Because my grandmother’s hours

were apple cakes baking,

& dust motes gathering,

& linens yellowing

& seams and hems

inevitably unravelling

I almost never keep house

though really I like houses

& wish I had a clean one.

Because my mother’s minutes

were sucked into the roar

of the vacuum cleaner,

because she waltzed with the washer-dryer

& tore her hair waiting for repairmen

I send out my laundry,

& live in a dusty house,

though really I like clean houses

as well as anyone.

I am woman enough

to love the kneading of bread

as much as the feel

of typewriter keys

under my fingers

springy, springy.

& the smell of clean laundry

& simmering soup

are almost as dear to me

as the smell of paper and ink.

I wish there were not a choice;

I wish I could be two women.

I wish the days could be longer.

But they are short.

So I write while

the dust piles up.

I sit at my typewriter

remembering my grandmother

& all my mothers,

& the minutes they lost

loving houses better than themselves

& the man I love cleans up the kitchen

grumbling only a little

because he knows

that after all these centuries

it is easier for him

than for me.

– Erica Jong ‘Woman Enough‘

I first read this poem on a wintery evening when my friend Sanja, who shared my student office, put it up on our corkboard. Sanja had just finished negotiating tenuous childcare arrangements so that she could spend a few extra hours working on her thesis and we both smiled as we read it.*

The poem reminded me of the beautiful old house in which I grew up, of my grandmother scrubbing the floor on her knees and ‘brassoing’ the lamps before Diwali, of a kitchen table laden with sweets: pink diamond shaped coconut barfi, chirotis dusted with castor sugar, holige (puranpoli) and nankatai.

I was born in the 70s, a decade in which women across the world questioned and resisted conventional notions of marriage and motherhood, fought their way into business and parliament, re-imagined the organisation of higher education. Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique was published in America a decade before my birth. The Towards Equality report was written in India around my second birthday.

My grandmother was in her teens when Gandhi passed through the small Gujarati town where she lived and she walked to the station to see him. She read revolutionary tracts along with her sisters, participated in the freedom movement, worried about the Second World War and insisted on finishing school before she married.

On her bookshelf sits a wedding present from a friend, a faded hardbound volume of Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India. “To the couple who are about to begin their lives in independent India” says the card inside.

I am aware that choice is a privilege: a privilege that came to me because my mother’s generation fought for it.

My grandparents married in the summer of 1947. My mother was born a little over a year later. My granny settled into domesticity and became a 1950s housewife – proud of her organisational abilities, zealous in keeping her home tidy, a competent seamstress, a painstaking cook, a strict and loving mother who brought up her children according to the ‘scientific principles’ recommended by second-hand imported copies of Women’s Weekly that she bought from the newsvendor down the road.

The home she created was my haven as a young child and all my adult life I have tried to re-create it with limited success. My relationship with cooking changes from week to week but home-making has been a more consistent passion: cleaning, tidying, arranging, organising.

Like Erica Jong, I love clean, beautiful, welcoming houses. Like Jong, I also love to write. I love the tapping my fingers in a rhythmic tattoo as I type. I love going out to work, meeting interesting people, debating ideas, organising projects. Like every worker, I’m often exhausted and frustrated by my work. Like Jong, I wish I could be two women. I wish the days could be longer. But I’m not and they aren’t. I have to choose.

While I hate choosing, I am aware that choice is a privilege: a privilege that came to me because my mother’s generation fought for it. They opened up spaces for me in professional and public life. They refused to accept that their daughters would be confined at home gathering dust motes. By creating a space for me in the world, they enabled me to come home, not to drudgery, but to pleasure.

As a feminist, I have cooked and cleaned, often with irritation and exhaustion but also with joy and fulfilment. I’ve learned that when women have freedom, when men partake of our responsibilities, cooking and home-making can be feminist acts, drenched in love even when they exhaust us.

Also Read: Are Families Above Women?

Love, care, exhaustion, passion – feminist words, feminist feelings which save the world and keep it sane. Feminists extend love from the home to the world and back again. It’s no accident that a major feminist cause of the last century (and this one) has been the right to love (whoever we wish to, irrespective of caste, creed, colour or gender).

In the same winter when Sanja shared Jong’s poem with me, I mentioned to my thesis supervisor, Haleh, that I was missing home. She invited me over for a simple meal of soup and homemade bread, warming both my hands and my heart, before asking me to submit the next chapter of my thesis.

Haleh knew that the best sustenance for intellectual work is through attention to what we conventionally call ‘the soul’. She finds no contradiction between her love of cooking and her deep commitment to feminism. She takes as much joy in her life as a mother and grandmother as she does in teaching, writing and fighting for women’s rights.

Haleh is an activist, parliamentarian, scholar, homemaker (often all at once) and while she is regularly short of time, she’s never short of love. She extends this love to her students – sharing books, meals, advice and contacts, generously and unstintingly, years after we have graduated.

I have learned from my grandmother, Haleh and from other feminists the importance of nurturing: oneself and others. Food is the most primaeval form of nourishment one can extend. Over the years I have cooked and shared meals with many feminist friends, both male and female.

Feminists extend love from the home to the world and back again.

I have found that the friendships cemented in the kitchen between dicing, chopping, stirring and tasting are strong and tenacious: tightly knitted together with vigorous debate, delicious gossip and shared laughter, these friendships stand the test of time – and result in new ideas for teaching, research and activism.

If my grandmother’s hours, once the Second World War and the movement for Indian independence ended, were indeed taken up with apple cake baking and dust motes gathering, my mother’s generation gave me the gift of independence. They gave me the choice of not only cleaning my house but also of paying my mortgage.

They fought for my right to do so and in the bargain, increased my responsibilities manifold. So while it is not easy to live by my wits, or my keyboard, it is infinitely better than tearing my hair out waiting for repairmen.

Because of the 70s feminists, I can come home to a clean or dusty house depending on what else is happening in that week or that month, how sound my finances are and how demanding my employer is. I can go to the kitchen to bake apple cakes or microwave leftovers but it is still a choice, however constrained by circumstances. I can feel the spring of the keyboard under my fingers as I dream of pink coconut barfis that I just might have the time to make next Diwali.

Also Read: Why Do Single, Independent Women Still Scare People So Much?

* Sanja went on to write a highly acclaimed thesis on Muslim women’s identities while mothering two wonderful young feminist boys and continuing her work as a peace activist.

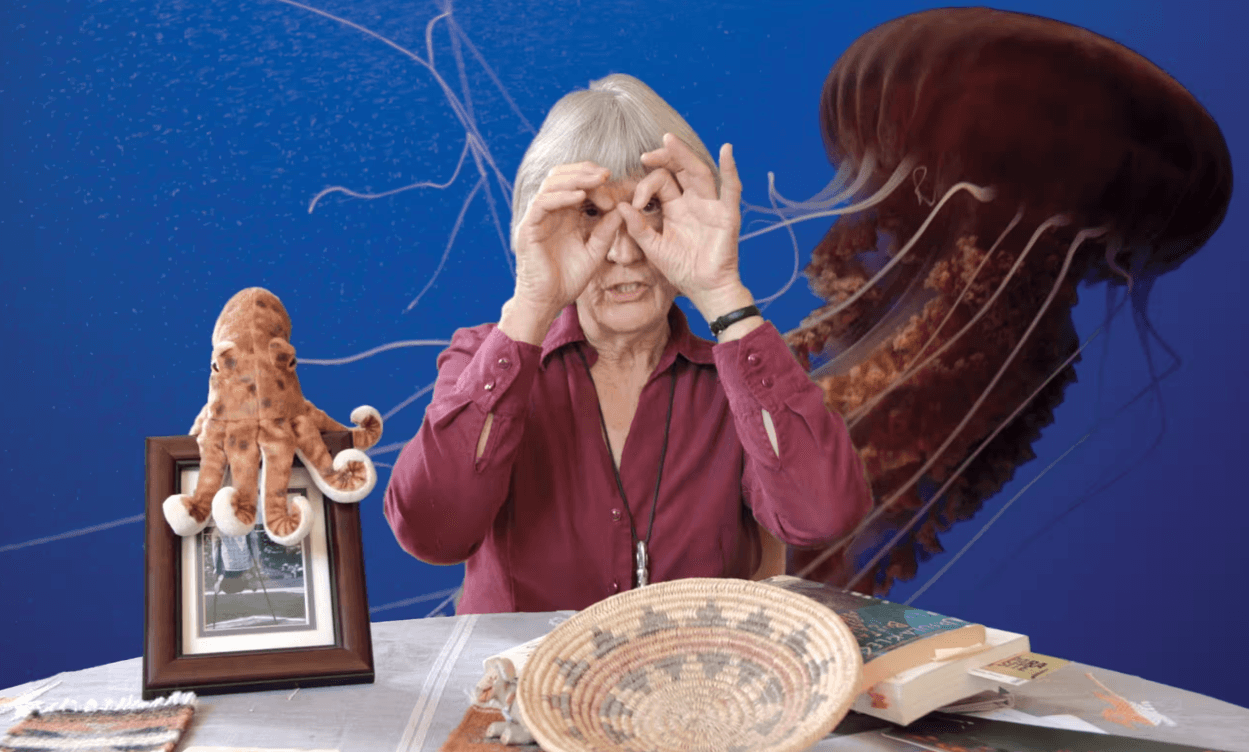

Featured Image Credit: Women’s Web

About the author(s)

Jyothsna Latha Belliappa has a PhD in Women’s Studies from The University of York, UK and is interested in issues of gender, work, education and personal life. She divides her time between teaching, writing research and long meandering walks in nature.