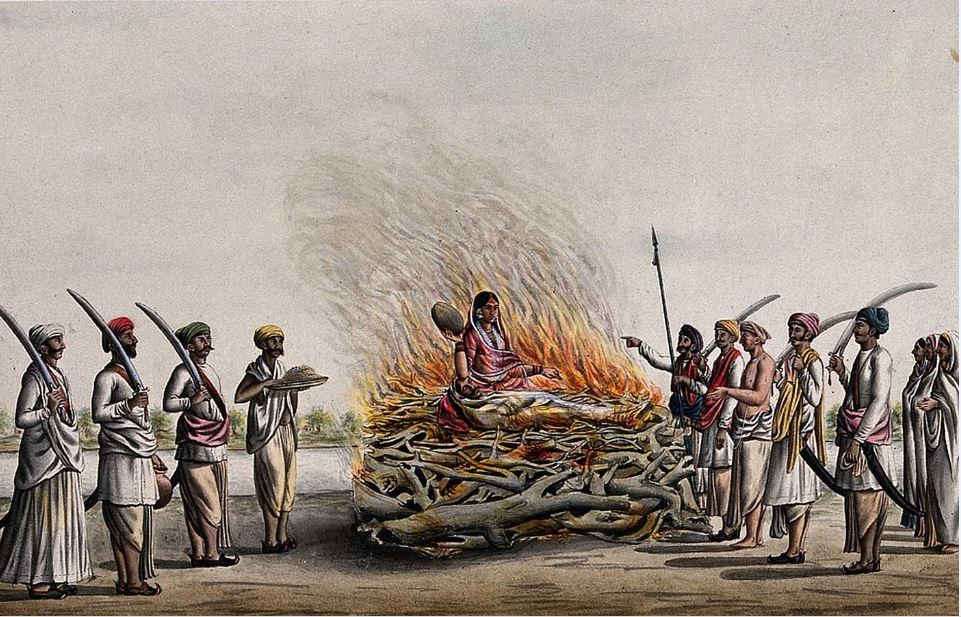

One of the landmark moments in the history of India was the abolition of the practice of Sati – the self-immolation of the widow on the funeral pyre of her husband. The abolition of Sati is one of the first things we are taught when learning about colonialism in India – about how Raja Rammohan Roy, a 19th century moderate leader from Bengal advocated against the cruel practice of the burning of the widow as a way to guarantee that both the widow and the deceased husband would reside in heaven.

Learning about this led us to believe that this was the beginning of the fight for women’s rights in India. It is no doubt that Sati was a cruel practice that needed to be abolished, but the way it had been done is something mainstream books have not told us correctly. Feminist historians over the years have created a separate body of knowledge that explains social phenomena in India from the perspective of how it affected women, Sati being one of them.

Initially a trading company, the British East India Company gradually made its way into the murky politics of the Indian subcontinent. With their ultimate aim being total control, the foothold they needed on Indian soil to achieve it was through the attack on ‘Indian culture’ for being barbaric, savage and in need of reform that involved imbibing Victorian morals.

the entire base of the British argument was on the assumption that the indigenous people strictly followed religious scripture as a way of life.

They took to social evils to maintain their argument, and Sati was the perfect entryway. While Sati as a practice existed in the subcontinent, it wasn’t as rampant as the British made out to be. Collection of data on the death of women in and around the Calcutta region between 1815 and 1828 was presented to make their case before it was finally abolished in 1829, but the process of collecting and analysing the data was where the loopholes existed.

The Official Discourse Around Sati

Sati had become a hot topic in colonial Bengal in the early 19th century. To prove that Sati was a barbaric practice, the British appointed Pandits in the civil courts and Nizamat Adalats (criminal courts) to help them build a case against it by decoding religious scriptures. The British posed specific questions regarding the practice and urged the Pandits to answer them by interpreting texts from scriptures like the Manusmriti and other Shrutis and Smritis.

Also read: Reading Caste In Holi: The Burning Of Holika, A Bahujan Woman

The British argued that Sati was not practised in order to send the husband and wife into heaven, but because widows, entitled to some of the family property after their husband’s death (through the Dayabhaga Law in Bengal), became a liability due to the fear that they might claim it. Thus, coercing them into the funeral pyre was a safe bet.

This process is interesting for several reasons. Firstly, the entire base of the British argument was on the assumption that the indigenous people strictly followed religious scripture as a way of life. Secondly, in the vyavashthas made by Pandits for decoded texts, sentences would often be, “…the author must have had in contemplation those who declined to do so”, or, “From the above quoted passages of the Mitateshura it would appear that this was an act fit for all women to perform.” These interpretations made by Pandits were taken to be unequivocal and absolute, even though they were visibly just interpretations.

The vyavasthas also elaborated on how practices differed in towns, districts, and among castes, but those were largely ignored – they were regarded as peripheral aspects of the ‘main’ act of Sati. The problem lies in the fact that the British wanted to prove that indigenous people followed religious practices with no conscience and they modified the interpretations to suit their goal, despite having proof that it may be otherwise. This assumption became the official discourse on Sati.

Modification In The Practice Of Sati, 1813

While the aim of the British was to prove that religion was the basis of the existence of the people of the Indian subcontinent, they wanted to do so without directly infringing upon their sentiments. In 1813, the law that allowed Sati was modified, according to which there was now a legal Sati and an illegal Sati – the former meaning that the widow consented to it and the latter meaning that she was coerced into it. Two things come out of this arrangement – one, that the British did not target Sati because it was a practice cruel to women, but to argue that it was the men who were barbaric, and two, that volition or consent are invalid here because there was no way to tell if the widow had consented or was forced to consent.

The problem lies in the fact that the British wanted to prove that indigenous people followed religious practices with no conscience.

In 1815, when systematic data collection on Sati began, officials were instructed to witness each and every detail of the act from start to finish – the widow’s body language, what she was told, and the behaviour of those around her. Not only is it difficult to record consent when it is heavily contextual in the case of women who have no power or status in a patriarchal society, but it is also ridiculous to think that consenting women would validate the practice of Sati.

Raja Rammohan Roy And The Hindu Conservatives

Raja Rammohan Roy is known as the pioneer of women’s rights in India, specifically because he came out in support of the abolition of Sati. Since 1818, Roy wrote in great detail about Sati and how he was pro-abolition. His writing, however, also focused on reading and interpretation of scriptures. Roy argued that Hindu scriptures did not condone or encourage Sati, and his views resonated with the British argument that widows were coerced into the pyre for material gains.

Roy was aware of the patriarchal context behind consent in the case of women committing Sati, but that remained in the margins of the colonial debate. In his works, he defended the religious scriptures and asserted that widowhood was glorious – a life of asceticism was the way for widows to live. Just like the court-appointed Pandits, Roy made his case with the help of the shastras such as Manusmriti, Shrutis and Smritis, also declaring which scripture is more sacred than the other.

Manusmriti, according to him, was above all because it did not mention Sati anywhere. In 1830, he presented a petition along with 300 signatories to the then Governor-General of Bengal, Sir William Bentinck with more evidence against the wrongful interpretation of the scriptures – a year after the enactment of the Sati Regulation Act.

The Hindu conservatives had a different, straightforward point of view – they were against the abolition of Sati because it was a part of their customs. They argued that Sati was a practice that would give the husband and his wife immediate spiritual bliss. Ascetic widowhood, on the other hand, was suffering.

According to their interpretations, ascetic widowhood was an option in case the widow cannot perform Sati. It is interesting to note that the conservatives mentioned ‘customs’ as an argument, which was contrary to the impression the British had of them – their assumption of the indigenous people blindly following scripture without improvisation fell flat. But that didn’t make a difference because the conversation ultimately steered to scriptural interpretations. The orthodox differed in opinion against Roy on the basis of which shastra was more sacred. When questioned about why Sati was not mentioned, the conservatives fell back on the ‘custom’ argument – events like Durga Puja were also not mentioned in the text, but not performing it would be considered sinful.

In the petition they created to present to the Governor-General (with 800 signatories), they stated that there was a printing mistake in the Manusmriti that was distributed across Bengal. The Hindu conservatives were of the opinion that the ‘liberals’ opposing Sati were non-believers of religion and that because they had the monopoly on the knowledge regarding Hindu culture, their views had more weight. For the conservatives, the narrative boiled down to believers versus non-believers.

In his works, Roy defended the religious scriptures and asserted that widowhood was glorious.

Each side had its own ways of interpreting texts, but neither of the parties was concerned about how Sati affected women.

The Women’s Question

It has been established that no party involved in the Sati discourse had women’s inferior status in mind. All three parties used Sati to establish the authenticity of their culture. The British wanted to bring Victorian modernity to the Indian subcontinent while the elites and conservatives used scripture to assert the ‘golden culture’ of the subcontinent had merely gone astray – it was still alive and well.

The women in this discourse by men were reduced to a dichotomy of superheroes and slaves, all depending on whether they walked into the pyre by consent or coercion. Even Roy, who understood the social inequalities behind Sati, glorified women going into the pyre by calling them heroes. There were recorded cases of women resisting the coercion, but that was not seen as a product of the fundamental problem with scriptures and customs, but as the inability of the men who were forcing this culture on them. Any sign of women’s agency was invisibilised.

Between 1815 and 1828, a total of 8,134 cases of Sati were recorded, mainly among (but not limited to) upper caste Hindus. The data had its loopholes – the figures included deaths of women that had nothing to do with Sati; some died of sickness. A good percentage of women were above 40 years of age when they performed the act, contradicting the notion that widowhood was unacceptable.

The fact remains that women were on the receiving end of these practices, but they were never central to these arguments. Women’s bodies were the ground on which the war of authenticity was fought among the British and the elites. The Sati Regulation Act did get passed in 1829, but in the grander scheme of things, none of it was for the benefit of women.

Also read: Whose Stories Are Told In Indian History?

The colonisation of the Indian subcontinent for 200 years was a series of cunning moves made by the British to not only loot the subcontinent of its material wealth, but also the transform their society to make it more Victorian. The argument of Indian culture as barbaric became the basis of changes in the following centuries, transforming the political, social and economic structures of the subcontinent. The women’s question remained central to the war between the Indian nationalists and the British and they continued to be markers of ‘Indian’ culture – something that can never be homogeneous.

References

- Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India by Lata Mani

- Historical Narratives

- Dead Women Tell No Tales: Issues of Female Subjectivity, Subaltern Agency and Tradition in Colonial and Post-Colonial Writings of Widow Immolation in India by Ania Loomba.

About the author(s)

Kanksha Raina is a journalist based in Mumbai, Maharashtra. With a Master's degree in Gender, Culture & Development Studies, Kanksha is passionate about pop culture, cinema, and sexuality, with a particular focus on women's experiences. In her spare time, you can catch her reading, binge-watching her favourite TV show for the 10th time, or spending time with her cat. She is an alumnus of the Asian College of Journalism.

Hi Kanksha Raina ji,

I came across you article when I was searching about Sati. In the whole article you main focus was on criticizing the British East India Company and their selfish gain, and introduction of the law against sati was their way of introduction of Victorian India.

And your strong argument was it was a tradition, which the ruling English has pointed and taken it out.

Your writing is single sided one, you were not interested in Feminist views, but just criticizing the rule of the day. Please do more research while writing these articles. Two places you quotes saying that they had given wrong data about the number of sati. But my question is should any woman should die like this? in the name of tradition. Should we have Sati back again? Was it good to get Sati Abolished or We should still have it?

The British have taken much wealth from India, I agree with it. But if you see the History of India and the Invasions and rules, They were a bit people oriented and did many notable things too.

Thanks for summing up the scenario so well. Curious to know who the ‘hindu’ undersignees were on the petition against abolition of Sati. Please do share if you have the information..

Every religion in every country has its evils, India is no different.

Sati was a barbaric religious act of murder borne from the insecurity of Indian men meant to control and possess women, nothing else.

Creepy, insane hyper-religious folk attempt to use the British as a scapegoat and attempt to blame them instead of their own religion.

It is sad that our people are attempting to revise their own history to make themselves look good and blame everything bad on foreign people and pretend their own religion and people don’t share fault in maintaining despicable, primitive practices ending in literal murder.

Wait a minute… How is holika a bahujan? Where is the proof she is a bahujan? She was the sister of a king. That makes her a kshetriya, right?

thanks a lot ! this helped me a lot to complete my project

BUT HOW DID HOLIKA BECAME A BAHUJAN as she was a SiSter of the KING