Trigger warning: Rape, Sexual assault, Graphic violence

Netflix’s newest addition to their documentary series Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes chronicles the murders of the serial killer Ted Bundy, who attacked, beat up, sexually molested, and raped approximately 30 young women in different states of the United States of America between 1974 to 1978. The docu-series speaks to several important actors who played key roles in investigating the crimes and taking Bundy to court.

While Bundy mostly targeted women in the age groups between 18 to 22 or 23, one of his last victims in ’78 was a young girl of 12, named Kimberly Leach, who was kidnapped by Bundy from school, and brutally murdered. Her body was found almost more than a month later, and the then Sheriff of Salt Lake County, where Kimberly was from said something that resonates with most victims till today – especially victims who are girls or women. He said that when the search team found Kimberly’s body, he broke down – he hadn’t cried since his teenage years, he said, but looking at that girl’s body lying in the woods made him cry. He followed this up with “Kimberly was such a sweet, obedient girl.”

Would his reaction have been different if Kimberly hadn’t been a sweet and obedient girl? Would he not have felt angry that such a heinous crime was committed if, say, Kimberly was impolite or disobedient? All of the 30 odd women that Bundy murdered were not found, but for the ones that were found, the narratives that came out on TV or in print, was that the women were so sweet and nice, and “how could something like this happen to someone as nice as her?”

Would he not have felt angry that such a heinous crime was committed if the

victim had been impolite or disobedient?

The narrative of the ‘good’ victim or survivor of a crime has plagued our news for a long time. Whenever a crime takes place, especially heinous crimes like rape or sexual assault, especially involving a woman, the popular narrative everywhere becomes that because she was so sweet or so caring and loving that it is unfair something like this could have happened to her. The crime takes on a different meaning in the backdrop of the woman’s good nature or affable demeanour. When India’s Daughter released in the wake of the December 16th gang rape of a woman paramedic in New Delhi, there were so many conversations in the documentary of what a good person she was to her friends and her family.

But what if the narrative was different? What if she hadn’t been a good woman, in the typical sense of the term? What if she had been negligent to her parents, or she had a lot of affairs, or she was not friendly to everyone? Would it then have been okay that such a crime was committed against her? Conversely, other narratives around crime also revolve around the independent, fierce woman in an unforgiving manner.

During an interview that I took as part of a research on witch hunting in Jharkhand, it came forth that one of the victims of witch hunting in a village in the state had been a fiercely independent woman – she had moved out to live in with her partner, had a child with him and eventually left the partner to come back to her natal home. She worked as an Anganwadi worker, and was termed a witch, and subsequently murdered. Narratives around this incident were mostly that she was an independent woman and hence defying the patriarchal societal standards of what a good woman should be, and hence she was labelled a witch.

When such narratives are encouraged in popular media, it encourages one of two notions. One would be that by attaching the character traits of a woman to the crime perpetrated on her, we are playing into the patriarchal idea that the crime has something to do with how she was as a person. And this is also most evident when we speak about crimes like rape, sexual assault, domestic violence or dowry-related violence, crimes which are attached to the body of a woman or to the gender roles of wife and daughter-in-law. When we speak of crimes like deceit, theft, or forgery, we don’t delve into the character of the victim or survivor in these cases. Neither do we discuss the character of the victim.

The atrociousness of crimes like rape, sexual assault, witch-hunting or murder should not be decided based on the victim or the survivor.

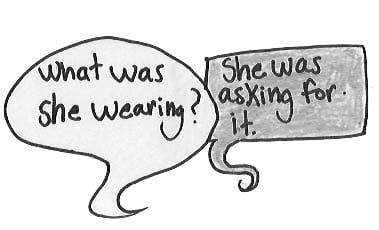

The patriarchal and sexist nature of the society we live in tries to control the bodies of women, so they feel like there must be a direct correlation of survivors of such crimes and how they were as people. While popular narrative might try to defend its stance by saying that the aim of these character judgements is only to bring out the stories of the victims or survivors. But if we only speak about how nice and sweet the woman was, we are only perpetuating a certain idea of who a victim can be, as opposed to the fact that any woman affected by these crimes has faced a gross violation of her rights. Victim blaming is the eventual consequence of this story: “but why was she out so late?” or “why was she wearing those clothes?” or “why was she out with a man who wasn’t her father, brother or husband?”

Also read: Book Review: What We Talk About When We Talk about Rape By Sohaila Abdulali

The atrociousness of crimes like rape, sexual assault, witch-hunting or murder should not be decided based on the victim or the survivor. There has to be an understanding that these crimes violate some very fundamental rights of a human being, and that no matter what the disposition of the woman was – whether she was quintessentially good or bad – does not, under any circumstance, matter. Our laws don’t provide graded punishment under these crimes based on society’s perception of the woman. We should, too, stop passing such value-laden judgments about them, especially in the wake of these crimes.

Narratives will be many – but when these narratives form our front page

Also read: Victim Blaming: A Trope As Old As The Hills

While I understand the Ted Bundy Tapes speak of a different time, and we have progressed several decades after that, it has resurfaced again, thanks to the documentary. The question now should not be why the victim or survivor was attacked, but what patriarchal, sexist ideas allow these crimes and how we can fight that.

Featured Image Source: The Commander

About the author(s)

Himalika is slowly beginning to get the hang of being an adult, despite being a bad cook. She will take most things with a sense of humour and is constantly striving to infuse feminist practices in her research.