Smriti Bhoker is an Urdu poet who is currently pursuing a masters degree in sociology from Delhi. Urdu, as Smriti herself calls, is a “dying language”. Besides the annual visits to Rekhta fests, I too have massively failed to engage with Urdu’s world of expressions—be it sadness, happiness, love or resistance—and its varied forms like poetry, ghazals, shayari or stories. However, despite our collective ignorance of the language’s power and poise, we still manage to learn a few of its words; thanks to Bollywood and its fetishising tendencies.

However, for people like Smriti, who do not simply learn, speak, read or write in Urdu, but also express and live through the language, the approach is not limited to song lyrics or dialogues from pop-culture. For them, the horizon is ever expanding, where they themselves are a very crucial part of its evolution.

Her Urdu satires reflect the current deplorable socio-political scenario of the country—the religious hatred, the patriarchal society and the obscurity of freedom—all packed together in her pieces. They give you a reality check—one that you are already, sub-consciously aware of, but you fail to ponder over in your everyday. These stories are narrated with a distinct style of oration, which make them even more appealing.

In conversation with Smriti Bhoker, about her journey with the Urdu language, and its future.

The love ran out, and thankfully satire doesn’t need a lot of love. Satire needs unadulterated bitterness and that’s an equally motivating drive.

When and why did you start reading and writing in Urdu?

Smriti Bhoker: I used to write English poetry in school and I was beginning to take it seriously in my second year of graduation when my father suggested me to translate some of my work for him. According to him, since my upbringing was done in a house where 4-5 languages were spoken, he felt my hold of Urdu and Hindi would naturally be better than English and he was right! Both my parents were avid reader of Urdu literature and Panjabi folk, qawwali and ghazals were my household’s background music. For the longest time, I have tried to run away from my own languages. When I developed an interest in Urdu literature, my dad told me about a few poems he wrote when he was young, one of them about my mother when he was away for training. My father who is now in the army, tells me that he wanted to be a poet when he was young; he just didn’t have the luxury of a family that would support him on it, or the money to afford the life of a writer. As a result of this, the support for my work at home has been radical.

Who or what inspired you to indulge in this field of Urdu satires? What are the ways through which the gender question appear in your writing as well as in the domain of Urdu satires?

Smriti Bhoker: Poetry needs a ridiculous amount of love. For about two years, I only wrote poetry. While doing that, I had started to educate myself on social issues as I was following the lead of Faiz, Jalib and Paash. The love that is foundational for any kind of poetry to come forth died, the reason being the current times we are living in. Even my book that comes out this year, which is a collection of resistance poetry, has very few ghazals that were written post 2017. The love ran out, and thankfully satire doesn’t need a lot of love. Satire needs unadulterated bitterness and that’s an equally motivating drive.

My answer for the second part of the question is that I was a feminist before I started writing. So naturally one of the questions that one would ask while indulging in Urdu literature is that why doesn’t it have enough women writers? The ones it does have either come from extremely privileged backgrounds or extremely disturbed ones. I saw my poetry was still accepted to some extent but my politics is where I saw a lot eyes rolling. This is something you would notice in the prestigious Urdu literature circles as well—my satires usually cover gender-politics not because it interests me or because it agitates my conservative relatives (I mean those reasons are tempting enough) but I primarily cover them because here isn’t enough material on it in the form of satire by women.

my satires usually cover gender-politics not because it interests me or because it agitates my conservative relatives (I mean those reasons are tempting enough) but I primarily cover them because here isn’t enough material on it in the form of satire by women.

Do you see yourself continue in this field, in future? Do you plan to translate it into a more professional field of interest?

SB: I’m hoping to continue in this field, not just as a satirist and a poet but eventually a playwright and scriptwriter too. I plan to write on Urdu and Punjabi literature academically as well. For now, I would like to read more and learn Bengali.

Also read: Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: His Qawwali And Everyday Sexism

The oration of your satires demand a certain set of skills. Where did you learn them and what can you tell us about its importance in presentation of satires?

SB: There is a brilliant voice artist by the name of Fawad Khan who covers Manto’s essays and Chugati’s stories. He makes Manto’s work sound better than any voice artist I have ever heard and I have heard him recite a lot of Manto. It’s interesting that there is not much about him that I know except that he used to live in Pakistan. Yet everything I know about oration comes from him or from Zia Mohiuddin’s collected recitals. I do this exercise where I hear what my satire would sound like if Fawad Khan had read them. Then I read them like Zia Mohiuddin would. After these two exercises, I read them as Smriti would read them.

Since a lot of people do not prefer reading anymore it’s good to know how to present your work. However, I still believe we should try to go for authentic writers as opposed to those who know how to orate their work effectively.

If there is someone reading this now and wants to get involved in this field, what all suggestions do you want to give them?

SM: READ, read Urdu as much as you can. It’s a dying language and what’s left of it was claimed by Karan Johar’s idea of Saba who is the pop culture reference for what Urdu women writers should look like. Pop culture also makes this language look like an accessory for the urban elite when it’s historically one of the greatest weapon used against them. Make sure your foundation comes from the Urdu that used to inspire and provoke thought.

Also read: Rekhti: The Lost Genre Of Urdu Feminist Poetry

Lastly, tell us about your bitter-sweet journey with this field.

SM: There is a dilemma that I have lived in, ever since I started out. I have been as hopeful as the promise of a better tomorrow in the eyes of a drunk student who has just discovered Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s resistance poetry and as hopeless as the drunk professor’s faith in the system who has to teach this poetry in the morning. My journey is me in the place of the student some nights, and some nights the professor. Since election, sometimes it’s both. I started out as a fangirl of Gulzar thinking Urdu starts and ends at Khushboo and now I cannot conceive a form of revolution that isn’t the embodiment of this language. With that I am also ready to write a satire on why this imagined revolution will fail.

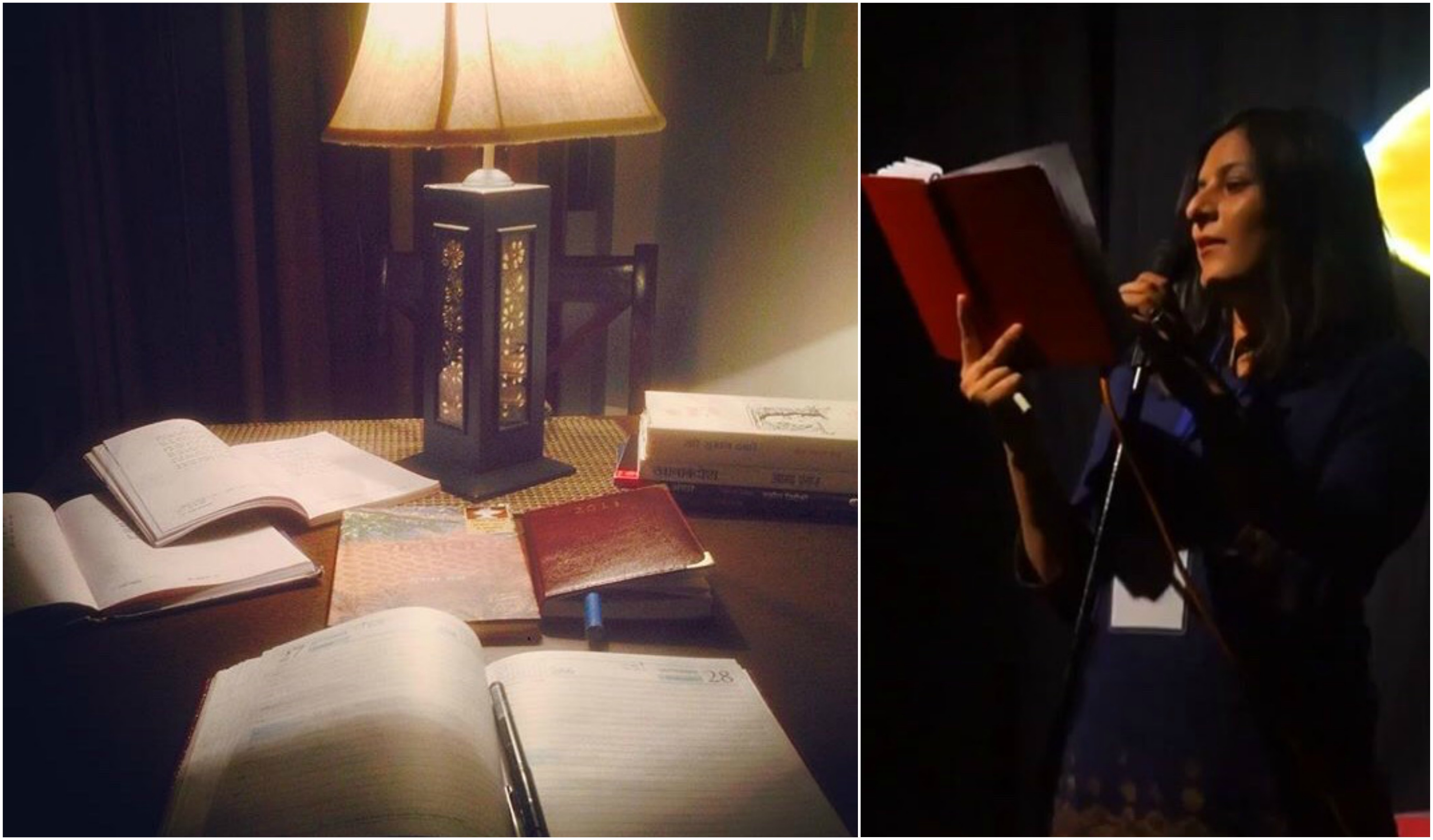

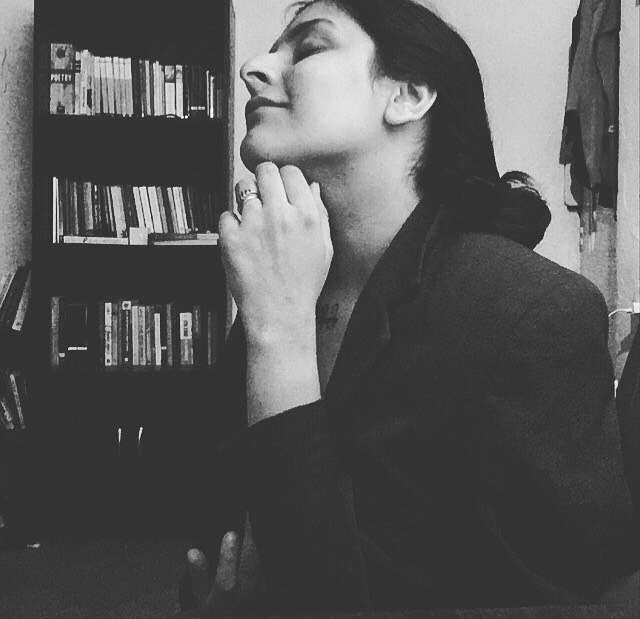

All pictures are provided by Smriti Bhoker. You can find her on Sound Cloud, Instagram and Facebook.

About the author(s)

Pragya is a Master's Graduate in Sociology from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She works as the content editor at Feminism In India. She is also a ramen enthusiast, a hummus mother, a postcard hoarder and a wannabe cat lady. She still prefers writing on her notebooks, rather than on her laptop, but her job demands her to do just the opposite. Her favourite season is spring, and her alter ego is that of Mrs. Dalloway who said, "She would buy the flowers herself", in case no man ever buys her any!