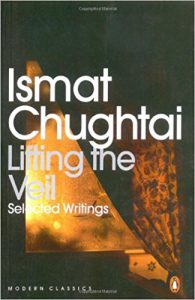

In the selected writings Lifting the Veil, Penguin Random House India’s Modern Classics brings together some of Ismat Chughtai’s popular (and then-controversial) short stories, a collection that is reminiscent of the times when the cultural mores and traditions reeked of conservative values limiting both social and personal freedoms, particularly for women.

Lifting the Veil by Ismat Chughtai

Courage, then was not a quality extraordinaire displayed in battlefields or in resistance against the imperium, but also an ordinary, everyday act much like that of Chughtai’s characters, performed often without celebration and with seminal consequences. Ismat Chughtai comes from a long line of women who have lived within patriarchal settings, often under a veil – conversing in hushed tones, walking on tiptoes, and behind closed doors – waiting for the right moment to come out. In Chughtai’s work, these women find their compatriots, and as her readers, we, our own.

The first story in the collection, Gainda, published in the year 1938, is among Chughtai’s earliest published works that in its quality of reflective narration, fragmented dialogue, and partial description builds a platform for discussions on caste, class, gender, and sexuality. Exploring the themes of caste and class oppression, female friendships, premarital sex and pregnancy, domestic violence, and romantic relationships and their disparate consequences within high societies, Gainda has a reverberation that is akin to the sound of truth. The young narrator has a distinct style of remembering events from her past, events that she has witnessed but has escaped from unscathed. One can imagine a gentle peek from Harper Lee’s very own Jean Louise Finch, as Chughtai’s narrator continues her dramatic recollection.

The story begins with, “This is OUR shack,” a proclamation made by the young narrator as Gainda as she smoothens the ground to begin their play-pretend. The act of claiming one’s own space, a feminist act, symbolises a breaking away from the society that confines not just physical bodies but also expression, exploration, and agency. In its own limited way then the secret meetings between Gainda and the narrator encourage a special bond beyond that of class and caste realities raising political consciousness among the girls even if they do not understand them yet.

Little is known about Gainda, the young narrator’s description is often limited to her perception of what is ‘important’. She describes her awe and desire to be like Gainda, becoming “the sole owner of a set of glittering silver jewellery…” and strutting “around showing off her finery“. Yet the disjointed pieces of information come together as if filling up a puzzle, revealing Gainda’s particular story within a long-surviving exploitative system.

Also read: A Feminist Reading Of Chauthi Ka Joda By Ismat Chughtai

Gainda is not the archetype of rebellion; she is but a shy, cheerful, knowledgeable girl who “was a treasure-trove of such [‘strange’] events“, acting her part as a young widow, and as an impressionable adolescent discovering her sexuality, interests, and desires. Chughtai’s treatment of Gainda in the story, however, elevates the young girl and her story to a status equal to those who have been documented to create history.

In addition, the roles accorded to multiple female characters such as Amma and Bahu, including the use of a second narrator of the same sex, redistributes literary space (“This is OUR shack“), to hold stories like that of Gainda’s. As the literary critic Edward W. Said writes in his Introduction to Culture & Imperialism (1994), “The power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging, is very important to culture and imperialism, and constitutes one of the main connections between them.” So is kyriarchy and the patriarchal spaces and narratives it allows.

Chughtai claims this space again when she gives only a marginal role to her male characters; although, even that cursory glance is enough to confirm their position, status, and power within the household. Yet their absence does not remove them entirely or consume the consequences resulting from their actions or inactions; much like a portentous cloud, they continue to direct the course of events resulting in a gendered distribution of labour, prize, and suffering.

The male members, as they take off to dominate the world outside the household, cause the womenfolk to clean the mess left behind, both literal and figurative. The women clean up the mess with such proficiency, hiding the ‘filth’ behind their own veils, such that men continue to exist and enjoy a privileged status. No wonder then that ‘lifting the veil’ is an uncomfortable act, at least for one-half of the society. Gainda is only one of those many uncomfortable acts.

Also read: 5 Ismat Chughtai Stories That Highlight Women’s Issues Pertinent Today

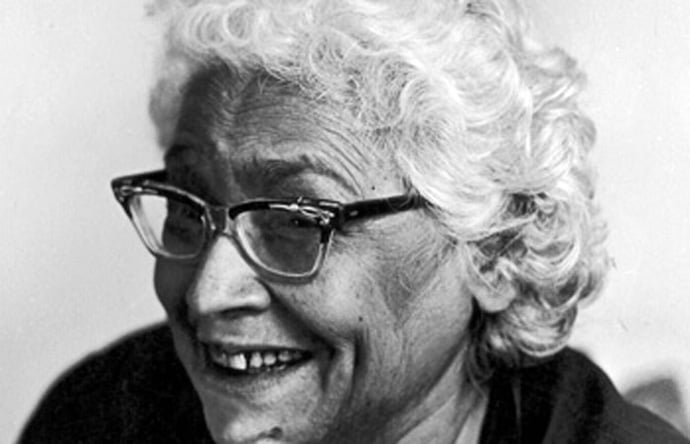

Featured Image Source: Wikipedia

About the author(s)

Rathi R teaches sociology and psychology at a media institute. When she is not teaching, she reads postcolonial and feminist literature and nonfiction writings. She has Master's degree in Social Work and is currently based in New Delhi. She writes at ratzest.wordpress.com.