Trigger warning: Sexual harassment, Child abuse, Trauma

There is a documentary on Netflix called Rocco (2016), about the porn star Rocco Siffredi. Beautifully shot and movingly narrated, it’s a complex exploration of sexuality, desire, religion, faith, sin and the tension between these. “My sexuality is my devil,” says Rocco; after three decades, he wants to leave porn, so that “the devil between my legs won’t be a part of me anymore.”

It’s impossible not to get wrapped up in its subject’s obsessive interrogation of why he does what he does, what he seeks through it, how it has been affected by the people around him and how the people around him have been affected by it. Rocco interviews the women who come to his production house, asking in his broken, heavily accented English, “What was your sexual life like, when you were 14-15? When did you first start to masturbate? What kind of sex do you like?”

As a viewer, it’s an unnerving experience. One can feel the subject turning his gaze on you, and almost involuntarily, at one point, I began answering these questions myself.

Part 1

When I was about seven, I was sexually molested for the first time.

I was with my mother, on a bright day in Kolkata. She was holding my hand and we were passing in front of the kindergarten I’d been attending only a few months earlier. We walked past the coconut water-sellers; I was distracted by them; I loved coconut water. I felt a hand on my right buttock, a man’s hand; I have what I think is a memory of a man in a check shirt, passing by in a flash (or was it striped?). I do not remember his face.

I giggled, and told my mother, “That man just placed his hand on my bum.”

My mother dragged me aside, and said, “What?”

She looked into my face.

“Tell me, next time,” she said. “Always tell me when things like this happen.”

I was ten when I was laughing with my father in the front room of our flat in Mumbai, one leg folded at the knee up on the seat of my chair, when I felt eyes on my hand, on my legs. The man who we’d give clothes to for ironing was at the door, looking directly at me. I knew my underwear had been visible as I’d laughed. I refused to step out of the door for weeks afterward, trembling, terrified to pass the shop in front of the house, certain I’d be raped.

I remember the boys I liked in my school in Mumbai. I remember the day one of those boys said to his friend, perhaps not understanding what he said, “Chal, Rushati ka balaatkaar kartein hain.” Let’s rape Rushati. I choose to believe that he did not understand.

I was twelve when, on a vacation in Chennai with my parents, a man pinched my ass. I stared him down and watched him walk away, glaring at him, and I didn’t move, didn’t shout. I was sixteen when I was out with my parents back in Kolkata during Durga Puja and a man sleeping on the side of the road sat up, looked me up and down as I stared him down, and told his friend, “Chehera takey dekh.” Look at that body. I was so humiliated that I felt tears spring into my eyes. On our way back, he was asleep, and I imagined picking up the brick next to his head and bashing his skull in with it, over and over and over again until his brains and bones and blood become one thick jelly.

I didn’t tell my parents.

Part 2

As a child, it’s difficult to imagine that your parents existed apart before you were born. My parents had been destined to meet by the stars, I thought.

So when they told me that years before my birth, my mother had once lapsed into a near-catatonic state of darkness, I believed that simple sadness was explanation enough. She’d been diagnosed with tuberculosis around roughly the same time, and a few months before that, she’d lost her best friend to a freak accident. She’d been taken to a doctor, a psychiatrist she disliked. I even knew things I wasn’t allowed to tell: how she suffered from urinary incontinence at the time, how this was the beginning of her obsessive cycles of washing and cleaning her environment, how afraid she was of house guests or of spending the night elsewhere, how ashamed she was of her affliction.

My mother had been a Political Science graduate, with an MA in Journalism. She was vivacious, her friends told me. She was the outgoing leader, the smiling young woman I saw in yellowed photographs taken outside her university. She was a translator with the central government- one of four people, among thousands, from our state to qualify for the job- when she first met Jamal*.

My mother would not leave me alone with any man except my father, for any length of time in my life – not even my own cousin.

My mother loved Jamal out of revenge on the handsome, well-to-do Kishalay*. He was beautiful – fair, tall, with black hair and an arched nose. That’s how I imagine him, anyway. He was from a ‘good family’, one of the aristocratic

I asked her why they broke up. She didn’t, she said. He broke up with her, around the time her depression first started manifesting. “I don’t think we should be together”, he’d said, “if we’re both like this”. I was furious, but my mother wouldn’t hear a word against him. He was right, she said. He never deceived me. It was my fault I couldn’t make him stay.

Also read: #MeTooIndia: How Toxic Masculinity And Misogyny Caused Me Trauma

By the time Jamal left, my mother couldn’t go out of the house alone. She could no longer go to work. H

“They treated her like a girl in a bazaar,” my father told me once. Stupid girl, loving a Muslim. Stupid girl, letting him beat her senseless. Stupid girl, letting him know where she lived and exactly what could be done to the people she loved.

My mother left that job she was so proud of. She got married to my father, and she had me.

A few years ago, my mother ran into an acquaintance. She found out that Kishalay is married now.

I think that was around the time that I first realised that marriage doesn’t really have much to do with love.

Part 3

I’ve never been comfortable around men.

My mother would not leave me alone with any man except my father, for any length of time in my life – not even my own cousin. Her first question, in any situation that involved a male teacher or a male colleague or a male boss, was, “Shey ki aloo?” A coded, vulgar way of saying, is he likely to molest you?

She refused to let me go anywhere on my own, forced me into baggy, shapeless clothes I loathed to hide my larger-than-average breasts, repeatedly wished in front of me that my breasts could have been smaller and advised me not to talk to male teachers or stay alone in rooms with male friends.

I remember one occasion very clearly when she screamed at me when I chose to wear fitted tops and jeans at the age of fourteen, “You’re child – look like a child! Don’t you know you look like a slut in those clothes?”

I grew up learning not to trust the world around me, walking on eggshells all the time.

But she still couldn’t protect me: not from the men on the road and not from the boys in my class.

Part 4

About a year ago, I had a strange experience.

I was working at a literature festival. An author I’d admired for years was sitting beside me at the after party. I’d interviewed him a few hours previously; we had got on famously. Everything was fine.

To be a woman is to be constantly gaslighted – constantly told that there’s nothing to be afraid of even while reinforcing the idea that if something harmful does happen, it’s your own fault for not being careful enough.

And then he reached up to brush off something – an insect, I think – that had landed on my shoulder. He apologised as he did so, saying, “I’m sorry, it’s just that I think it might bite.”

And I froze.

I could feel my throat closing up, a cold feeling stealing over my heart. I couldn’t understand what was happening, but suddenly, I couldn’t even look at him. I got up and moved away and shared a chair with a friend for the rest of the meal. The next day, I met to interview another author from the same group and I didn’t acknowledge him. I stayed away, hating myself, but trembling inside, with a seven-year-old’s voice buried somewhere within me, whispering, “But what if he raped you?”

Part 5

In July 2017, I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

It was a multi-faceted diagnosis with multiple symptoms and origins, but a key aspect was the conclusion my therapist reached: that I am afraid of my own sexuality.

I am afraid of being seen as a sexual creature, and of behaving in a way that might ‘invite’ sexual advances from men. I am afraid of advances coming my way even in reasonable situations, such as on a dating app. I am afraid of boys and men in general, and I am afraid to trust anybody, anywhere, even and especially myself.

It had never occurred to me that what I experienced, growing up, was worth counting as trauma. It hadn’t occurred to me when grown men salivated over my twelve-year old, overgrown, ripe body, and made no pains to conceal it. It hadn’t occurred to me when my own mother saw me as a sexual creature first and a young girl later, probably because of her own experiences. I internalized it over the years, and now I am afraid of the very act of sexual intercourse and anything that precedes it, because in my head, it is inextricably intertwined with violence. That is the only information I have ever been fed, over and over and over again, in my home and outside it.

-x-

We teach our boys that dominance is achievement. We teach them to confuse violence with sex. We teach them to feel threatened if this equation is disrupted. We teach them that they’re entitled to a woman’s time and emotional spaces and that if the woman refuses, they have the right to abuse her verbally, emotionally and, in the most visible cases, physically. And we teach our girls to accept this, and enable it, and conform to it, and stop other girls from speaking up. And then we create a toxic, noxious vat of sexuality and gender roles that sets the stage for the rest of their lives.

To be a woman is to be constantly gaslighted – constantly told that there’s nothing to be afraid of even while reinforcing the idea that if something harmful does happen, it’s your own fault for not being careful enough. It’s to be constantly told that you’re not good enough, that you can’t be and shouldn’t be, and then blamed for it if you begin to believe you aren’t. It’s to be constantly paranoid, constantly be hyper-vigilant: why is he insisting on getting my phone number? Will he continuously harass me if I give it to him? Will they ask me why I gave it if he does and I seek help? It’s to constantly second guess your version of reality, even though you know what you feel: what if he didn’t mean to make me feel uncomfortable? Was I rude to him? What would he have done if I wasn’t?

It’s to constantly, constantly, constantly ask yourself – is it my fault?

-x-

And that is how I have framed my sexuality: not in terms of who I can fuck, or who will fuck me, but of security, and trust, and the complete lack of these. At the age of 23, I’ve never made love. The perpetual state of doubt I live in imprisons my body in a miasma of despair. On some nights, when I’m so lonely it feels like something is eating away at my bones, gnawing me open wider and wider and wider, it feels like too much to bear.

I want to love. I have so much love in me, so much to give, and so much to feel. I want to know what it feels like to be to know and trust that someone finds you desirable, and to desire them in return without feeling guilty, ashamed, disgusted, or wrong. There is so much disgust for myself in my own head, for my own body, that it’s no wonder I project it onto others, accepting without questioning that they find me repulsive.

-x-

“This is what I don’t understand,” says Siffredi, as I watch. The girl on screen, soft, sinuous, naked, bites down on his thumb, her gaze changing as she looks up. She no longer looks like she is acting; I know that look; I think I’ve seen it somewhere. Her hair falls over her face, some of it in her mouth. I feel an ache, a long-forgotten ache somewhere I was once unafraid of. “How can it take so long to understand yourself?”

“I don’t know,” says the girl. And as she says it, with a sudden rush, I know what I want. I know what I want to be.

I just want to be normal.

But I’m not sure what that means anymore.

Also read: To All The Traumas I’ve Lived

*Names have been changed.

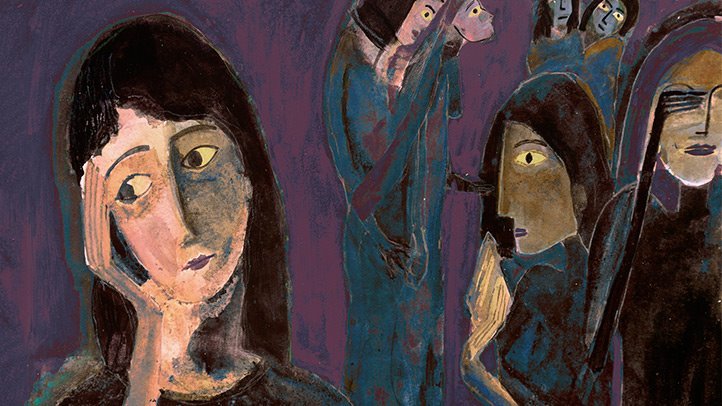

Featured Image Source: Everyday Health

About the author(s)

Rushati Mukherjee is a Producer of the news podcast BBC Minute India, for BBC World Service. They have written for national and regional outlets as a freelance Features journalist. They are on the Advisory Board of the British Council's international journalism conference, Future News Worldwide. They are also a translator and a poet, and have been an official blogger at the Jaipur Literature Festival. They can be reached at @rushatim on Twitter.