Posted by Riddhi Jhunjhunwala

When the Right to Education Act was first passed in 2009, there was no question that we were witnessing a landmark moment as a nation. It was drafted as a progressive and a resolute measure to guarantee free and compulsory education for all children in India between the ages of 6 and 14, irrespective of gender or socioeconomic status. 10 years on, however, we are far from realising the well-intended objectives of the act. In a timely report that was published by the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE) in 2010, the facts were laid bare: it estimated that an additional 1.2 million teachers are needed to rightfully fulfil the Right to Education Act.

This lack of teacher availability is symptomatic of a deeper issue. According to the ASER Report published late last year, more than half of children enrolled in Grade Five (10-11 years old) are simply not able to read a text created for the Grade 2 curriculum. Such a statistic is deeply shameful, yet hardly surprising to the average Indian – the dismal condition of our education system is no secret. What this means that while students have been provided superficial avenues for education, they don’t seem to be truly learning – which has serious social repercussions. Specifically, the effects on the female demographic are most damning – not only are such learning outcomes discouraging parents from sending their daughters to school, they reinforce misconceptions about the female body and women’s health.

Right to Education Act was drafted as a progressive and a resolute measure to guarantee free and compulsory education for all children in India between the ages of 6 and 14

The lack of health education is one of the most gaping chasms in the Indian education system and is indicative of a regressive society. Issues of sexual health, sexual rights, sexual activity, pregnancy, prenatal care, breast cancer, cervical checkups, even menstruation, are pushed under the carpet in the hopes that an elder woman at home will ‘dole out appropriate advice’. However, with low literacy rates and constant new developments in the field of health, it is the responsibility of educators to help our next generation better understand the realities and resources dedicated to their personal health.

Also read: What Happened In SRM College: The Rampancy Of Sexism In Educational Institutions

In terms of health measures, government schools across India provide students with Mid-day meals, in an effort to improve nutrition, along with some form of a physical education class; furthermore, girls are given a small pack of sanitary napkins every month. While there have been efforts to improve access to the basic necessities associated with women’s health, young women across India are not being told (enough) about the importance of safe sex or the need to conduct breast self-examinations (BSE) as they enter their teenage and young adult lives. In not addressing this issue effectively, we are not only putting our female population at risk but perpetuating a vicious cycle within our educational infrastructure with long-term damaging consequences.

It is high time that something is done about this, and I believe and there need to be efforts taken specifically to improve access to women’s health education and resources, especially to educate women on changes within their own body and dismantle prevalent stereotypes regarding women’s capabilities – in order to take steps towards women’s empowerment and autonomy. It is time we begin changing the existing cycle of public education, and begin bettering our schools to not only teaching quality math and science but also include classes and menstrual hygiene workshops.

Taking a closer look at the situation with regard to women’s health in India, it is apparent that besides the old world ills of malnutrition that continue to uniquely plague women, we are also suffering from a rise in lifestyle diseases as well. This reflected in the difference in economic and social status, shared between rural and urban women respectively. The impossible situation that women find themselves in navigating the weight and the imposed burden of their bodies. Nutritional deficiencies, unsafe deliveries and complicated deliveries and infectious ailments – the gendered obstacles to healthcare services is vast and wide-ranging

The public consciousness is slowly but surely recognising the ways in which women continue to suffer. But suffering isn’t the standard condition for women.

In urban areas, you see a huge problem with the other end of the nutrition where you get access to poor quality but calorie-dense food, so you have obesity and lifestyle diseases. In poorer situations, both rural and urban, hygiene and sanitation are a huge problem among women. Another thing that is critically important is domestic violence, which I don’t think is appreciated enough as a public health problem.

We can’t let women remain painfully bline.

We are currently in the midst of awakening – in terms of women’s emancipation and realisation of women’s rights. The public consciousness is slowly but surely recognising the ways in which women continue to suffer. But suffering isn’t the standard condition for women.

What does that mean for the students in our country? For the future change makers and leaders of the country?

Also read: From Kerala To Gujarat: How Rightly Portrayed Is Sexuality In Indian Textbooks?

The implicit entitlement and ownership over women is evident in the nature of the crime itself: the needless investigation of women’s bodies, the onus on ‘proof’, the callous dismissal of trauma. Women’s bodies are women’s bodies, and they should be allowed to hold complete social autonomy.

Riddhi Jhunjhunwala is a grade 11 student at the British School, New Delhi. She is an avid pianist and dancer, and a passionate advocate for women’s rights. Riddhi has founded her own social initiative where she aims to educate women about various illnesses that impact women and provide a safe space to encourage conversation and discussion about these topics with each other and health professionals.

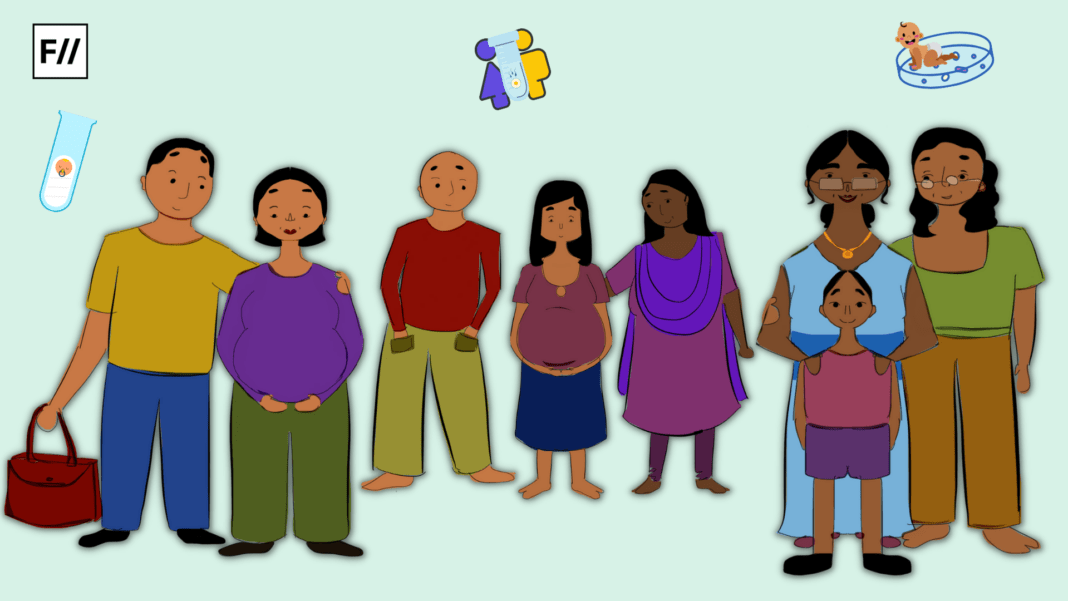

Featured Image Source: World Bank Group