Benjamin Law’s book Gaysia is an absorbing read filled with quirky humour and informative facts about the diverse queer culture in Southeast Asia. An Australian child of Chinese immigrants, Law ventures into seven Asian countries to find out about the attitude towards the queerness of the world’s largest continent. In his very own words, “For me, it was time to go back to my homelands, to reach out to my fellow Gaysians: the Homolaysians, Bimese, Laosbians and Shangdykes.” In his book, Law proves himself as a highly effective investigator and an empathetic reporter. He presents his readers a candid description of societies that are struggling, yet slowly accepting its different sexual identities.

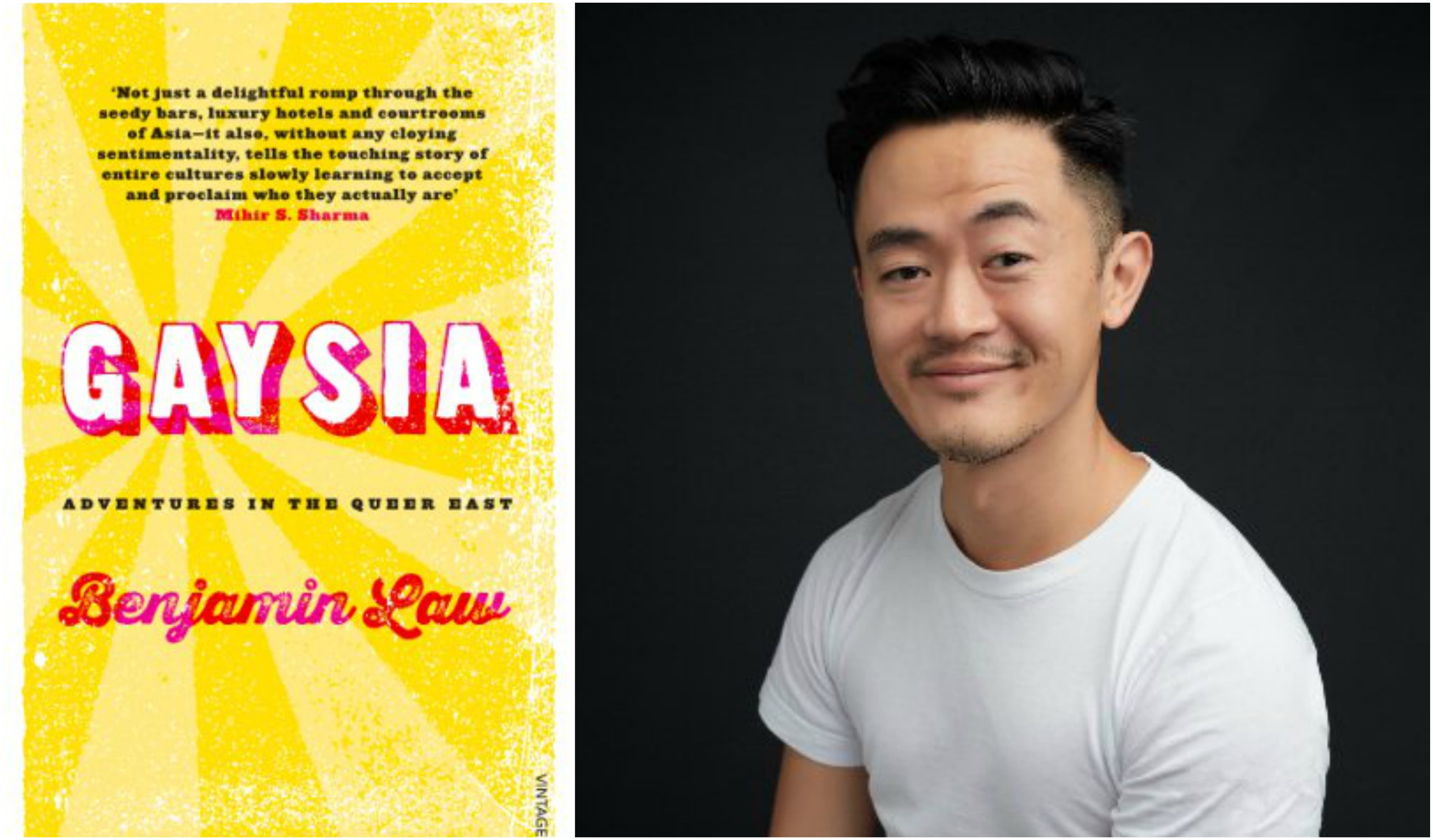

Gaysia: Adventures In The Queer East 2012

Author: Benjamin Law

Publisher: Random House India

Genre: Non-fiction

The author begins his book with the claim that of all the continents, Asia is the gayest. He reasons this out by stating that, since seven of the most populous countries are situated in Asia, it is then common sense to say that most of the world’s queer people live in Asia.

Unfortunately, Asia also happens to be the most queerphobic of all the continents. The norm of heteronormativity has always towered above the desires of LGBTQIA+ community. There is a haunting silence on the queer people’s issues in the continent—not only are they not spoken about but are invisibilised altogether.

In his book, Law proves himself as a highly effective investigator and an empathetic reporter. He presents his readers a candid description of societies that are struggling, yet slowly accepting its different sexual identities.

For me, it was a heartfelt experience to see a white author utilise his privilege to disrupt the silence over Queer issues. Law acknowledges his white gay privilege—he knows that he is lucky to be born in a part of the world where he can hold hands with his boyfriend in public and can influence the government to recognise same-sex marriages. He knows that it’s not the same case with his Queer fellows in Asia. So he decides to fulfil his allyship by passing on the microphone and reporting the experiences of his fellow Queers as compassionately as possible.

I found the book engaging down to the last page. Law strikes the right balance between thought-provoking and hilarious. His tongue in cheek commentary is sure to give you the giggles and marvel at his wit. He loves to play on words and uses his humour to deal with the cultural shocks that he receives on his travels. Law is observant of the eccentricities of the different places he travels to, and even good-naturedly makes fun of it. Be it middle-aged women farting midst yoga sessions or his graphic description of his digestive troubles in India, his comic timing is perfect.

Law’s immersive style of story telling is his greatest strength as a writer. Gaysia is a blend of solid research and adventure. The author is curious, open-minded and approaches the lives of his subjects with a kind eye. He takes his readers on a journey to meet moneyboys in exclusive gay resorts of Bali, transsexual beauty pageants in Thailand, gay-lesbian sham marriages in China, fierce celebrity drag queens in Tokyo, gays and lesbians going through conversion therapy in Malaysia, HIV affected patients in Myanmar and anti-LGBT spiritual gurus in India.

Though I truly enjoyed the book, I really wish Law had given a short epilogue to his readers on what his travel endeavours in the Queer East meant to him personally. The book ends with Law having his first ever Pride parade in Mumbai, but the readers are left without a sense of closure.

Also read: Book Review: Work Like A Woman: A Manifesto For Change By Mary Portas

As one reads further, we get an insight into different levels of oppression and marginalisation of Queer community across different countries. Law interviews and gets perspective from people from all walks of life. In the section on China, we are told about self-flagellation as a behavioral technique prescribed by psychologists to change the sexual orientation of its people. Homosexuality is seen as either a mental disorder that can be cured or something equivalent to a ghost.

Similarly, we are also given the account of attitudes towards homosexuality in Malaysia, where reiterating verses of Quran is thought of as an ultimate way of redeeming oneself from homosexuality. Law also introduces us to a famous spiritual guru in India (not very hard to guess), who claims to have reversed homosexuality in people with pranayama yoga.

Law doesn’t give his readers just one view of Queer lives but gives us the details from different angles and brings out complexities of being a Queer in Asia. In Gaysia, we are given a look at modern Japanese society that likes to watch its Queer community on television but not so much in real life. While transgenders and transsexuals are being slowly accepted in Japan, there is zero tolerance when it comes to lesbians.

Law acknowledges his white gay privilege—he knows that he is lucky to be born in a part of the world where he can hold hands with his boyfriend in public and can influence the government to recognise same-sex marriages.

The author also presents to us fascinating stories of resistance against the heteronormative ideals. We are told about the increasingly popular practice of sham-marriages in China, where young gay men and lesbian women marry each other to escape the pressures from their conservative families. Law also encounters the gay royal prince in India who happens to be the first openly gay prince in the world.

Overall, Gaysia is a personable and a moving exploration of cultures that are slowly but steadily accepting its queer communities. The book is highly recommended to anyone who wants to acquaint themselves to queer cultures other than their own.

Also read: Book Review: Cyber Sexy: Rethinking Pornography By Richa Kaul Padte

About the author(s)

An English literature graduate who likes to learn different art forms and wishes to create a social impact.