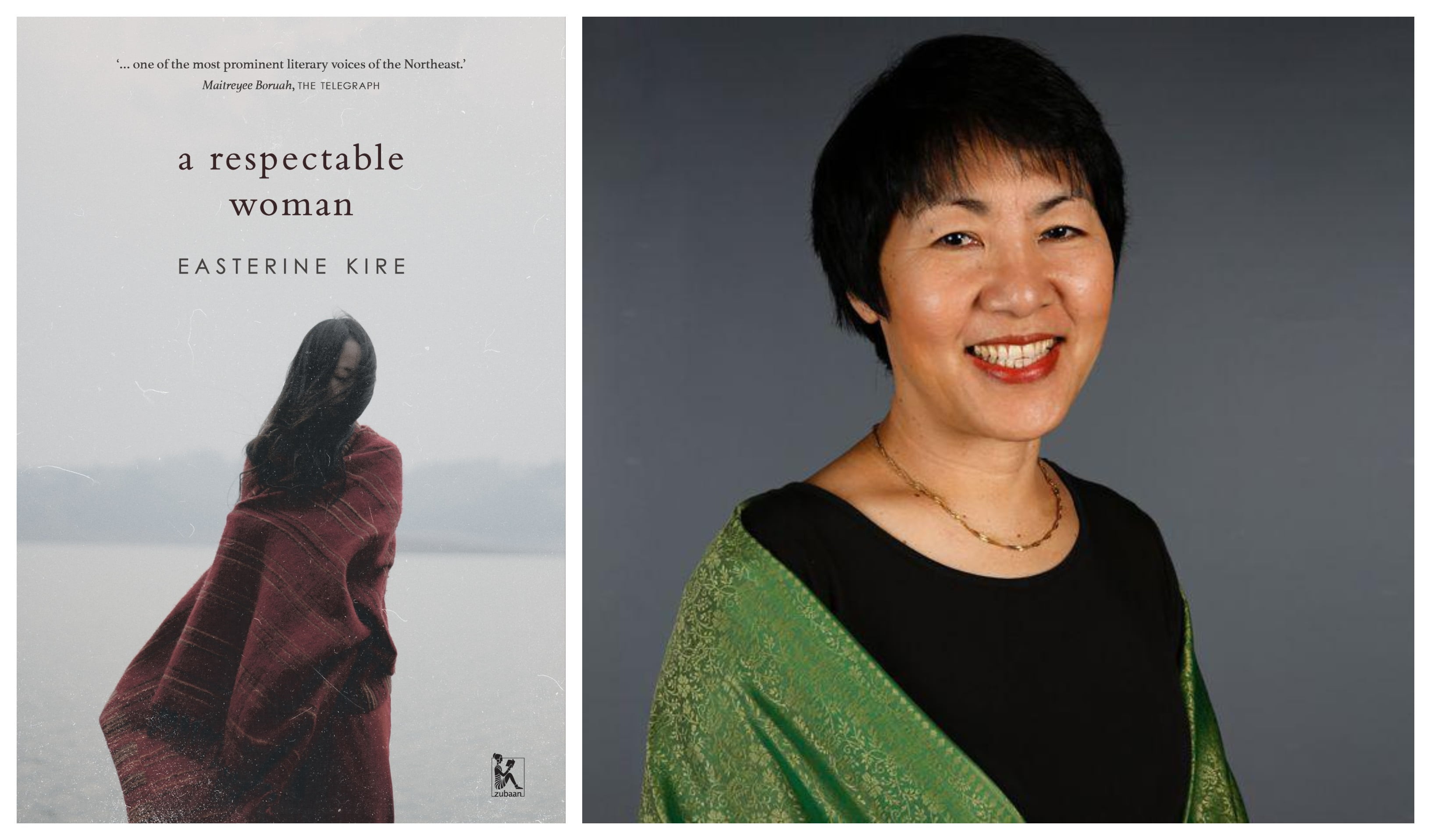

Divided into 3 parts, A Respectable Woman travails the psyche of the Naga community during and post the 1944 Kohima War. The author, Easterine Kire, sketches raw human emotions in the face of a gruesome war on temporal and spatial lines in her novel.

Author: Easterine Kire

Publisher: Zubaan, 2019

Genre: Fiction

The horrors of the Kohima War are recounted after 45 years of muted silence by the mother of the narrator, Kevinuo. The mother, Azuo, and the narrator recognize each other as ‘friends, and not adversaries’, as the former chronicles the barbarity that the Nagas were subject to as they fought against the Japanese.

Also read: Book Review: Waiting By Nighat Gandhi

The 1944 war left Nagaland ravaged as the land was torn asunder by the invading Japanese. They captured houses, razed some of these to the ground, and also monopolised food provisions and other essentials. The dehumanizing impacts of the war are combatted through the humane efforts of the Nagas and the locals as they try to restore order as soon as possible post the war. The terror of the incident of the bodies of Japanese soldiers found stuffed in the oven of a bakery is alleviated by the humanitarian act of a Naga woman defending a Nepali soldier of Assam Regiment from the Japanese by calling him her son, and receiving the soldier reciprocating the same.

The District Commissioner, DC Pawsey initiated the reclamation of the land soon after the end of the War. He and his men distributed timber, food provisions, and other essential paraphernalia to the afflicted people, and aided in opening and repairing schools, hospitals, churches, and shops.

When Pawsey insisted on building a road for the convenience of the villagers, he is in for a shock since they believe that the construction of a road would lead to conflicts between clans, as they had always minded boundaries through topographical features, something that the ‘white man’ Pawsey could not fathom for whom boundaries need to be tangibly pronounced.

For a work which is beautifully written and peppered with metaphors that further add to the poignancy, the metaphor of the mad man setting fire to one house and destroying the rest of them in a domino effect hammers home the point of the mindlessness of war.

While the people come to terms with the trauma of the war, Kevinuo’s Azuo has her own share of personal griefs. Her mother never recovers from the loss of her youngest son, and later when she loses her elder son who served in the Assam Regiment, death comes as a mercy to her.

In a close-knit community, grieving is as much a community affair as celebrating. The solidarity also stems from the trauma that the community collectively underwent during the wars, resounded and cemented by Azuo’s claim that war makes one benevolent.

The solidarity also stems from the trauma that the community collectively underwent during the wars

Incidents of such solidarity are scattered throughout the book .From ‘Amo’s Wives’ to letting out houses and sharing food, hatred and benevolence become the shade of one colour.

Post the 1944 War, another incident which mars the harmony of the Nagas is the withdrawal of the English from independent India.

Conditioned to stay under the rule and directions of an authoritative figure, the retreat of the English renders the Nagas sad, so much so that they equate the withdrawal to the loss of parents. This ‘loss’ leads to a conflict between the Indian Union and the Nagas, the former wishing to enclose the latter within their territorial folds, while the latter fighting for their sovereignty, eventually giving birth to the Naga National Council in 1946.

The Naga National Council (henceforth referred to as NNC), at loggerheads with the Indian Union have to bear the brunt of fighting for their autonomy. Incidents of rapes, murders and killings abound and curfews become commonplace.

It is interesting to delineate the theme of ‘nationalism’ that becomes prominent in the face of the conflict between the NNC and the Indian Union. The former sees Nagaland as their ‘mother’ and their idea of nationalism is fighting for their mother’s freedom from the unwarranted takeover by the Indian Union, this estrangement further echoed by Kevinuo’s father who tells her that ‘India is far away.’

Also read: Six Women’s Movements in the North-East You Should Know Of

The frustration is so rampant that the Naga men take to drinking and venting out the same on their wives and family. Drinking becomes nothing short of a social nuisance, resulting in a friction between the church women and the brew women. With the Prohibition Act underway, the ban on liquor and the liquor menace as a whole in Nagaland draw parallels from the Prohibition in America.

Despite sadness that percolates the book, there are incidents of gaiety as well.

A book that lays bare the raw fabric of humanity, Kire’s rendering of an account of domestic abuse is bound to leave one teary-eyed. Kevinuo’s friend, Beinuo, who had always been resolute on ‘beating back’ a husband if he ever dared to raise his hand on her, settles into a life of complicity and complacency after her marriage to a well-off man, who had learnt ‘never to take a no for an answer.’ She is doubly victimized after giving birth to a daughter and raising her up. She later dies of a fractured skull at the hands of her husband, and in a classic case of poetic justice rightly delivered, her husband, Meselhou too dies of a fractured skull.

She is doubly victimized after giving birth to a daughter and raising her up.

Kevinuo adopts Uvi, Beinuo’s daughter and decides to bring her up as her own. A practice not ‘culturally correct’, she is supported in this endeavour by her Azuo and her brother.

The novel ends with an optimistic vision for Uvi who would learn to accept the right kind of love and not look for the other kind; and a probable optimistic future for the ‘registered spinster’ narrator, Kevinuo who still thinks her to-be husband would arrive, even if he hobbles along with his walking stick.

The novel brings to the forefront the receded history of the Nagas. Kire successfully fleshes out the emotions of her characters, especially the trials and tribulations of the Naga women. She talks about the first Naga woman doctor, Khrielieu Kire, and how her achievement infused a spirit of encouragement amongst the young Naga girls.

Also read: Book Review: ‘Drawing The Line’ Zubaan’s Swanky New Graphic Novel

For a community whose history is much forgotten and marginalized, it is the onus of the community to preserve memories through photographs, objects, and memorials.

To aid the readers, Kire has ‘mapped’ Kohima as an epilogue. It is useful in understanding the context of the book at large.

A Respectable Woman redefines the nuances of respectability for women, in women, and by women, and is successful in making the silenced history heard.

About the author(s)

Sonakshi is currently pursuing her post graduation in English from Delhi University. A keen flaneur, she loves to read, and takes a keen interest in art and culture. She hopes to conquer world literature, and be a writer one day.