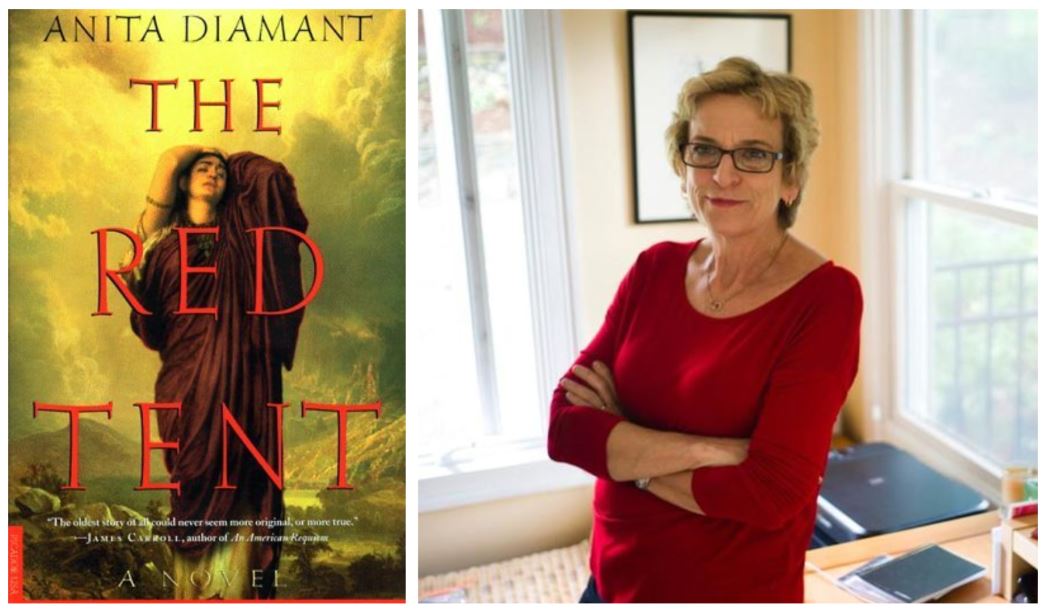

I discovered The Red Tent by Anita Diamant 21 years after it was first published. Yet it seems ageless and as relevant as it was nearly two decades ago, which, while it testifies to the joys of this work, is also a sad comment on the state of women in our society.

The Red Tent is a reimagining of the story of Dinah, the only daughter of Jacob, the man who, according to the Bible wrestled an angel and won the name ‘Israel’ and whose 12 sons became the 12 tribes of Israel. According to the biblical account, Dinah was raped by Shechem, son of Hamor the Hivite.

The book also says Shechem’s “soul was drawn to Dinah” and he wanted to marry her. Her father and brothers pretended to agree to the proposal and asked only that the Hivites be circumcised. The Hivites agreed and as they lay sore from the procedure, two of Dinah’s brothers, Simon and Levi, killed all the men. Then the other sons ransacked the city and took “All their wealth, all their little ones and their wives, all that was in the houses, they captured and made their prey.” This is all we hear of Dinah, who is taken “out of Shechem’s house” by her brothers.

The Red Tent is a bold, rich, and brilliantly written fill-in-the-blanks exercise undertaken by a modern Jewish woman reading the Bible. Rachel was the prettier of the two sisters and the woman Jacob wanted to marry but her father tricked Jacob into first marrying Leah, before letting him marry Rachel as well, according to the Bible. But if Jacob preferred Rachel, how come Leah had six sons and a daughter with him?

Diamant attempts to answer these and similar questions by imagining a world of women, where the men fade into the background. The red tent to which women retire when they menstruate or are ill or for childbirth takes centre stage in this re-imagining. And it is in the words and memories of the women that the story unfolds.

Also read: How The Iliad And The Mahabharata Have Depicted Women As Catalysts Of War

In Diamant’s world, the competition between the sisters Leah and Rachel fades into the background. The daily ritual of baking, cooking, cleaning, spinning, weaving are interrupted by time in the red tent, where the women bond and sing and celebrate the joys of life and mourn its sorrows, together. Although the Bible seems to suggest that menstruating women are unclean, The Red Tent celebrates both the onset of puberty (with a ritual that is nearly orgasmic) and menstruation.

The women retire to the red tent and are taken care of and indulged as they rest from their routine. Menstruating women almost seem to be indulging in the ancient Mesopotamian equivalent of a spa day! Contrast this with the period shaming still meted out in our country and it’s easy to see why the depiction of the red tent might inspire wistfulness.

And whether they have borne children or not, the women, by an unbroken association with women who have gone before them are all mothers, nurturing the ones who come after them, caring for the ones who can no longer take care of themselves. It’s a community, a world unto itself, a nurturing world, where knowledge and experience are shared as is pain and suffering. And this knowledge includes an unabashed discussion of the mechanics of sex and truthful acknowledgements of desires, with Dinah’s mothers acknowledging how they feel about Jacob and sharing the details of their wedding nights.

The red tent is the domicile for the mysteries of this world and the women who occupy it are its guardians and secret keepers. Compare this to our reluctance to have healthy and necessary sex education in classrooms since it does not align with our interpretation of our culture,which might at one time have been just as honest, ribald and joyful about the idea of sex!

By having her women (Rachel, Inna, Dinah, Meryt, Shif-re Kiya) become midwives, Diamant also draws a graphic and visceral picture of childbirth and its many complications. We are taken into the red tent where there is blood and placenta and the realisation that childbirth means a woman’s body becomes “a battlefield, a sacrifice, a test” where “death stands in the corner, ready to play his part.” And after it is over, Dinah “Like every mother since the first mother [is] overcome and bereft, exalted and ravaged. I had crossed over from girlhood. I beheld myself as an infant in my mother’s arms, and caught a glimpse of my own death. I wept without knowing whether I rejoiced or mourned.”

Women’s work is consciously recognised and highlighted in The Red Tent. While the Bible only mentions that under Jacob, Laban’s wealth grew, thanks to the Lord’s blessing, Diamant’s Dinah points out “The family’s good fortune and increasing wealth were not entirely the result of Jacob’s skill, nor could it all be attributed to the will of the gods. My mothers’ labors accounted for much of it. While sheep and goats are a sign of wealth, their full value is realised only in the husbandry of women. Leah’s cheeses never soured, and when the rust attacked wheat or millet, she saw to it that the afflicted stems were picked clean to protect the rest of the crop. Zilpah and Bilhah wove the wool from Jacob’s growing flocks into patterns of black, white, and saffron that lured traders and brought new wealth.”

The Bible lists the birth of Jacob’s sons with his wives, Leah and Rachel, and their maids, Bilhah and Zilpah, explaining the reason for the names. For example: “Leah conceived and bore a son, and she named him Reuben; for she said, ‘Because the LORD has looked on my affliction; surely now my husband will love me’.” The birth of a daughter though does not merit as much attention and we are offered no explanation for her naming: “Afterwards she bore a daughter, and named her Dinah.” As Diamant’s Dinah notes, she “became a footnote… a brief detour between the well-known history of my father, Jacob, and the celebrated chronicle of Joseph, my brother”.

The book is an attempt to claim her own space. For instance, in The Red Tent, Dinah’s four mothers toss names back and forth and then Leah whispers the name into the infant’s ear, almost as if she has a say in her name – Dinah. In this and other ways, Diamant gives women power over their lives, although it is not without consequences, she tells us.

While the biblical portrayal implies Dinah was raped by Shechem, Diamant imagines a girl who exercises her right to love and to have sex with the man of her choice. Her brothers, portrayed as greedy and jealous, go back on an arrangement that Shechem and his father had with their father and treacherously kill Shechem and all the men in his community. They then drag their sister, who is practically drowning in her lover’s blood, out of bed, tie and gag her and drag her home. Their justification – their sister had been dishonored, a justification that is still being offered by some families unhappy with their women and girls exercising their freedom of choice.

Traumatised by her family’s betrayal, Diamant’s Dinah leaves home after raining down some impressive curses on her family, especially the men, whom she sees as tacitly if not overtly complicit in the crime. What is amazing about Diamant’s narrative is that after giving birth to her son in a foreign land and being reduced almost to a wet nurse, Dinah finds herself with the help and support of female friends, and at the age of 40, finds love and passion again. A definitive wrenching back of agency by Dinah, who is so marginalised by the Bible that she is forgotten after her brothers exact revenge for her ‘rape’.

Diamant does not just recast her women with more power and resilience and stronger bonds and greater agency, she makes us question the status accorded to the men, chiefly Jacob and Joseph, exalted characters in the Bible. Jacob, for instance, is shown as changing his name to Israel to try and avoid being associated with the butchery of Shechem. It’s a fall from great height for a character said to have been given the name by the angel he wrestled with!

Everyone remembers the great miracle of Abraham’s god testing his faith and then, when Abraham was ready to sacrifice his only son Issac, providing a ram for sacrifice. Diamant has a lowly maid, Zilpah, point out that this is a cruel god and the incident was not without its consequences since Issac has been left with a stutter for life!

Diamant has acknowledged the influence of Virginia Woolf, who in A Room of One’s Own imagined a sister for Shakespeare, asserting the identity of the women who disappear from the male narrator’s history. Diamant’s Dinah is the narrator of The Red Tent and she tells her story because she is unwilling to be remembered merely as a ‘victim’ whose ‘honor was avenged’ in bloody fashion.

Her story is for female ears, just as she was, as the only daughter of her father and his four wives, the receptacle of all the stories of her mothers: “And now you come to me—women with hands and feet as soft as a queen’s, with more cooking pots than you need, so safe in childbed and so free with your tongues. You come hungry for the story that was lost. You crave words to fill the great silence that swallowed me, and my mothers, and my grandmothers before them. I wish I had more to tell of my grandmothers. It is terrible how much has been forgotten, which is why, I suppose, remembering seems a holy thing.”

Also read: 4 Feminist Authors Who Subverted The Fairytale Narrative

At the very beginning of The Red Tent, Dinah says, “We have been lost to each other for so long. My name means nothing to you. My memory is dust. This is not your fault, or mine. The chain connecting mother to daughter was broken and the word passed to the keeping of men, who had no way of knowing. That is why I became a footnote…” In bringing to light the stories of the women whom history seems to have relegated to the background (like the women who helped draft our constitution), we thus perform a holy task, strengthening the links that anchor us to the women who went before us and the women who will come after us. May we always keep telling the tales of the ones at the margins whom history conveniently forgot.

A bit of trivia: Interestingly, The Red Tent and a subsequent TV series based on the books led to red tent meetings, an opportunity for women to gather and draw strength from one another. And in the aftermath of MeToo, such a gathering of women seems to have evolved as an organic healing process for many here in India too.

About the author(s)

Raji makes her living editing copy. She is sorting her thoughts and trying to be a little less ignorant each day.