhadars as merchants and money lenders in the tribal belt. This process of land alienation had begun long before the advent of the British. But the establishment and consolidation of British rule accelerated the mobility of non-tribal people into tribal regions. The incidence of forced labour or beth begari also increased dramatically. Unscrupulous contractors had turned the region into a recruiting ground for indentured labour.

Born in 1875 to a family in the Munda tribe, Birsa Munda, referred to often by

Jharkhand’s tribal residents as “Birsa Bhagwan”, led what came to be known as “Ulgulan”

(revolt) or the Munda rebellion against the British colonial feudal state.

In 1894, Birsa began to inspire people by combining religion and politics. The flames of the struggle spread to 550 sq. miles in the Chota Nagpur region, with several fights and wars between the tribes and the British.

On February 3, 1900 Birsa Munda was caught. Severe cases were filed against him and his comrades. On June 9, 1900, Birsa Munda became a martyr in Ranchi’s Central Jail, aged 25. The Britishers declared that he died of cholera.

The revolt allowed the British Indian Government to enact Chotanagpur Tenancy Act, abolish Beth Begari and recognize the existence of khuntkatti system. Birsa Munda became a lengend to the tribes of Chota Nagapur and for Bahujan groups in India. He is a symbol of the anti-feudal, anti-colonial struggle of that time.

2. Bodoland Movement

The Bodos are the most significant part of the vast Bodo-Kachari, an ethnolinguistic group of Mongoloid origin living in Assam. The tribal groups are the indigenous inhabitants of Assam and it was the Bodos who first created culture and civilization in the Brahmaputra Valley.

They have also maintained their distinct ethnic identity. They ruled vast territories of North East India, parts of Nepal, Bhutan, North Bengal and Bangladesh. For centuries, they survived sanskritization. However, in the 20th century, they had to tackle a series of issues such as illegal immigration, incursion of their lands, forced assimilation, loss of language and culture.

The same period has witnessed the emergence of the Bodos as one of the leading tribes in Assam to pioneer the movements for safeguarding the rights of tribes in the north east. The Bodo movement is a product of the socio-economic and historical milieu of Assam. The movement has gradually grown for decades.

Dominant caste aggression, the dispossession of land and natural resources, loss of ethnic and cultural identities, the uneven process of pre and post-colonial development accompanied with narratives of alienation, disempowerment and poverty of Bodos are the various causes of the Bodoland movement.

The Bodo movement can be divided into four phases. The first phase comprises the time period between 1933-1952 which was largely a phase of political awakening. This phase had also witnessed the formation of All Assam Plains Tribal League. The major demands of this phase is of more electoral participation and a separate electoral system.

The second phase was between 1952-1967, which witnessed the formation of the Bodo Sahitya Sabha. This period comprised the assertion of linguistic identity due to the threat posed by the dominant Assamese community.

The third phase of 1967-1986 constitutes the demand for political economy. The phase had witnessed the demand for a union territory called Udayachal. The All Bodo Students Union was formed on 15th February 1967.

Phase four occurred between 1986-1992, which gave rise to the demand for a separate statehood. The demand to divide Assam into 50-50 was the echo of the movement during this period. The period also witnessed the rise of a militant organisation called Bodo Security Force (BdSF) on October 3, 1986.

The last phase of the Bodo Movement was started in 1993 with the post-Bodo accord which failed to meet the expectations of Bodos. This period has also witnessed the extremist activities and protests of BdSF.

The movement post-2003 was not a part of the mainstream until the declaration of the formation of the separate state of Telangana. The demand for Bodoland is a continuous one that is left unaddressed. It is the responsibility of Government of India to look into this issue and address the problem rather postponing.

Also Read: Cultural Appropriation Of The Dongria Kondh By Amoh By Jade

3. Niyamgiri Movement

The Dongria Kondh tribe of Odisha resides in Niyamgiri. The mountain range Niam Dongar is also a place of worship for the Dongria Kondh. Niam Dongar is regarded by the tribe to be the abode of their divine god, Niyam Raja (The King of Law).

Niyamgiri is the source of livelihood for the Dongria Kondh. The peaceful existence of the tribe, where they practised sustainable agriculture based on forest produce, was placed under threat on June 7, 2003.

Vedanta signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Government of Odisha for the construction of an alumina refinery, along with a coal-based power plant in the Lanjigarh region of the Kalahandi district. For the purpose of obtaining bauxite for this alumina refinery, the Vedanta-owned Sterlite Industries also entered the picture, with plans to construct an open-pit, bauxite mining plant at the top of the sacred Niyam Dongar mountain.

The Niyam Dongar acts as a sponge that soaks up the monsoon rains and then holds deposits of water through the hot summer months. These reserves ensure the continuous flow of perennial streams across the Niyamgiri hills, which are vital for the Dongria Kondh as they provide water for drinking and irrigation purposes.

Any mining activity at the top of the mountain would cause these perennial streams to dry up. It has been observed that Vedanta also played foul in acquiring environmental clearance from the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF). Further, Vedanta’s dubious methods for construction of the alumina refinery were being ignored by the MoEF.

This allowed three petitioners to file applications with the Central Empowered Committee (CEC), appealing to the authorities to look into Vedanta’s suspicious environmental clearances. When the case reached the Supreme Court, the court refused the CEC recommendations which sided with the Dongria Kondhs. As an aftermath of the decision by the Supreme Court, there were protests and demonstrations not only by the Dongria Kondhs but also from progressive circles in the national and international arena.

The movement became victorious when MoEF set up an experts committee. The team of experts, in their March 2010 report concluded that Vedanta’s proposed bauxite mine would be detrimental to the existence of the Dongria Kondh; a consequence which was too serious to ignore.

Finally, 12 Gram Sabhas (village councils) were chosen by the state government to make the crucial decision. In the three months after the Supreme Court ruling, amidst heavy police presence and persistent threats from Vedanta, 11 Gram Sabhas voted against the mining project and on August 19, 2013, the 12th and final Gram Sabha delivered a resounding ‘No’.

In January 2014, the MoEF, which had earlier aided Vedanta’s invasion of Niyamgiri, crushed the company’s mining ambitions by completely rejecting the project. In this sensational decision and in gaining coverage in international media, the Dongria Kondh emerged victorious in the decade-long battle against Vedanta.

4. Santhal Rebellion

The Santhal Rebellion is one of the first indigenous peasant upsurges in the first half of the eighteenth century. The Santhals were the original inhabitants of the Santhal Paraganas in erstwhile Bihar, within the territories of ‘Domin-i-ko’, where they practised revenue-free land holding mechanisms.

The Pakur Raj family who were local zamindars were responsible for imposing taxation and land revenue on the Santhals. The Santhals began to be exploited by the usury practices of the Mahajans, who came from Bengal, Bihar and other provinces of India.

The railway network began to spread from the fourth decade of the nineteenth century, in order to facilitate the process of marketing machine-made goods from England. The Santhals were exploited as cheap labourers in the process of expanding the railways.

The Santhal Rebellion was started in 1850 and called Hul (a movement for liberation). It was headed by four brothers of the Murmu clan – Sidhu, Kanhu, Chand and Bhairav and their two sisters Phulo and Jhano.

On 7th July, 1855, a huge number of Santhals assembled in a field in Bhognadih village. They declared themselves free and took an oath under the leadership of Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu to fight till their last breath against the British and their agents. The Santhals were passionate and fierce warriors but they didn’t stand a fair chance against the firearms used by the British East India Company.

The Santhal Rebellion was subdued by cruel repression unleashed by the English rulers and their local agents. Yet it left behind an enduring legacy of resistance, where the Santhal rebels, both men and women, were supported by the non-dominant caste Hindu inhabitants of the Santhal Pargana region and the adjoining districts of Bengal.

This legacy was subsequently reflected in the peasant movements undertaken in Bengal, including the Tebhaga Movement, till the end of British rule in India. It also inspired the movement for the separate state of Jharkhand led by Shibu Soren.

5. Komaram Bheem’s Revolt against the last Nizam

During the Nizam’s rule in Hyderabad, the government imposed unbearable taxes. The exploitation and atrocities of local zamindars was rampant on the indigenous people of the region. In the midst of this, Komaram Bheem (the legend of the Gonds in Telangana) launched a massive agitation against the state in the forest-based villages or Gondu Gudems of Adilabad.

Jode Ghat was the centre of his activities. Bheem organised a militant struggle with a guerilla army. The movement continued from 1928 to 1940. Bheem proposed a plan of action in order to declare the region as an independent Gondwana state for Gonds.

The uprising threatened the government, who then sent agents to offer Bheem material possessions in order to give up the struggle. An uncompromising leader, Bheem refused government offers of personal possession and continued his struggle.

He stated that his guerrilla army stands for justice and freedom. He gave the famous slogan of ‘Jal-Jungle-Jameen’ during the movement. Komaram Bheem attained martyrdom in a conspiracy plotted by the Nizam on September 1, 1940.

Also Read: 5 Adivasi Women Activists We Should Know About

This is by no means an exhaustive or representative list. Suggestions to add to this list are welcome in the comments section.

Featured Image Credit: Sabrang India

About the author(s)

Manohar Boda is a Research Scholar based at JNU - New Delhi.