I think a creative writer should have a social conscience. I have a duty towards society… I ask myself this question a thousand times: have I done what I could have done?

Imaginary Maps. 1995. Mahasweta Devi’s interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

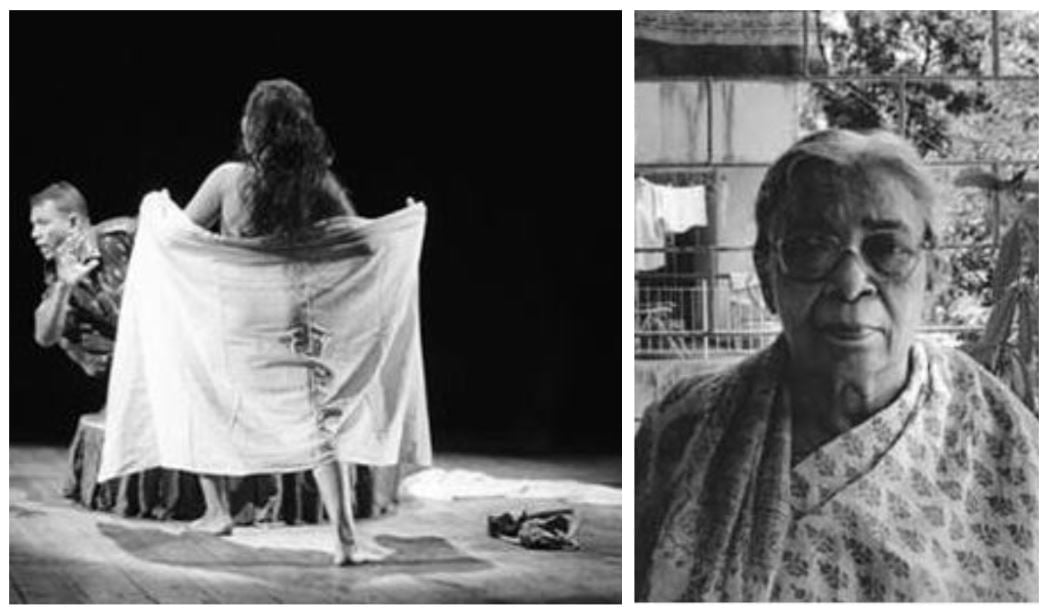

Draupadi is a short story of around 20 pages originally written in Bengali by Mahasweta Devi. It was anthologised in the collection, Breast Stories, translated to English by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.

Book: ‘Draupadi’, in Breast Stories

Author: Mahasweta Devi (translated by Gayatri Chakarvorty Spivak)

Publisher: Seagull Books, Calcutta (2010)

Genre: Feminist Fiction

Devi situates her story against the Naxalite movement (1967-71), the Bangladesh Liberation War (1971) of West Bengal and the ancient Hindu epic of Mahabharata, engaging with the complex politics of Bengali identity and Indian nationhood. The tribal uprising against wealthy landlords brought upon the fury of the government which led to Operation Bakuli that sought to kill the so-called tribal rebels.

Draupadi is a story about Dopdi Mehjen, a woman who belongs to the Santhal tribe of West Bengal. She is a Robin Hood-like figure who with her husband,

Ironically, the same officers who violated her body, insist that she covers up once she is ‘done with’. Intransigently, Dopdi rips off her clothes and walks towards officer

In both, the case of Durga and Draupadi, what happens to their body is a result of patriarchal voices which denies them agency.

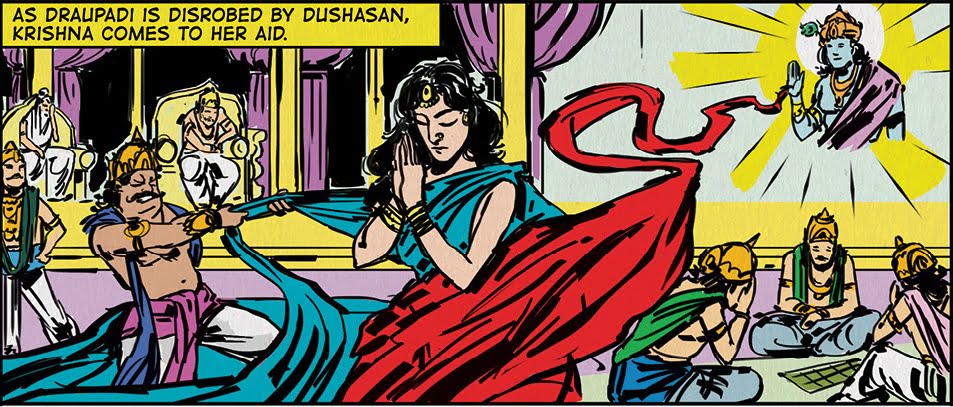

The story is stripped away from the Mahabharata’s grand narrative and royal attributes and situated in Champabhumi, a village in West Bengal. The ‘cheelharan’ of Draupadi is reconstructed in Devi’s story, subverting the narrative where Draupadi is rescued by a man, Lord Krishna. Instead, in Devi’s narrative, Dopdi is not rescued, yet she continues to exercise her agency by refusing to be a victim, leaving the armed men “terribly afraid”.

Dopdi is a woman of strong mind and will as she defied the shame associated with rape and sexual abuse, which is extremely relevant to India today. Especially in the onset of the #MeToo movement where many brave women came forward with their stories.

Dopdi is… what Draupadi — written into the patriarchal and authoritative sacred text as proof of male power — could not be.

Breast Stories. 2010. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Due to reading Draupadi with the knowledge that it was translated by Spivak I was constantly reminiscent of her essays: Can the Subaltern Speak? (1983) and The Trajectory of Subaltern in my Work (2003). Devi’s representation of Dopdi encapsulates what Spivak means by a gendered subaltern. Through the dislocation of the epic princess Draupadi to the tribal rebel Dopdi, Devi is able to present voices and perspectives otherwise unspoken and unheard of.

The Hindu mythology of the subaltern female body which is never questioned and only ever exploited is rejected by Devi. For

The character of Dopdi allows us to view the subaltern’s identity vis-à-vis the hegemonic structures seen through the policemen and Officer Senanayek. Thus, Dopdi’s body becomes a site of both the exertion of authoritarian power and of gendered resistance. Dopdi bears the torture as she is raped by many men through the encouragement of the voice of another man Arijit, that urges her to save her comrades and not herself. However, the attack on her body fades this male authority’s voice as she candidly reacts to the police. Her refusal to be clothed goes against the phallocentric power, and the exploitation of her body gives her the agency to step away from the hegemonic patriarchy of the policemen.

Also read: Book Review: Breast Stories by Mahasweta Devi, A Metaphor For Exploitation

Devi illustrates how any conflict or war results in the women’s body being the primary targets of attack by men. In the contexts of both the Naxalite movement and the Bangladesh Liberation war, both men and women are tortured, but it is much worse for women as they additionally undergo sexual abuse. Thus with Spivak’s concepts on the subaltern in mind, through Dopdi, Devi represents the gendered subaltern subject who exists at the periphery of society and dares to go against the existing patriarchal structures. Spivak has shown concern regarding the representation of the subaltern in the mainstream discourse on the basis that the subaltern cannot be represented; only re-presented. However, Devi’s use of polyphony not just re-presents the subaltern, it also explores the politics around the category of the ‘subaltern.’

Dopdi subverts the physicality of her body from powerlessness into powerful resistance.

Although there are many facets to the mythical Draupadi’s character, Devi focuses on the infamous incident where the princess is almost disrobed and subverts it to suit Dopdi’s context. Devi has always said that she is interested in the stories of ordinary people which is evident through the subversion of Draupadi’s rape. Towards the latter part of her life, she focused on presenting the narratives of ordinary people. In Draupadi, Devi has not allowed her female protagonist, Dopdi, to be submissive and conquered by the male-dominated society, unlike Draupadi from the Mahabharata.

Draupadi is a narrative that is universal in its portrayal of women as the most brutal victims of conflict and war. This approval on the part of Officer Senanayak in the story for the officers to ‘make her’ is reminiscent of the situation of Bangladesh’s Birangona and Japan’s comfort women. At the end of the story as she confronts the army officers with her bare body, the body that was violated and tortured is also in reverse used as a weapon. Even though Dopdi has been physically abused, she refuses to be emotionally wounded.

In Draupadi, Devi presents a strong woman who despite being marginalised and exploited, transgresses conventional sexual and societal standards. Dopdi subverts the physicality of her body from powerlessness into powerful resistance. She does not represent the tribal woman by romanticising her depiction of Dopdi but instead realistically re-presents her through simple language and complex emotions. Draupadi recognises a woman’s body as an asset through which they can resist the socio-political objectification of their bodies and overcome oppression.

Also read: Mahasweta Devi: An Eminent Personality In Bengali Literature | #IndianWomenInHistory

I urge anyone who has not yet read Draupadi to do so, and especially Bengali readers who can enjoy the words in the original language.

References

1. Devi, Mahaswata. ‘Draupadi’ in Breast Stories. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2010.

2. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. Can the Subaltern Speak?. (1983)

3. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. The Trajectory of Subaltern in my Work. (2003)

Featured Image Source: Women News Network

About the author(s)

Nikhat is a Civil Servant and Communications Manager for BBPC Poetry Collective. Her academic research interests include wartime gender-based violence and intersectional feminist historiography.

The Devi in Mahasweta Devi is not a surname but a suffix which denotes respect. So the frequent use of Devi indicating the surname of Mahasweta is meaningless.

this was a well-rounded analysis. i enjoyed reading this article after i read the story. great work!

That was a great article. It shook and disturbed me to reflect and question myself and my attitudes, opinions and life.

I always think of this story whenever I hear reports of daily gang rapes in India. I think of the Mahabharata Draupadi too. Gang rape was alive and well “then” too for it to be remembered in such stark detail in mythology. The violence, the terror, and trauma of rape is unspeakable. I also am reminded of Rajeswari Sunder Rajan’s piece on sati, the pain of immolation, and its deliberate spectacle that the female body is made to undergo by Hindu men. The fact that we have to read and re-read stories of collective trauma and pain to keep the resistance alive is depressing to me. The fact that we must keep reading and re-reading Mahasweta Devi even as it triggers remembered PTSD in us makes me furious even as an unraped woman — I cannot even begin to imagine the triggering of psyches for those who have faced sexual violence.

But yes, this is the #MeToo era where women do speak up (thank you, brave warriors and survivors!) — where they emulate Dopdi’s nakedness figuratively, but so many women remain unbelieved, are made naked all over again. No man’s life got ruined — but the female cheerharan continues. Men continue in positions of power and go on to harass and rape others. Gang rapes and further mutilation and immolation of female bodies are on the rise in India. When they don’t kill us in the womb or for dowry, throw acid in our faces, they manage to mangle us in a billion other ways. In so many ways, even though I fully agree with your analysis and Spivak’s (who has been a feminist poco stanadayani for so many of us), this story leaves me furious and powerless at the same time — again and again.

But I know. We cannot afford empty anger, or to give up. I don’t know how we change this so MD’s story of caste and gender based violence stops ringing true at every reading. I can only think of giving money to orgs that raise women’s voice, help victims and survivors, get out into the streets and continue to recite the Lastesis anthem in our homes, classrooms, offices, streets and bedrooms:

The rapist is you

It’s the cops

The judges

The state

The president.

Furious yet powerless.So true.