The midnight knock on the door and the disappearance of a loved one into the hands of authorities is a 20th-century horror story familiar to many destined to “live in interesting times.” Yet, some stories remain untold. Such is the account of the internment of ethnic Chinese who had settled for many years in northern India. When the Sino-Indian Border War of 1962 broke out, over 2,000 Chinese-Indians were rounded up, placed in local jails, then transported over a thousand miles away to the Deoli internment camp in the Rajasthan Desert.

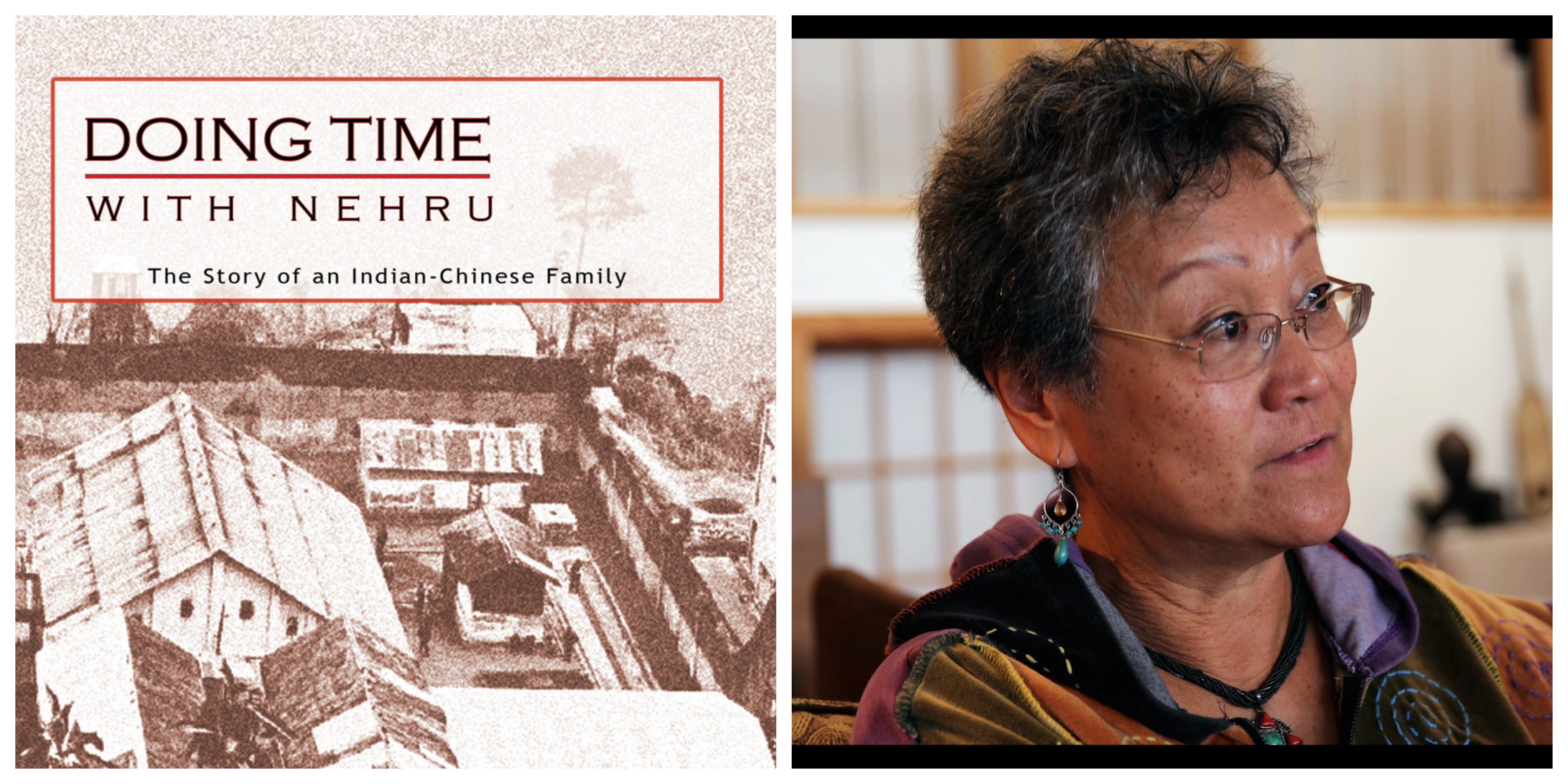

Born in Calcutta, India, in 1949, and raised in Darjeeling, Yin Marsh was just thirteen years old when first her father was arrested, and then she, her grandmother and her eight-year-old brother were all taken to the Darjeeling Jail, then sent to Deoli. Ironically, Nehru – India’s first Prime Minister and the one who had authorized the mass arrests – had once “done time” in Deoli during India’s war for independence. Yin and her family were assigned to the same bungalow where Nehru had also been unjustly held.

Eventually released, Yin emigrated to America with her mother, attended college, married and raised her own family, even as the emotional trauma remained buried. When her own college-age daughter began to ask questions and when a friend’s wedding would require a return to her homeland, Yin was finally ready to face what had happened to her family.

A day or two later, three Indian police officers showed up. They drove right up to Ajit Mansion in their military jeep. Since cars were not allowed into the Chowrasta area, the vehicle drew attention. We heard the commotion and peeked out the window. People crowded excitedly around the jeep to see why it was there. One officer remained with the jeep while the other two came up to our flat. They were in khaki uniforms and appeared unemotional. They told us they had come to take us away and that we should be prepared to be away for a long time. They didn’t take kindly to our questions and answered brusquely. They didn’t know where we were being taken or how long we would be gone. We needed to take warm clothes, bedding, a few pots and pans, and other essentials needed to exist for many months. We were allowed to take one bag each and then they told us they would be back in an hour.

The officers returned shortly after Mr. Lee arrived. They helped us carry our things down to the waiting jeep. By now there were a few dozen curious people surrounding the jeep. They watched as we got into the vehicle. I don’t know what they were thinking. I had the feeling they were in disbelief and wondering why we were being taken away. My parents had been in India for over twenty years and were a vital part of the community. They ran a successful and popular restaurant, were liked and respected. Both my brother and I were born in India. Weren’t we Indians? Why were we being treated differently? What had we done?

We said goodbye to Mr. Lee and thanked him for everything he had been able to do on our behalf. He looked forlorn standing there as we climbed into the jeep.

I looked at our neighbours who were watching us being carted off like common criminals: a grandmother with bound feet, her thirteen-year-old granddaughter and her eight- year-old grandson. They didn’t look at us as old friends and neighbours. It was a different look, one of astonishment. It also seemed to say we were outsiders. A flood of simultaneous emotions overwhelmed me: bewilderment, fear of the unknown, and a feeling of shame: shame for being Chinese.

Excerpted with permission from Doing Time With Nehru by Yin Marsh, Zubaan. You can buy the book here.

Also read: Book Review: Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora?

About the author(s)

Feminism In India is an award-winning digital intersectional feminist media organisation to learn, educate and develop a feminist sensibility and unravel the F-word among the youth in India.