In an instance of positive discrimination, Delhi government recently has decided to provide for free metro and bus rides for women. Several women’s rights activists and feminists across the country have lauded the initiative as one that’s particularly emancipatory for lower middle class women. I take this opportunity to look for the forgotten histories of the women flaneur, draw instances from feminist literature and highlight contemporary feminist campaigns and art projects, built around women’s citizenship rights.

In India, women’s mobility is usually tied to her economic well-being. However, women’s access to women in the streets both enable and limit their citizenship rights. After Nirbhaya*, conversations around the citizenship rights of women made its way back into the public discussion. Feminist intervention around women’s safety in urban spaces and women’s right to experiencing the city led to the creation of various feminist campaigns in India. #IWillGoOut and #WhyLoiter, are offline and online campaigns documenting the idle walking of women in the streets in Indian urban and peri-urban spaces.

These campaigns are also responsible for making akeli-awara-azaad (alone-vagrant-free), a feminist anthem. Reclaiming the streets by engaging in a ‘risky’ behaviour of loitering comfortably in the streets, the campaigns seek to protest victim blaming prevalent in our patriarchal society. Commemorating ‘risky’ behaviour(s) condoned by women, such as, walking the streets, sleeping in public, being present in an ‘unsafe area’ in an ‘unsafe time’—various feminist campaigns have been built in the recent past. Take Back the Night, Meet to Sleep, Pinjra Tod are some of the most popular feminist campaigns working towards reclaiming various urban spaces (streets, parks, hostels) for women and increasing the presence of women in public.

Since 2003, Blank Noise, founded by artist Jasmeen Patheja, has been intervening in public spaces through art to generate agency in survivors, while dealing with sexual assault and gender-based violence. One of the projects, Museum of Street Weapon of Defence (2017), archived the ‘small acts’ women undertake every day in order to make the streets safer for themselves. The project depicted the ways in which an unspoken onus of creating a subject out of the vulnerable bodies of the women, perpetually rests on the shoulder of the women. In an attempt to acknowledge the complicity in the systemic oppression that give rise to biases while building solidarities, Blank Noise’s project “Talk to Me” attempted at bridging the gap between vulnerable bodies hailing from various spectrum of the caste-class-gender nexus.

In the recent past women’s behaviour in public has been policed by various right-wing outfits. For instance, in order to curb eve-teasing and stalking, vigilante groups known as Anti-Romeo Squads were set to work by UP’s CM Yogi Adityanath. These groups have been accused of harassing consensual couples and women in public. In fact, Indian politicians are well-known for policing women’s behaviour in the streets: banning mobile phones, eating chowmein, wearing jeans, you name it. However, this is not new to Indian culture.

Questions such as, “where do women go” and “how do they loiter” have plagued the men of Indian society for a long time now. For instance, around the second half of nineteenth century Bengal, a new category of educated women emerged from the zenana or antahpur (women’s quarters) of upper class Bengali households. This rise of the educated bhadramahila or gentlewomen coincided with their separation from the lower caste women, the proponents of Bengali popular culture. Among the women who had free access to the women’s quarter of a bourgeois Bengali household in 19th century Calcutta and surrounded areas, were the female barbers, sweepers, folk artists, singer, poets, dancers and maidservants (Banerjee, 1990).

The working women established a connection between the outer world and the gentlewomen of upper class households. Unlike their upper class counterparts, these women enjoyed the freedom of walking the streets of 19th Century Bengal and made a workplace out of it. Many rousing speeches and newspaper articles were published by the gentlemen of the era, in an attempt to drive these lower caste working women and artists out of the gentlewomen’s quarters while gentrifying the Bengali culture, freeing it from the clutches of these “vulgar” women (Banerjee, 1990).

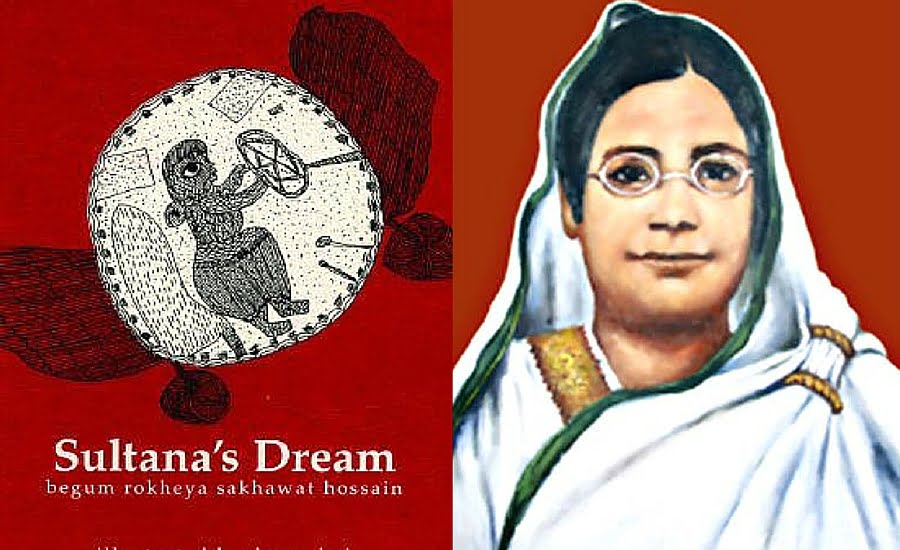

Amidst the changing role of women in the second half of 19th Century Bengal feminist educator, activist, writer, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain dreamt of an entire kingdom of safe space along with with a flaneuse heroine in her novella Sultana’s Dream, published in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine in 1908. In her sci-fi novella Sultana’s Dream, Rokeya Hossain caught a glimpse of her flaneuse heroine, Sultana, and her companion Sister Sara curiously walking through the utopian world of Ladyland. The men in this world have been put in the mardana (men’s quarters) in order to make the streets safer for women to walk comfortably. Rokeya imagined a world perfect for women to walk the streets without any interruption. She paints a utopia that has, in fact, been realised to some extent by certain groups of Indian women in contemporary Indian society.

Following the map of the past and Rokeya’s imagined world, we arrive at the ways in which the modern flaneuse walk the streets. In recent times, various feminist campaigns and art interventions have been created specifically to celebrate and empower women’s presence in public. Goa-based artist Afrah Shafiq, drawing inspiration from the novella, has re-imagined the sisterhood forged within the walls of the zenana and women’s relationship with books during the colonial era in her project Enter Sultana’s Reality. Shafiq’s animated project coupling anecdotal histories of revolutionary (yet forgotten) women with images found in the archives of Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, brings to mind the nature of contemporary feminist activism that seeks to strike a balance between the analogue and digital, online and offline, technological and material.

Campaigns such as ‘Meet to Sleep’ by Blank Noise and #TakeBacktheNight get women together to enjoy their own company and re-occupy the public spaces as women who dare to simply be.

Women’s presence in the streets has been weaponised as a mode of resistance against rampant street harassment and everyday sexism, by various feminist collectives. Campaigns such as ‘Meet to Sleep’ by Blank Noise and #TakeBacktheNight get women together to enjoy their own company and re-occupy the public spaces as women who dare to simply be.

Also read: Why Loiter? Book Review: Imagining Our Streets Full Of Women

While looking for the female flaneur in literature and history Lauren Elkin, in her book, Flaneuse, Women Waking The City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London, follows the word “flaneur” around the many literatures and contexts it has arisen within Europe. On her way, she invents the word flaneuse, a feminine form of the masculine noun ‘flaneur’. Elkin takes us through a brief history of the flaneur’s appearance and disappearances in the pages of European literature and history. She tells us, the more the flaneur is made to appear, the more they have evaded; sometimes as a figment of the imagination, sometimes as a ‘mythological or allegorical figure.’ A flaneuse herself, Rokeya Hossain wrote of her flanerie in her letters.

A woman flaneur in India will remain a fictional character and an invisible subject for as long as the streets are unsafe for women to loiter. Urban planning will have to take into account gender inequality while designing new spaces. New modes of contemporary feminist activism built around the citizenship rights of Indian women, to an extent, has captured Rokeya’s vision of a feminist utopia: a phantasmic akeli-awara-azaad (alone-vagrant-free) woman reclaiming the streets, dwelling in the pleasure of just walking and curiously idling away with her companion.

*I choose this name in an attempt to avoid the graphic description that generally accompanies the incident resulting in triggers amongst survivors of SH.

Also read: 6 Times Desi Women Reclaimed Public Spaces As Their Own

References

‘Marginalisation of Women’s Popular Culture in Bengal‘ in Recasting Women, by Sumanta Banerjee.

Debarati is pursuing MPhil in Women’s Studies. She is most likely to be found making people remember that feminism is inherently anticapitalist and antifascist. You can follow her on Twitter.

Featured Image Source: QRIUS