Posted by Shalmi Barman

4 July, 2018. The Executive Council of Jadavpur University (JU) decides by nine votes to six to scrap B.A. entrance examinations for six Arts Faculty departments – English, Comparative Literature, Bengali, Philosophy, History, and International Relations – and instead admit students on the basis of board examination marks. The decision, which overturns university admission norms of 40 years, comes after weeks of negotiation in the Admission Committee and multiple compromises to the existing admission process offered by departments like English and Comparative Literature. The exams were due to be held barely a week later and preparations were already underway at the time of the announcement.

A growing crowd of students sits in at Aurobindo Bhavan, the main administrative building, protesting the EC’s decision; they will stay all night and the next day through heavy rain. The Vice-Chancellor claims that he has been confined to his room (though the entrance to the building is kept clear). “This is unfortunate and an undemocratic way of protesting,” he says to media outlets. “My question is what role do the existing students have in this issue?” It is a cynical question and a rhetorical one, because everyone who belongs to Jadavpur University knows what role its student body has in the entrance exams and the stake they hold in its transparent continuance.

9 May, 2016. The English M.A. entrance is on at JU. I am volunteering at Gate 4 as I have done every year as a student, checking ID and directing candidates. An ABVP rally had been announced on Facebook the previous evening; there are rumours of saffron processions approaching the university. Jadavpur Police have barricaded the stretch of Raja S. C. Mallick Road leading to the campus. Candidates and their companions keep trickling in; student volunteers keep an eye on the barricades and continue following instructions they are accustomed to through annual practice.

Come rain or political threats, the entrance tests at JU – complicated multi-stage processes involving the participation of faculty, staff, and students – must go on. The ones for the English department, which are the ones I am most familiar with, draw a few thousand applicants each year and are large-scale affairs spread over the entire campus. From invigilating the exams, to preparing classrooms and seating charts, to managing the inflow of parents and guardians and lost candidates alike, every bit of work is a community effort. Students past and present, under the guidance of teachers, are involved in them from beginning to end.

JU decided by nine votes to six to scrap B.A. entrance examinations and instead admit students on the basis of board examination marks.

Many alumni remember the JU entrance exams as a cherished initiation to college life, but they are meaningful beyond nostalgia. They test critical thinking abilities in a way school board exams, with their focus on objective-heavy rote learning, simply cannot. Question paper formats are revised frequently, and the topics are diverse, dynamic, and lie all over the cultural map. For many students fresh out of school, college entrance tests like the ones conducted at JU were the first indicator that serious study of the humanities requires more than the ability to memorise facts. Faculty members who correct answer scripts are adept at detecting creativity and intelligence that the very structure of mass standardised tests do not encourage or reward.

The entrance tests at JU are an exercise in democracy. They are a vital means to a quality college education for gifted candidates across class and educational backgrounds, and a vote of confidence in the independent functioning of academic departments.

Why, then, has the JU Executive Council, overruling the Admission Committee and a referral from the Advocate-General, cancelled B.A. entrance examinations wholesale? The EC claims it is a ‘one year only’ solution to a stalemate between parties with opposing views as to whether the setting of question papers and correction of answer scripts should be done by university faculty or outsourced to an external committee. But admission on the basis of board exam marks sets a dangerous precedent and violates the faith of the 17,000 candidates who have applied for B.A. admission to the Arts Faculty in 2018. Why did the question of altering an existing liberal system that no candidates had complaints against arise at all?

For many students fresh out of school, college entrance tests like JU’s were the first indicator that the study of humanities requires more than just rote memory.

The matter was first raised in the EC by a faculty member who is a known Trinamul spokesperson. Education Minister Partha Chatterjee has stated on record that JU “should not have two standards – that admission to some subjects will be on the basis of merit and other section will have merit and entrance exams.” Leaving aside the incredible implication that board examinations assess ‘merit’ while specialised entrance tests do not, it is worthwhile to note the Minister’s concern about standards. It seems almost redundant to point out that since the study of humanities require different skillsets than does science or engineering, candidates for these fields should be assessed through different methods. Why this governmental zeal to impose ‘one model’ on the admissions procedures of an autonomous state university?

Also Read: #InjusTISS: The TISS Student Struggle Against Cutting Financial Aid For SC, ST And OBC Students

It is no secret that political totalitarianism loves standardisation. The totalitarian invokes the ideal of fairness to promote uniformity. He appeals to notions of merit as he reduces intellectual potential to numbers. And so, by the logical reversal characteristic of totalitarianism, the entrance exams at JU are construed as unfair because they assess candidates without the use of algorithms or referral to third parties but through the consensus of its main stakeholders. It does not matter that this charge can and has been refuted – that each answer script is scrupulously checked, rechecked, and revised collectively by faculty members is widely known. It does not matter that the existing system has yielded consistent positive results – the record of academic excellence across faculties at JU is public knowledge.

The totalitarian does not care about fairness or merit. He only wishes to control. To control the class composition of JU’s arts departments is to control the character of the university itself. Academic research and the careers of aspiring humanities students are expendable in the context of this aim.

It is no secret that political totalitarianism loves standardisation.

Each year till now, I have advised English department hopefuls to not waste their money on guidebooks claiming to crack the JU entrance exam formula. There is no static formula – this is why the exam is so challenging and so liberating. At age 18 I had never enjoyed writing a test more than the JU B.A. entrance where I wrote an essay on literariness in detective fiction, a topic no board exam had prepared me for. Some of the batchmates and alumni I know to be stellar humanities scholars would laugh about coming to English after getting 50% in Higher Secondary or flunking out of JEE.

I wonder now if the future holds Aakash Institute equivalents for the humanities. I wonder what my alma mater will look like when I return after completing my PhD. As outrageous as the Trinamul government’s interference in the affairs of an autonomous university seems to those of us who have benefited from its freedoms, it feels like a foretaste of what is to come. I hope those who do not belong to JU and often view it with suspicion realise that this impacts not just one university but also every intelligent teenager who wants an affordable liberal arts education at one of the foremost institutions in this country. JU is a public asset and we the public are implicated in its fortunes.

Also Read: Let’s Talk About How DU Women’s Hostel Fees Are Sexist

Shalmi Barman graduated from Jadavpur University in 2016 with two degrees in English. She is now on her way to the University of Virginia intending to collect another.

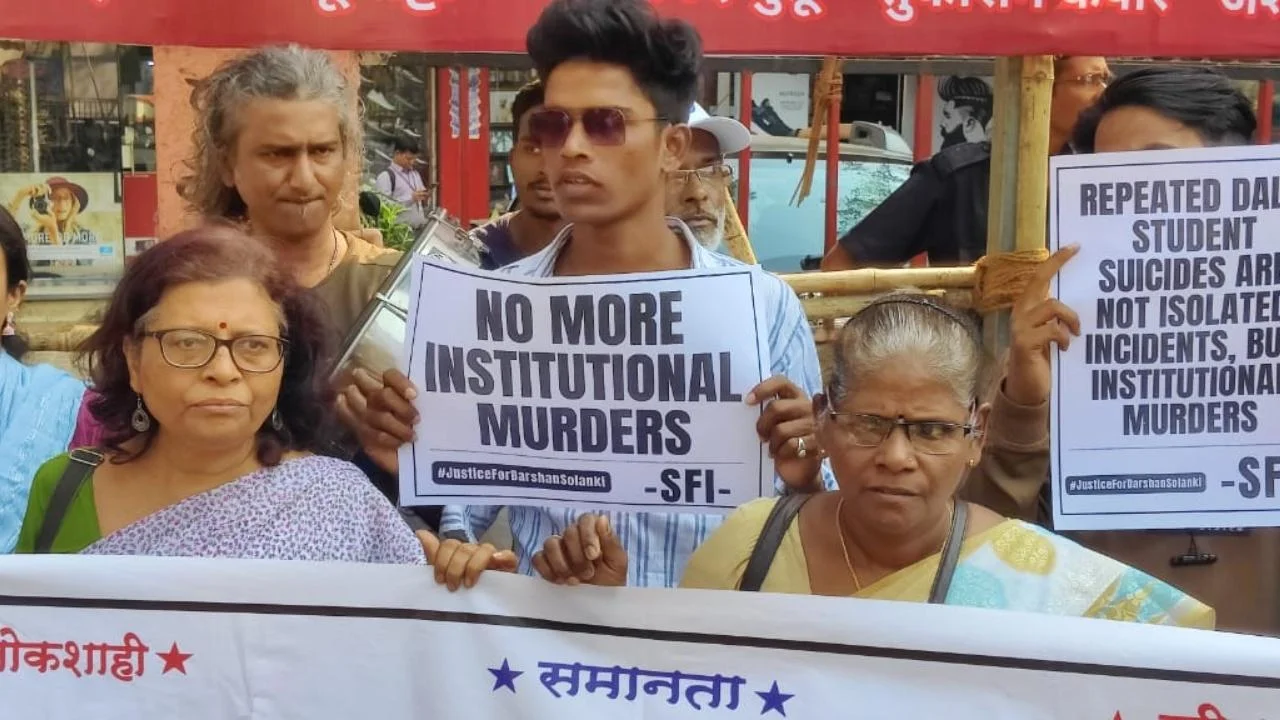

Featured Image Credit: Facebook/aisaju via India Today

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.