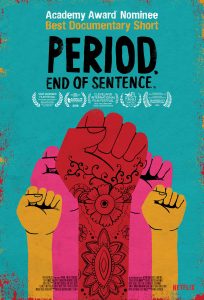

“What is a period?” The Oscar-winning documentary, Period. End of Sentence., opens with this question being put to several pre-teen girls living in a village in rural India. They giggle shyly, whispering to each other in embarrassment. The film then cuts to similar interviews with older women, who describe the negative impacts that starting their periods have had on their lives. These adults have lost their innocent carefree attitude that the younger girls have, and sit in front of the camera with a serious expression. Many of them have had to stop their education, others are angry at the fact that they cannot worship in their temples.

They talk about how the lack of information around menstruation has led to girls using dirty pieces of cloth, which is both dangerous and inconvenient. One woman says that she could not go to school because it was too difficult to constantly change out the cloth. One can sense quiet rage of these women at being forced into seclusion during their periods by the patriarchal nature of society. The way they channel this anger into their work — making pads to improve female hygiene and earn a living — is the focus of the film.

Directed by Reyka Zehtabchi and Melissa Berton, the documentary follows a group of women from a village called Kathikhera who work together in a small group to make a brand of pads they name FLY. These women become increasingly more open to speaking about menstruation, and are filmed as they go around the village raising awareness about the uses of pads. Not only are they educating their fellow villagers, they are also creating financial independence for themselves. It is empowering to watch these group of women build a life for themselves, together.

Sneha, who is central to the narrative, states that she wants to use the money she earns from the pads to fund her training for the Delhi Police. Another woman uses the money to get clothes for her brother, an act that makes her feel empowered as it is usually the brother who would use his money to buy his sister a gift. At the start of the documentary, these women find it difficult to even talk about their periods. By the end of the film, their confidence has grown and their pride in their work shines through.

Also read: The Journey Of Menstrual Hygiene Management In India | #ThePadEffect

The idea for the documentary was born from the brave activism of a group of female high-school students in Oakland. The girls decided that they wanted to produce a film about the taboo around menstruation to raise funds for pad machines that could be placed in developing countries. Their goal was to help women in these countries create a micro-economy of their own through selling the pads.

One of the students’ parents contacted Reyka Zehtabchi to direct the film; the Iranian-American producer did not hesitate to say yes. The idea for the film came from a genuine desire to help, and the team had to apply sensitivity in portraying the women in a respectful way. One of the students involved, Helen Yesner, told the International Documentary Association that she “never wanted it to be a film that said, ‘Look at these poor women, at this backward village'”, adding that the United States also has issues with how menstruation and pads are talked about.

Far from applying the first world, ‘global saviour’ type of narrative to the film, these students were acutely aware of their privilege and their position as an outsider and exercised a healthy amount of sensitivity. They worked with local organisations such as Action India, a grassroots feminist organisation in India and enlisted the help of famed Indian director Guneet Monga. They also hired Mandakini Kakar, a local producer and translator, to help them communicate with the women of Kathikhera and overcome the language barrier. Thanks to her, at least sixty percent of the documentary shows the women speaking in Hindi.

Also read: Meet The ‘Pad Women’ From Assam Who Are Spearheading Access To Sanitary Products

The women in the film also speak about the wider context of their work. Suman, one of the women who makes and sells the pads, says at one point that “when there’s patriarchy, things take time.” She acknowledges that their work has not yet succeeded in completely changing the way women’s menstrual needs are being talked about in the village, yet her statement is also a symbol of hope. Sneha also speaks about the future with optimism, stating that it will eventually become easier to gain access to pads, that one day there will be FLY pads sold in every shop. The women named the brand of the pads FLY because with they wanted women to ‘rise and soar’, capturing the hope that they have for the female population of Kathikhera.

With the film just having won the Oscar for Best Documentary Short Subject, there will certainly be an increase of awareness around women’s access to hygiene products. In fact, Zehtabchi revealed in an interview with Refinery 29 that they managed to install two more pad machines in neighbouring villages because of the sudden demand for them. However, there is still a long way to go before every the stigma around periods is destroyed, until women can live totally uninhibited by something that is a natural phenomena. “We’ll get there one day,” says Suman.

References:

Featured Image Source: Livemint

About the author(s)

Beverly Devakishen is a final year student at the University of East Anglia studying Literature and History. She is interested in Asian history, as well as issues around gender and sexuality. She is deputy editor for The Queer Review and has done journalism internships at newspapers such as The Guardian.

While it is quite powerful that periods is entering mainstream arena, the movie is restricting its narrative to just disposable pads production as the solution – which is problematic and diminishes the complexity of menstrual equity and awareness around it. Rather than the end of a sentence, this should be the start of reclaiming menstruation with informed choices and dignified menstruation, where access to non-toxic and affordable hygiene products (all of it, not just disposables) becomes the norm.