In a school in Bhopal mentioned in her research, Nazia Erum’s findings were quite interesting – the curriculum offered students a choice between learning Sanskrit and Urdu as a third language, owing to the sizeable Muslim population in the city. The students would shuffle class only during their third language lectures; they would come back to their mixed class when the lecture ended. While the students were given full freedom to choose, a pattern emerged: a majority of Muslim students ended up picking Urdu and a majority of the Hindu students picked Sanskrit.

Because of this, the school changed the seating pattern – all children picking Urdu would be put in one class, and children picking Sanskrit in another. The segregation had been made along linguistic lines, but stereotypes soon made their way – the Urdu section was looked down upon for being difficult and intellectually weaker than the Sanskrit section. While it cannot be proven explicitly, all the ‘star’ teachers had been assigned to the Sanskrit section owing to this subtle discrimination. The divide was now along religious lines and not just linguistic ones.

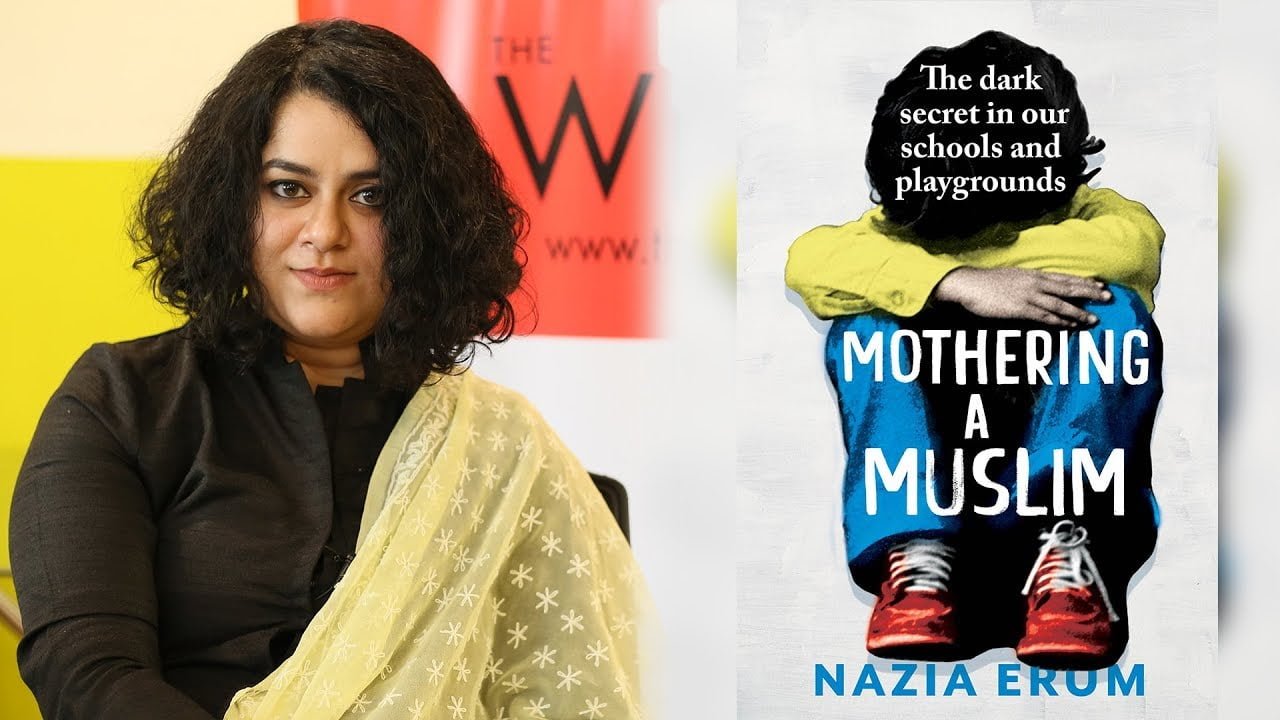

This is just one glaring example among the many subtle and not-so-subtle ways Islamophobia has developed in schools and colleges, and Nazia Erum delves into the meanings behind them in her book, Mothering a Muslim. The book is direct in its approach – it is a book about Muslim motherhood in the times of communal unrest. Erum analyses the possibilities and limitations of raising Muslim children by interviewing 145 families across 12 cities over the span of a year, and the insights are telling.

the term ‘Muslim woman’ is neither a stable nor singular category as we have been fed by the media.

Erum interviewed several Muslim women that came from differing backgrounds – a hijabi principal, a gynaecologist in a niqab, a district level swimmer, and a civil rights advocate just to name a few. Two major themes emerge from this book. First, that our search for Islamophobia must go beyond the violent events that we see – they are present in the most benign, everyday practices we take part in, and second, that the term ‘Muslim woman’ is neither a stable nor singular category as we have been fed by the media.

Erum’s book focuses on unpacking the Islamophobia rampant in the schools and playgrounds of the ‘good’, ‘elite’ schools and residences around the country. Her focus on middle and upper-middle class Muslim families in her work shows that there is a grave misunderstanding among well-off Indian families with regard to the violence that is perpetrated against the Muslims – the idea of violence and hatred against the Muslims occurring only among socio-economically backward populations is a myth.

Also read: ‘Ghoul’ Review: A Mirror To The Future Of India

Several women interviewed by Erum remembered instances of their children questioning their identity based on something they were told by other children in school and their playgrounds, all at a young age. Some children/teens were called ‘Pakistani’; some were cornered (out of ‘concern’) and asked, by their own friends, whether they supported ISIS or the Al-Qaeda; some were targeted with “Don’t mess with him, he will bomb your house”, and some were simply not invited to birthdays because some ‘concerned’ parents did not want their children to hang out with ‘those people’.

the idea of violence and hatred against the Muslims occurring only among socioeconomically backward populations is a myth

The girls, particularly, faced misogyny mixed with Islamophobia – one girl remembered being asked whether her father allowed her to wear short skirts and expose her legs, which ‘aren’t so shapely to begin with.’ Other instances include children telling their Muslim friends that they aren’t allowed to eat from their tiffins because their parents are apprehensive that they have beef. The mothers interviewed said that these kind of statements were a recent development; the kind of violence being perpetrated against the Muslims by far-right politicians since the 2014 elections has begun percolating within homes more explicitly, and the hatred has now become more apparent and unapologetic.

Erum argues that Islamophobia runs deep even among the most educated of the lot, and that needs to be addressed urgently because the same children using benign statements to remind Muslim children of their identity will grow up and pass on their bigotry to more people around them, or worse, vote for the people who encourage and condone that bigotry. The stories of children making communally charged statements speak heavily not only of the political environment we are in, but also of the kind of conversations children are being exposed to by their families and teachers.

Media channels that fuel this hatred are everywhere; no one is unaware of the kind of language and tonality used during political ‘debates’ on popular news channels. These shows are on during dinners, these things are discussed loudly in living rooms, and they are percolating into spaces where they shouldn’t be. Children are being exposed to blind bigotry that they don’t even understand; teachers and parents are not doing any better to teach them against it.

Also read: 8 Books That Capture The Essence of Muslim Women

A lot of schools were contacted as part of Erum’s research, and none apart from one did much about the complaints made to them by Muslim parents regarding hate speech against their children. Erum’s interviews show us that violence and ‘othering’ is not something that happens out of the blue – it is bred, encouraged and perpetuated through small, everyday activities that seem innocent and harmless.

Islamophobia runs deep and this fear translates into ‘self-censorship’, Erum elucidates. One woman said that she has warned her child about not making jokes at the airport. Another woman forbade her child from playing video games that involved shooting because she overheard his friend telling him that he shoots well. Some parents have discouraged their children from wearing skull caps outside for too long, and from playing in kurtas. These benign decisions have not appeared out of thin air; they are a product of the bigotry that has forced Muslims to change in order to fit in. Their identity thus is not theirs to own, but of the structurally powerful to modify.

While fundamentalism exists in Hindutva just as well Muslim fundamentalism is seen as the rule and not the exception.

The radicalisation of youngsters (and even adults in some cases) continues to be a matter of fear, and steps are constantly taken to ensure that impressionable people aren’t pulled into religious fundamentalism. While fundamentalism exists in Hindutva just as well (the Bajrang Dal, the Vishva Hindu Parishad, the Sanatan Sanstha), Muslim fundamentalism is seen as the rule and not the exception, which makes it difficult for the moderate Muslims to live without the fear of coming across as too devout, too Muslim.

Erum’s work also brings out an interesting thing about religion – the forwardness or backwardness of it is judged on the basis of the women who follow it. The stereotypes associated with Muslim women are quite rigid – the perpetual victim to ‘conservative’ religious laws and practices; always oppressed. While the truth is far from this, Muslim women often find themselves in a cold war with each other about who is a ‘good’ Muslim, often judged by the way they practice Islam.

Several women in the interview mentioned that they have received taunts and looks for not wearing the hijab or for celebrating their children’s’ birthdays, which they feel is counter-productive in an environment that already victimises them. There seems to be no winning for Muslim women – not wearing a hijab or a niqab implies that they are trying to fight the ‘rigidity’ of Islam, and choosing to wear one implies that they are stuck in the cycle of oppression. Erum challenges these stereotypes by stating that there is no one authentic Muslim woman who exists, and it is essential to see them as women who have the agency to make their own life choices without it being representative of their religion.

Also read: Universal Human Rights: The Interplay of Culture and Women’s Rights

Erum’s book is a great read for someone trying to understand the complex nature of the concept of ‘identity’ in a heterogeneous nation. I will conclude by stating something she said about the Muslim identity in India: “You cannot run from it. You cannot hide from it. You cannot embrace it.”

Featured Image Source: The Wire

About the author(s)

Kanksha Raina is a journalist based in Mumbai, Maharashtra. With a Master's degree in Gender, Culture & Development Studies, Kanksha is passionate about pop culture, cinema, and sexuality, with a particular focus on women's experiences. In her spare time, you can catch her reading, binge-watching her favourite TV show for the 10th time, or spending time with her cat. She is an alumnus of the Asian College of Journalism.