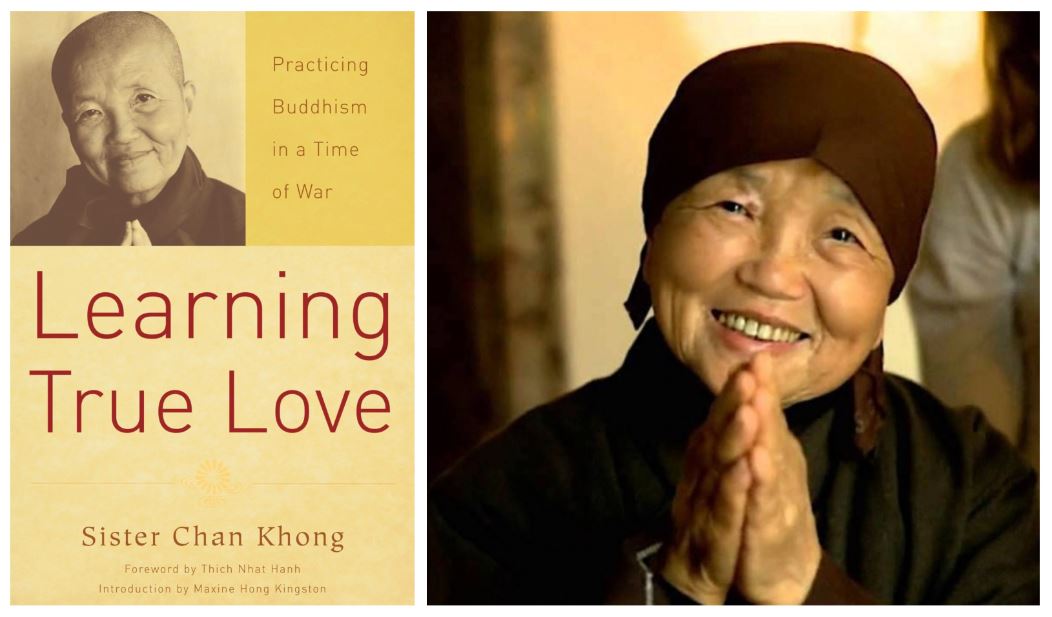

Learning True Love: Practicing Buddhism in a Time of War is a poignant tale narrating Sister Chan Khong’s journey through the Buddhist way of living. Born in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam, Sister Chan Khong was intimately acquainted with Buddhism early in life. Much of her life coincided with the Vietnam War in the 1960s. Under the imminent threat of displacement and death, the Buddhist fraternity in Vietnam navigated the nation, distributing aid and spreading the message of God. Sister Chan Khong’s autobiographical prose compels the reader to step into her shoes as she traverses the war-torn region – and Buddha’s teachings – to learn the true meaning of charity, spirituality, and love.

Given the title of Chan Khong, meaning ‘emptiness’, by her spiritual guide, Thay Thich Nhat Hanh, she attempts to live up to it by capturing as much knowledge as possible in her pristine and limitless heart. She also strives hard to overcome the obstacles within Buddhism against women joining the sangha. Buddhism discourages women from becoming nuns. Being perplexed by this exclusion, Sister Chan Khong questions Thay who also reiterates that according to the teachings of the Buddha, women cannot attain moksha because of their rootedness in the material world.

Also read: Book Review: Americanah By Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, The Politics Of Writing About Love

Disappointed but not disheartened by this information, she continued on her path of serving the destitute with a strengthened resolve. She used ingenious means to gather food for the poor, provide them with education and legal aid. Along the way, she met several people who shared her desire to bring peace to Vietnam. One of them – Sister Ma – self immolated herself in protest of the war. This act of hers created a landslide of support for Buddhist groups and their work. But Sister Chan Khong grapples with the moral implications of taking one’s life and whether selflessness can be expressed through it.

She never calls herself a nun, only a social worker, for she finds that religion is just an excuse for her to engage in such labour.

At no instance does Sister Chan Khong explicitly describe her disadvantaged position as a woman in a traditional Asian society. She doesn’t have explicit radical feminist ambitions. Instead there is an underlying desire to break free of the backward bonds that kept her away from education, her work, and her god. She never calls herself a nun, only a social worker, for she finds that religion is just an excuse for her to engage in such labour.

Learning True Love also delicately deals with the topic of marriage. Sister Chan Khong longingly reminisces the dreams of marriages and weddings that every young Vietnamese girl has. She thinks of a simpler time when achieving these mundane goals would have sufficed for her. But despite receiving a marriage proposal from a colleague, she declines and steadfastly trudges along the path of social work. On her suitor, Tran Tan Tram’s wedding day, Sister is weighted with the knowledge and acceptance that she would never get married. She embraces a life devoted to the people and says that she could not “take care of the wild children in the slums and remote areas who desperately needed help”, if she married.

The Vietnamese people’s lives were fraught with conflict and the pressure to align themselves with either the Communists under Ho Chi Minh or the Americans down in Saigon. Sister Chan Khong realises that this polarisation hindered her connection with the people and so vowed to stay neutral. Learning True Love , in all its understated glory, never ventures into the political arena and does not overtly propose alternatives to war. Instead, it offers a glimpse into the seemingly simple, yet Herculean task, of rehabilitation and instilling faith in the people again.

She is unable to own the book completely because her history and background have shaped the way women think.

The intertwining of two writing styles, prose and poetry, has created a story that is larger than life, while remaining rooted in temporal questions of a woman’s position in religion, philanthropy and nationalism. The poetry interspersed through the text is a window into the experiences of war that Sister and Thay were witness to. One such heart rending piece says,

A young father

whose wife and four children died

stares, day and night into empty space.

He sometimes laughs

a tear-choked laugh.

What makes the book truly unforgettable is the unique vantage point that Sister Chan Khong presents to the reader. She is not only a female citizen caught in the power struggle between two factions (led by male leaders) but is also a nun. Both these positions have been largely neglected in historical discourse on Vietnam. This double invisibilisation is not at the forefront of the plot but still leaves its aftertaste. Despite being an autobiographical writing, Learning True Love never comes across as self-consumed. It is almost as if Sister Chan Khong wishes to distance the narrative from herself and focus more on the nuances of a common person’s life and the Vietnamese identity.

Although Learning True Love is replete with instances of courage and strength that Sister Chan Khong undergoes herself, the very detachment of hers from the narrative can be critiqued. In the Asian context, individuality is subservient to the community. There is also a tendency to attribute success or pain to God. So when Sister Chan Khong invokes Avalokitesvara, a Bodhisattva, after surviving a painful period of time, she negates her own heroism and fortitude. Over the course of her time in violent situations, she never acknowledges her ability to overcome the pain despite being told that women cannot do so. She is unable to own the book completely because her history and background have shaped the way women think.

Also read: Understanding Buddhism Through A Feminist Lens

Nevertheless, Learning True Love is a commendable piece of writing that does not follow just a personal journey but also one of a community, a religion and a nation.

Featured Image Source: Goodreads

About the author(s)

Divya Godbole is a Sociology Honours student, interested in understanding how personal troubles turn into public issues. But she finds solace from these existential questions in K-pop, cats and Pride and Prejudice.