“Mother always has a mother. And Great Mothers are recalled as the goddesses of all waters, the sources of diseases and of healing, the protectresses of women and of childbearing, to listen carefully is to preserve. But to preserve is to burn, for understanding means creating.”

Trinh T. Minh- ha, Woman, Native, Other.

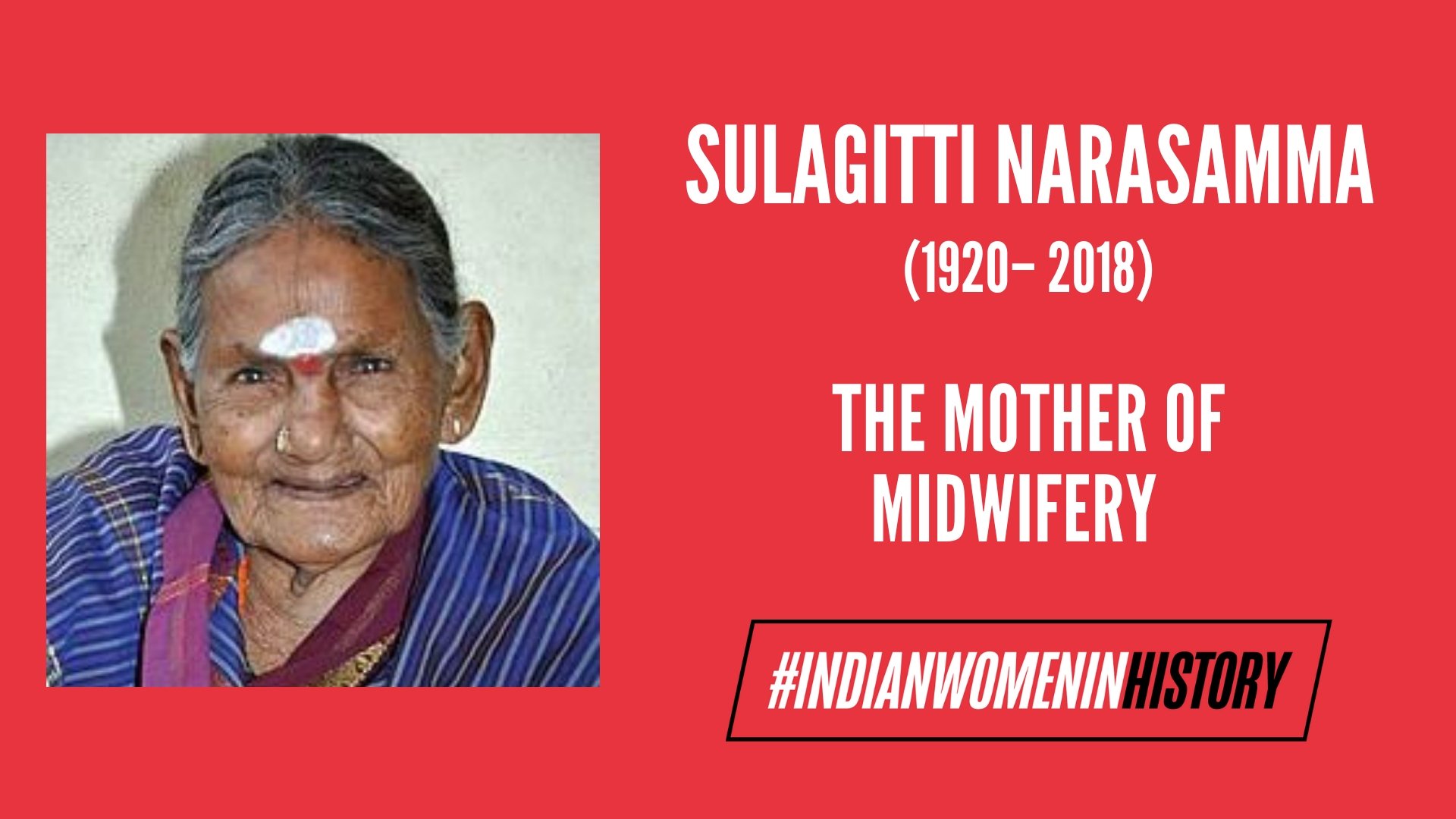

Sulagitti Narasamma, someone who can be claimed as the Mother of all, was an Indian midwife who won the Padma Shri in 2018. She delivered more than 15,000 babies for seven decades, without ever asking for a single cent. She is referred to as “Sulagitti”, a Kannada term which translates to “delivery work”, because of this. Narasamma helped deliver a baby at the age of 20 and since then she had performed traditional deliveries in order to serve the deprived regions of Karnataka that lacked medical amenities.

She was born in Krishnapura, Pavagada village in Tumkur district and belonged to the nomadic culture. Although illiterate, she embodied the vision of continuous and ceaseless learning throughout her life. She learned the art of delivering babies traditionally from her grandmother, Marigemma, who herself helped deliver five of Narasamma’s children.

She was fascinated by the ability she acquired – of being a protectress of women.

She was fascinated by the ability she acquired – of being a protectress of women. Moreover, she sought more opportunities to hone her skills and inculcate abilities to preserve life, so she listened carefully to the nomadic tribes that took shelter in her village. Through them, she learnt how to prepare natural medicines for pregnant women. She had a special talent of checking the pulse of a fetus, its health and the position of its head. In her acts of preservation, she has taught 180 students, including her daughter Jayamma, who is now a successful midwife herself.

Also read: Abala Bose: The Peerless Helpmate| #IndianWomenInHistory

She got married at the young age of 12, biologically mothered 12 children and 36 grandchildren and great-grandchildren till she passed away very recently at the age of 98, due to lung problems after being hospitalised for four months.

Midwifery

Midwifery was Narasamma’s forte and passion. The practice in itself is important to understand how women reclaim agency over their reproductive well-being after ‘intellectualism’ tried to displace it from them. The reproductive bodies of women have been landscaped and co-opted by the patriarchal structures of power to limit their resistance. Women, especially from the nomadic cultures and places inconspicuous to the medical community, have been collectively traumatised since colonisation.

The socio-political and economic forces have resulted in the denial of reproductive justice to women of certain marginalized communities. Through midwifery, women reconstruct their traditional systems and claim ownership of what happens to their bodies and health.

Not only does Narasamma’s ability to conduct all the deliveries in her village, before hospitals were made, a radical part of women reclaiming their reproductive health, but it also helps her connect to her nomadic roots and systems.

Nicolas Gonzales in her essay, Intersections voices an important aspect of midwifery, “[it] supports healing through creating environments where women can connect with their ancestral knowledge around their bodies while supporting them through their reproductive revolution of self-determination”. That is to say, not only does Narasamma’s ability to conduct all the deliveries in her village, before hospitals were made, a radical part of women reclaiming their reproductive health, but it also helps her connect to her nomadic roots and systems. Sulagitti Narasamma, fortunately, worked 70 years selflessly to re-construct the narratives of reproduction, sexual health and, motherhood.

Also read: Kadambari Devi: Rabindranath Tagore’s Literary Companion | #IndianWomeninHistory

Recognition

She gained recognition when writers Annapoorna Venkatananjappa and Ba Ha Ramakumari spotted her at work and nominated her for a district-level award. After that she won the Karnataka State Government award in 2012, Kitturu Rani Chennamma award, Karnataka Rajyotsava award and National Citizen’s award of India in 2013, an Honorary doctorate from Tumkur University in 2014, until she finally received the country’s fourth highest civilian award, the Padma Shri.

Death

Narasamma’s faith in groundnuts and millets to maintain a healthy lifestyle proved successful until old age ailed her of lung disease. She was admitted to the Siddaganga Hospital and Research Centre in November 2018 and was later referred to BGS Hospital on November 29th, 2018. She died at BGS Gleneagles Global Hospitals in Kengeri, Bengaluru, Karnataka, on 25th December 2018 and was rightly honored by thousands of people from diverse backgrounds.

Reference

1. The Better India

2. The News Minute

3. DNA

Featured Image Source: One India

About the author(s)

(she/they)

A literature and gender and sexualities student, Saumya seeks to find explanations yet ends up with more questions unanswered. Identifies as an intersectional feminist, writer, and researcher. Solidarity always.