Harry Potter and Percy Jackson were household names for me when I was growing up. It was rare for any child in middle and high school to have not heard of J.K. Rowling’s wizarding world.

If a magical school was not their cup of tea, then they had at least heard of Lord of the Rings, or taken a journey through the C.S. Lewis’ wardrobe to Narnia. In fact, by the time we were sixteen years old, some of us were even delving into George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, an epic universe we now associate with HBO’s Game of Thrones.

Yet, in all those years, I can never remember discussing any Indian authors who wrote stories directed at teenagers and young adults. I remember buying the first day-first show tickets for The Hunger Games and anything from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but no similar hype for any content produced by authors of colour – specifically, Indian authors.

It is easy to argue that there were certainly some books that cropped up that were produced by desis – both here and the diaspora. Chetan Bhagat was a hot favourite. But his books were still directed at a college-going/techie-age group with struggles that were difficult to relate to for teens (even then, he did not win out against the John Green fever, never mind that both are problematic, male chauvinist authors who wrote manic pixie dream girl characters).

When asked to recommend something deeper, people often jumped to Salman Rushdie. Of course, this was mainly because the controversial nature of his work created an appeal, more than the post-colonial commentary in the content, which is what actually makes it a good read.

What was the reason behind this lack of diverse fiction? Or, rather, the reason behind putting white characters (written by white authors) on a pedestal for audiences that were neither white nor could entirely relate to these characters that were becoming both idols and ideals for young adults across the globe?

Some call diversity a “buzzword”, defining it either as an attempt to boost sales and publicity or as a checklist item to cross off by factory producing two-dimensional token characters. Unfortunately, this is not just the case while discussing diversity outside of India.

Is diversity simply introducing dialogue-less, personality-lacking side characters who fit stereotypes?

Even within upper-middle-class Indian circles, often the demographic that has the best access to the elite world of publishing and literature, there is a dismissal of the need for diversity. Stories of minorities are often seen as “unnecessary” and “beating around the bush”. The concept of promoting own-voices is misconstrued as “silencing” other voices.

“Why do we need stories of people downtrodden and beaten? How are we going to move forward as a nation if we keep writing/creating stories of people in misery? We need to learn from Western authors!” – is the rhetoric heard from the privileged classes that are fortunate enough to not have the same nature of tales to tell. It’s a rhetoric that encourages proximity to anything that comes from the West, the good and the bad, instead of searching for important tales to shout from our own communities and culture.

But what is diversity? Is diversity simply introducing dialogue-less, personality-lacking side characters who fit stereotypes? Is it praising privileged authors for doing the bare minimum? Or is it amplifying and signal boosting the voices of those who know how to best tell stories of struggles specific to certain demographics? Is it giving ourselves a pat on the back for liking the one, token character written by a white author, or is it actively calling out the way own-voice authors are treated by publishing industries?

One of the biggest problems is that when criticism about lack of diversity crops up, people who often stick to mainstream pop culture see it as a personal attack on their tastes. Make no mistake – there is nothing wrong in consuming mainstream culture, especially since we’ve only recently begun to incorporate it so easily into Indian media.

Unlike the early 2000s, when everyone had to wait 2-3 years for new seasons of American and British shows or even resort to downloading them illegally, consuming Western media has become extraordinarily easy in today’s Netflix and Amazon Prime age. So, naturally, there is going to be a higher demand and an audience for it.

Also Read: India’s Graphic Tale – 5 Graphic Novels By Women We Should Know About

Not to mention, there is nothing wrong with liking this content – whether it’s a critically acclaimed movie or a trashy soap opera, the criticism is not coming from a place of superiority or judgement. Instead, it needs to be seen as an attempt at avoiding stagnation.

I recently witnessed a debate on both Twitter and Tumblr (not for the first time, sadly) between multiple white readers and readers of colour about how far criticism on problematic aspects needs to be taken, and whether it’s okay to judge readers for only reading white authors. Naturally, the debate started because the initial takeaway from the privileged side (none cishet but predominantly white) was that anybody who reads solely white authors’ works has a level of guilt to bear, which is not fair. However, when this privileged take on things was pointed out, many toes were stepped on.

The fact is that while there is no shame or judgement towards anybody who reads mainly cis-het white authors, the responsibility of introducing diverse fiction does not rest solely on the shoulders of said writers. Publishing industries, like any capitalist industry, thrive off sales, reviews, and reader opinions – and the facts are that books written by authors of colour are not making the same kind of money, nor are they receiving the same level of attention.

The issue isn’t the lack of diverse fiction – it’s that these diverse voices are not given the same treatment. As a result, it’s white authors who receive the hype, and consequently filter into foreign markets, India included.

It is not surprising that when I tell people I wish to become an author, they are encouraging until the moment I mention fantasy and young-adult as my genre of interest. The questions that pop up range from “Oh, like the Game of Thrones stuff?” or “Is there even an Indian market for it?” to even, “Are you sure you want to write that? It might not sell coming from you. What fantasy will you set in India?”

Aside from the pre-existing bias against fantasy, sci-fi and young-adult as serious genres of literature, there is an added layer of scepticism attached to Indian authors – a discouraging notion when it comes from Indian audiences themselves. It is a notion that plays into the cycle of consuming white voices and pushing down our own – after all, if we don’t encourage and promote these authors then how will they take the same place in local and global markets that white authors have?

criticism based on lack of diversity needs to be seen as an attempt at avoiding stagnation.

Most of us – millennials and a significant number of Gen Z kids, especially – have grown up reading about tales of children in communities we don’t entirely relate to, with different life experiences due to the privileges they may or may not have. With current talk of the importance of diversity, we’re stuck under the double-edged sword of the single-story danger.

On the one hand, if we don’t prioritise stories from our own communities then we risk silencing ourselves. On the other, since Western media is also diversifying itself, we risk losing out on the stories from minorities portrayed in Western media and continue living with beliefs that have been ingrained in us from outdated, problematic sources.

An attempt at resolving this issue is not as difficult as it may seem. It’s as simple as supporting (promoting, reading, buying, reviewing) diverse content creators as much as one might support privileged ones, and ensuring that all stories (especially own-voice stories) are heard in the same way. There is an abundance of Indian authors who write for multiple genres, including books relevant to desi audiences across the world, including works that young adults and teenagers are guaranteed to not only enjoy but take away from.

Take, for example, Rick Riordan Presents. Famed for his Percy Jackson series and for re-introducing Greek, Roman, Norse and Egyptian mythology to middle-grade readers, Rick Riordan’s imprint with Disney-Hyperion is an attempt to publish more middle-grade stories on diverse mythologies from underrepresented authors writing about their own culture and introducing it to mainstream young-adult markets.

Using their privilege to amplify the voices of others, the imprint has already acquired three titles – Aru Shah and the End of Time by Roshani Chokshi (Hindu mythology), Dragon Pearl by Yoon Ha Lee (Korean mythology), and Storm Runner by Jennifer Cervantes (Mayan mythology). This imprint isn’t Roshani Chokshi’s first run at introducing Hindu mythology to audiences. She has also written The Star-Touched Queen series, which also delves into myths.

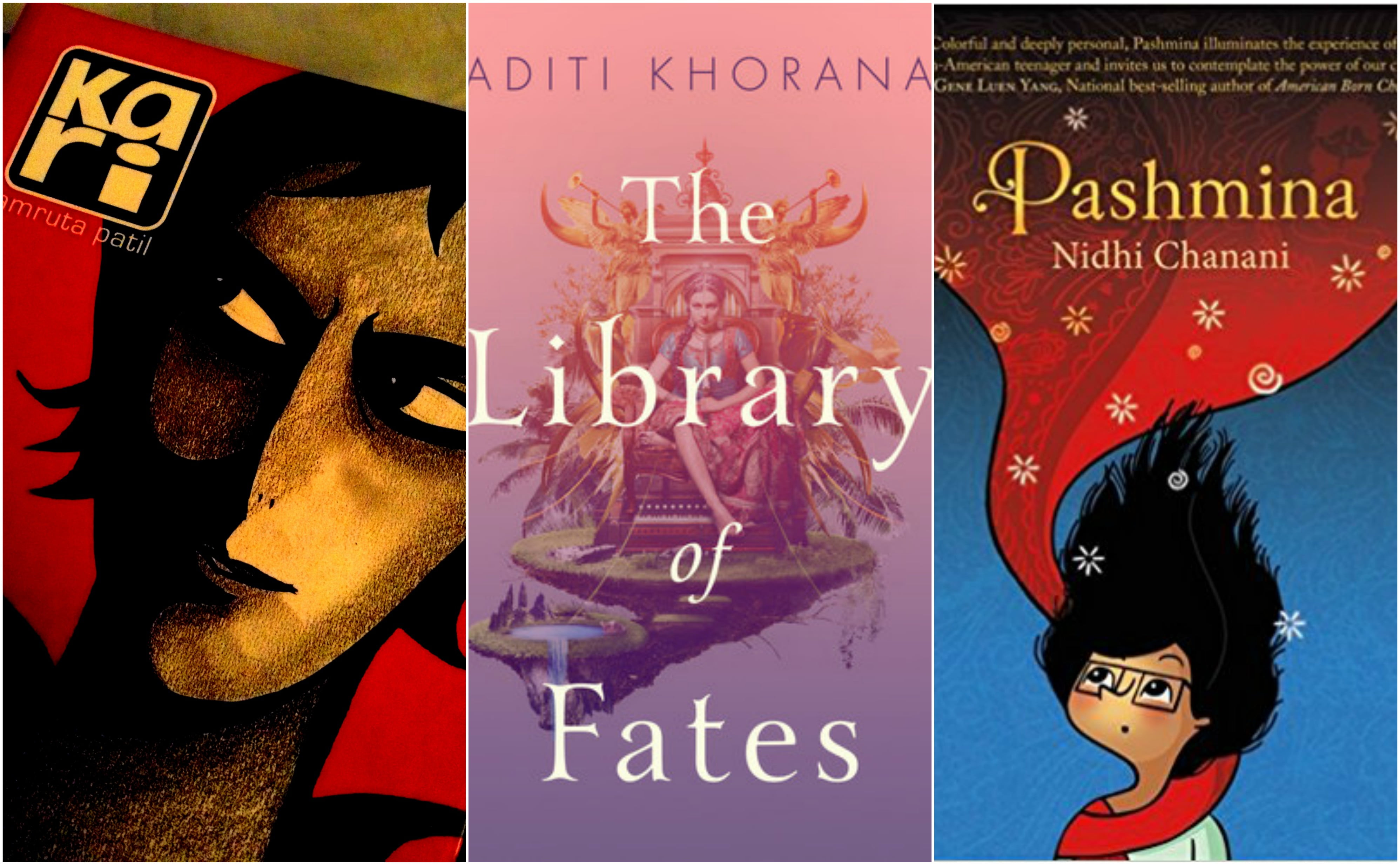

Mythology isn’t the only storytelling route, of course. Amruta Patil’s Kari and Nidhi Chanani’s Pashmina bring to readers a gritty graphic novel, while Mimi Mondal adds to essays and short story collections surrounding the genre of speculative fiction and sci-fi. Rahul Mehta’s No Other World is a diaspora story of an Indian-American gay boy in the 1980s and 90s, while Sandhya Menon’s When Dimple Met Rishi is a rom-com style diaspora story set in twenty-first century California.

Samit Basu’s GameWorld Trilogy and Saurabh Dashora’s Starship Samudram are immersed in a sci-fi setting, just as much as Aditi Khorana’s The Library of Fates is a plunge into fantasy. The young-adult genre is brimming with possibilities and potential for South Asian stories and voices – it’s only a matter of boosting the signal.

Also Read: 9 Young Adult Books With Diverse Leads That You Shouldn’t Miss

Featured Image Credit: Amruta Patil, Goodreads and Amazon

About the author(s)

Pallavi Varma grew up in Bangalore but spent a lot of her time living in the fantasy worlds she creates for her stories. She has a BA in English Honours from Christ University, an MA in Creative Writing from Cardiff University, along with being a professional binge-reader, kpop-enthusiast and Netflix-watcher.