A report by Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and UN Women titled Women In Politics (2017) states, “As on October 2016, out of the total 4,118 MLAs across the country, only 9 per cent were women.” India ranks 151th among the 190 countries and 5th among the 8 South-Asian countries.

Equality in Politics – A Survey of Women and Men in Parliaments explains various aspects relating to women’s political representation and parliamentary governance. Overall disparities follow the same trend with the lack of confidence and finance being the major deterrent that prevented women from entering politics. These stats along with the recently released ‘manel’ report by the Network of Women in Media (NWMI) 2019 sheds light on the ingrained prejudice against women within the Indian news media.

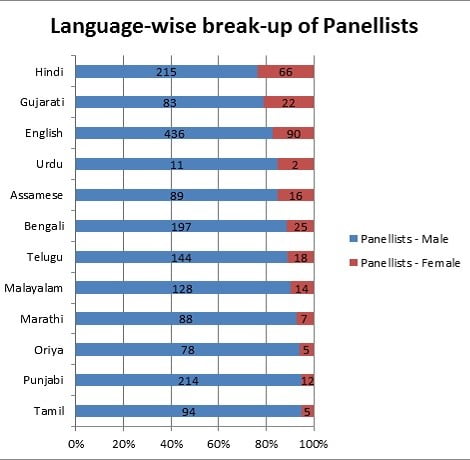

Panel discussions occupy prime time viewership in the TV news universe, irrespective of the language. The

Image Source: Panels or Manels, 2019

With better literacy, health and other human development indices, the state of Tamil Nadu has often revelled in the numbers that made it a ‘class apart’ within the country. The low score is telling of the accepted model of toxic masculinity and cultural patriarchy, that encompasses Tamil society.

While the male-led leadership fight amongst themselves, to claim the ‘true’ Tamil identity, women get the short end of the stick.

This media representation, however, explains the deeper hypocrisy that is imbibed in the Tamil society. Tamil pride has often been a merger of distinct linguistic and cultural identity. The yesteryear values based on ancient Tamil texts, glorify chastity, virginity, and a submissive female who happily lays down independence for the family or her man’s wishes.

Simply put, the ideal Tamil female is the virtue of chastity and the Tamil man, an epitome of virility. The proponents of this identity beginning with the speakers of Dravidian movement to many of the modern-day political stalwarts stick to this image adherently. This so-called ‘Tamil’ identity has sexist undertones, “middle-class morality” which are often glorified to forge a partnership among the common people.

In Tamil Nadu, feminism is often angled with the words of two very distinct personalities, the poet Subramanian Bharati, and Periyar (the founder of

According to the election commission report, in 2016, more women turned up to vote when compared to men. While the vote matters, women as leaders, candidates do not get the encouragement or support. This is in line with the superficial streak of female empowerment practised by regional politics.

- In the last state assembly elections in 2016, the AIADMK and CPI(M) fielded 12% and DMK, 10%. The Congress fielded three of the 41 candidates (7%) the party.

- Women MLAs accounted for 3% to 10% of the Tamil Nadu state Assembly.

Image Source: Panels or

Stage culture of Tamil oratory can be an empowering platform for aspiring female leaders but ‘a handful representation’ of female speakers are pigeonholed to score political points. The point of female empowerment or representation gets lost in the wider politics between the parties. This spills into the outrage drama that follows shouting-matches linked to ‘controversial’ statements.

While this passes for prime-time journalism, diversity and representation in these panels are more than often absent. In between film trailers and other product placements, the debate is usually carried on by the same set of women, handpicked by the channels for their political leanings. While representation by women in various issues

The whole concept of language bonded nationalism has been the cornerstone of Dravidian politics. While the male-led leadership fight amongst themselves, to claim the ‘true’ T

The state has long had an authoritarian female leadership by the late CM Jayalalitha. As a head of a Dravidian party, unapologetic of her caste, religion, she had a distinctive governance style. Absolute subservience with her central

Also read: Dalit Women in Media and Politics Conference: When #DalitWomenSpeakOut, Revolution Beckons

Though the state has very good indicators with regard to literacy, women still face challenges because of the

- Total literacy rate in Tamil Nadu has shown an increasing trend over the years, increasing from 62.66% in 1991 to 80.33% in 2011.

- 14 districts have female literacy rates above the State average that is, above 73.86%.

Women leaders of the state have in the recent years have only been meme topics and insults on-stage by politicians. Even insults hurled between men on-stage bear references to their mothers, often demeaning them. This downgrade in stage decorum is a far cry from the flowing Tamil language used to garner public support for the party, during earlier times. This also goes hand in hand with that way political parties slowly ease out women from active participation.

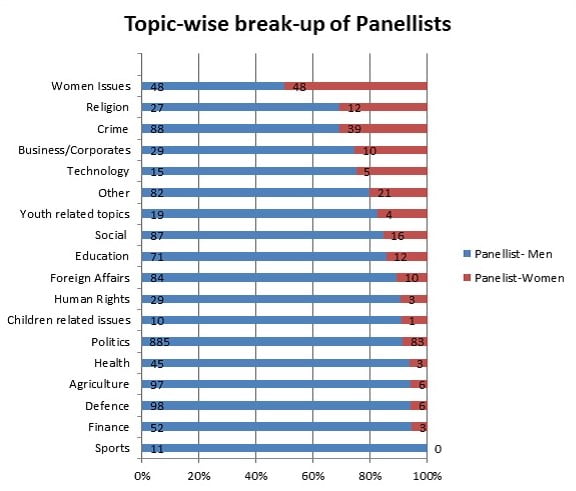

Only 5% of the professional and independent analysts featured on panels were women

Politics has become a man’s domain and women mostly get typecast as symbols for virtue, chastity or as whores. The latter word had caused quite a stir in the state earlier last

While systemic patriarchy and caste deter women as political candidates, grassroots are an active platform to inculcate female leadership. In this intrusive social media age and the social reality of “TV culture is Tamil culture”, media can be effective to provide role-models.

Gender bias, in the panel discussions, the conspicuous absence of women’s point of view, and the lack of diversity among the women represented are serious causes for concern. The explicit lack of role-models, female leadership continues to manifest as an

Only 5% of the professional and independent analysts featured on panels were women; the corresponding figures for party spokespersons and subject experts were 8% and 11% respectively. Politics dominate these prime-time debates and by extension our daily lives. On the other hand, in discussions on politics, which constituted nearly half (45%) of all panel discussions on news television, only 8% of the panellists were women.

In a 2015 survey on media and gender in India by the International Federation of Journalists (focusing primarily on patterns of employment and working conditions), only 6.34% of the respondents felt that women were shown as ‘experts/leaders’ in the news. A

The early gains of the Dravidian party and the popularity of the Congress-old guard in the state

References

1. Equality in Politics: A Survey of Women and Men in Parliaments

2. Panels or

3. Election Commission Of India reports for Tamil Nadu assembly elections 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016

4. Tamil Nadu Human Development 2017

Featured Image Source: Livemint

About the author(s)

A homemaker trying to wedge feminism into daily life. Ambica enjoys reading and is a news junkie. She loves political satire, especially by female comedians. Her other interests are films and plays.